views

With the curve flattening in cities such as Delhi and Mumbai, it is giving a false comfort of Covid-19 fading away. The reality is that the second wave is shifting fast and upwards to the other regions, more so in rural India, where it is not being tracked or traced. I have written about it here and here.

We see awareness among state governments rising. I could sense the urgency when I spoke with the health ministers of Punjab and Haryana. As part of CIPP work in managing and helping the Covid relief process in rural areas, I have spoken to numerous District Commissioners and front line staff across multiple districts and states.

Some common elements and granular details are emerging now, as rural and small-town India battle the second wave of Covid-19.

Glaring rural-urban gap

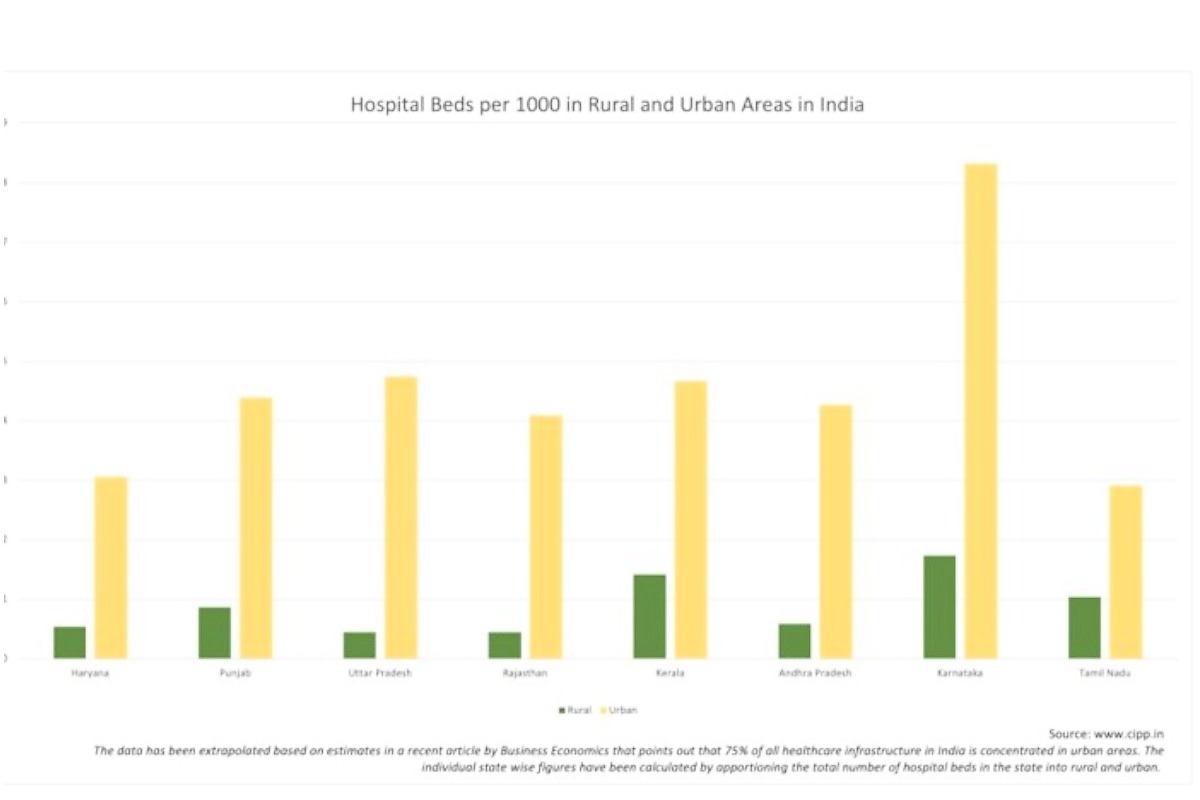

The huge, ever-widening urban-rural chasm in healthcare services, which was obvious to any interested observer, has found its denouement with Covid. Over the last many decades, besides the puny investment in rural healthcare services, the availability too has been largely non-existent. Public sector investment in healthcare service is poor in both quantity and quality, while the private sector provides 75% of its services to 25% of the urban population. That leaves the rural population as well as the urban poor exposed. Investments by governments in primary health centres (PHC), community healthcare centres and district-level general hospitals have awning gaps: shortage of doctors, para medical staff, ambulances and basic medical equipment, including oxygen plants.

Medical staff do not want to live or work in rural areas. The more backward the district, the lesser the chance that it will have staff in the government facilities. These gaps and problems have been ignored as politicians have rarely won elections because of good health facilities. But the pandemic is showing they almost certainly risk losing an election because of poor healthcare facilities.

The biggest fear was always: what would happen if the Covid virus reached rural India? Now that it has got into the rural areas, what do we do?

Different governments are reacting to this challenge in different ways. Healthcare infrastructure cannot be built overnight and doctors or trained staff cannot be motivated to go to Covid-infested rural areas.

Haryana has formed 8,000 teams to visit villages and carry out testing, tracking and tracing of the Sars-CoV-2 virus that causes Covid-19. Punjab has also formed teams for rural services. States are trying to marshal all the manpower that can be diverted to rural areas.

To allay the fears of medical personnel, they all have to be vaccinated before being sent to rural areas. Second, their life and health insurances have to be increased by the state government. Third, they have to be given a hardship allowance for their rural service. These three steps are absolutely necessary for any rural anti-Covid drive to succeed.

Panchayats and blocks

There is enormous testing and vaccination hesitancy in rural areas. People do not want to accept that they are suffering from Covid, lulling themselves into believing that their ailments are anything else but Covid. Concerns are aplenty about the safety of the vaccine. Fear, combined with ignorance and misinformation, is creating testing hesitancy; besides, when rural citizens do summon the courage, it is difficult to get tested in the villages. State governments are making efforts to reach rural areas but these will never be sufficient. Hence, it is important that a parallel and lateral approach be adopted for rural areas.

It is important for rural citizens to have oximeters and thermometers available as well. They should be taught about the three levels of Covid: mild, moderate and severe. Asha workers and the anganwadi workers are closer to the frontlines. They will be able to learn quickly about these three levels. If equipped with basic kits and knowledge they will save more lives than any district-level hospital.

The testing labs are mostly in the cities; transporting samples from the rural areas to the lab for testing is going to be a long haul. Already, in cities, it is taking 48-72 hours to process the test samples. This is too long for severely ill Covid patients as the deterioration is very rapid in such cases. These are the cases that need urgent hospitalisation, oxygen and ventilators.

Moderate cases have to be prevented from turning into severe, and mild cases need quarantine to control the spread.

These are problems that do not solve well at scale as they are wicked, distributed problems with multiple critical factors involving logistics, people and training. Therefore, it is also important that freedom and support to decentralisation be provided right down to the panchayat level.

If a panchayat wants to take a decision to lock down a village, it should be allowed to do so as long as it follows the standard operating procedure, and does not disrupt essential supply chains.

Recognising what decisions can be taken at the ground level and what cannot be taken is a crucial element. In my conversation with the health ministers of Punjab and Haryana, I have noticed the wide variance in how each state is organising itself in preparing for the imminent rural Covid wave.

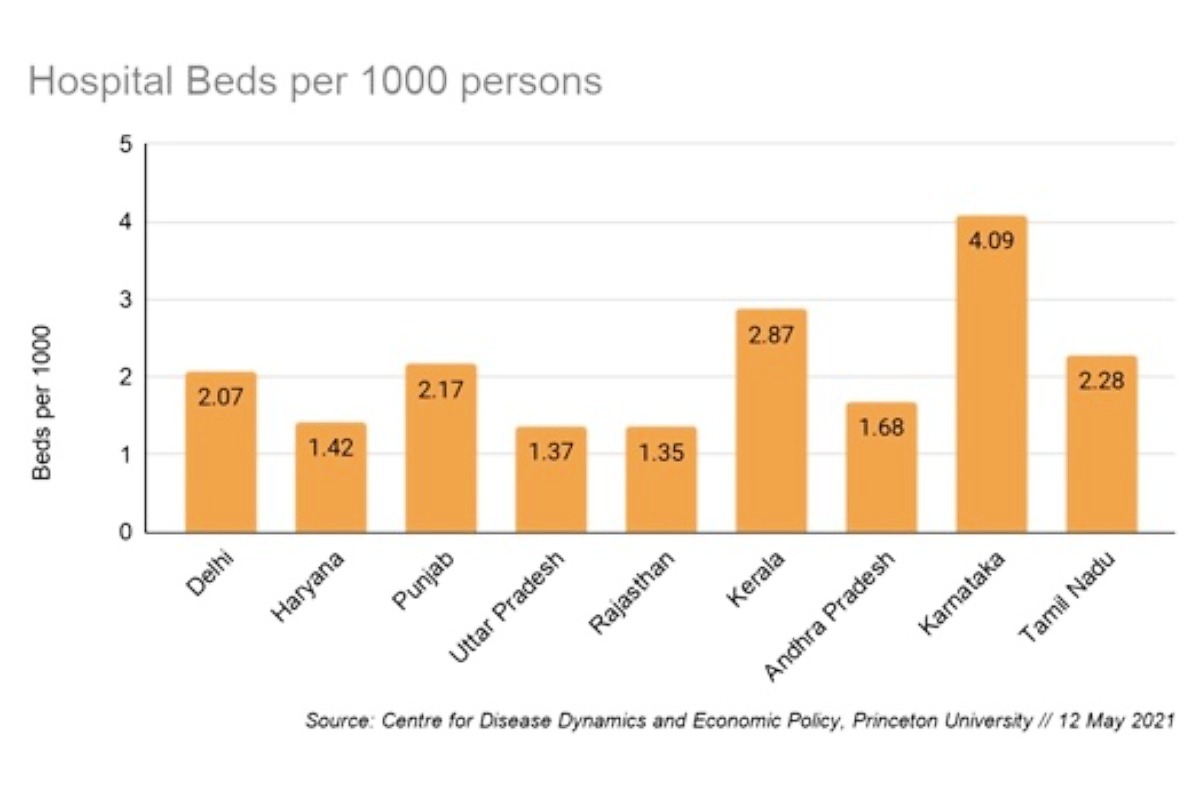

Punjab has a better ratio of hospitals and beds than Haryana; its health minister Balbir Singh Sidhu is also well aware of the need for healthcare services. Even before the second wave began, he had started investing in building large hospitals in the state, each with more than 1,000 beds. Punjab also has several other large hospitals in Jalandhar, Amritsar and Ludhiana thanks to the influx of NRI populations coming for treatment to the state. Haryana does not have many large hospitals, except for one in Gurgaon and an AIIMS in Rohtak.

The lack of large hospitals in the private sector is due to several factors, including the high risk-low return perception that prevents entrepreneurs from investing at scale in a single location. This severely restricts their ability to meet the needs of the country during a pandemic.

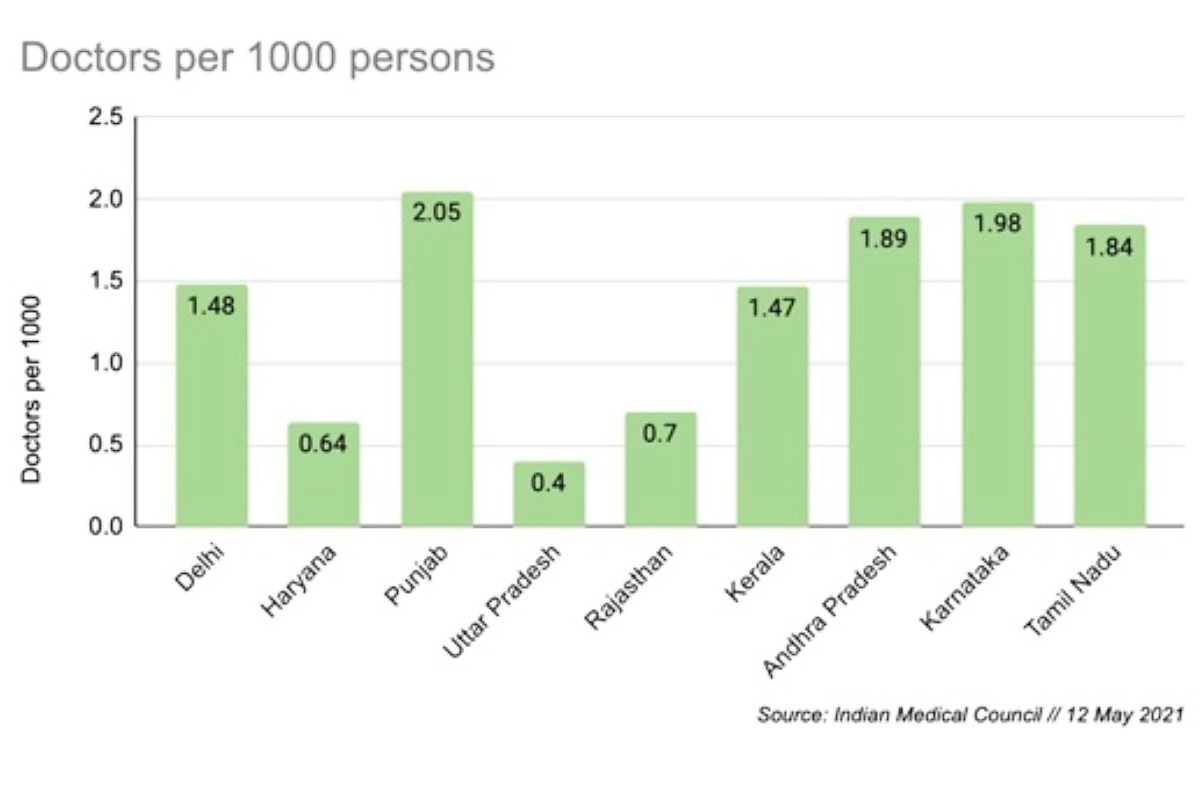

Public sector investment in healthcare care services has been anaemic for decades; only the AIIMS has any scale. Most general hospitals at district levels do not possess top quality infrastructure or personnel, and face low investment in critical infrastructure such as on-premise oxygen generating plants. But, more importantly, it is the lack of doctors, para-medical or lab technicians in public sector hospitals. While the exact figures are not easily available for each and every state, the overall number of doctors per thousand combined shows the poor capacity of trained staff.

Populous states such as Uttar Pradesh are particularly low down the scale and fare worst, as is showing up in the death numbers in the state. Hence, while the second wave might ebb in cities, the jumbo Covid centres that are being created there should service the rural population. An ambulance-based logistics chain needs to be set up between rural and urban hospitals.

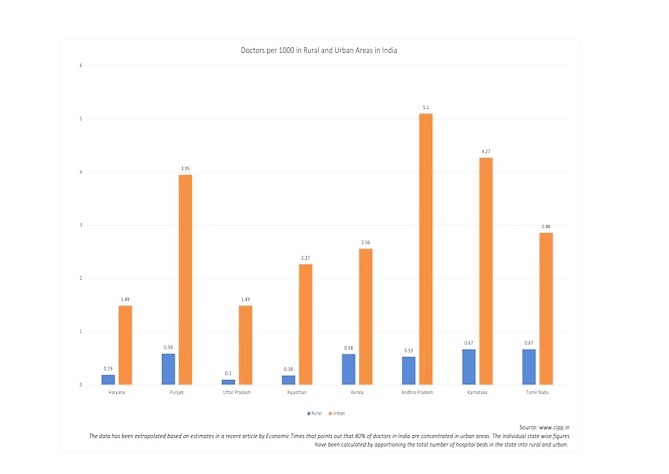

More important is the difference between the rural and urban areas in terms of the distribution of doctors. The paucity of doctors and healthcare services in rural areas is well known.

I have written several times about the rural areas approach. Dividing doctors’ numbers on a simple 80:20 division in rural and urban areas shows the wide variance in Chart 3 below.

There are anecdotal reports of the lack of doctors, nurses and anaesthesiologists across small town India. Ventilators cannot be used without anaesthesia and are useless as a life-saving equipment in an ICU without a trained anaesthesiologist. Now, the skill of injecting an anaesthesia, or the quantity that needs to be injected, can be taught, but the medical-legal requirements insist that an anaesthesiologist can only do it.

The multi-pronged approach for rural areas involves devolution of resource depots at block level. These resource depots have to be critical equipment, with oxygen cylinders being the primary. Portable oxygenators are crucial for controlling level 2 moderate patients from deteriorating to level 3. Logistics for transporting level 3 patients to nearby hospitals from the village will be the most important part of saving lives because of the distance between hospitals and the shortage of the number of beds in rural hospitals. Finally, these patients will have to be brought to cities, especially the new Covid centres being created. Even though the Covid wave may be ebbing away in the cities, we should not stop creating additional beds with oxygen — these will be needed very soon.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Telegram.

Comments

0 comment