views

Recognizing the Symptoms and Calling for Help

Understand that sometimes there are very subtle or no warning signs. Some heart attacks are sudden and intense and provide no warning signs or tell-tale symptoms. However, in most cases, there are at least subtle clues that usually get rationalized or marginalized. Early warning signs of heart disease include high blood pressure, sensation of chronic heartburn, reduced cardiovascular fitness, and a vague feeling of malaise or being unwell. These symptoms may start many days or weeks before the heart muscle gets damaged enough to become dysfunctional. Symptoms in women are particularly hard to recognize and are ignored or missed even more often. Major risk factors for heart disease, heart attack, and stroke include: high blood cholesterol levels, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, cigarette smoking and advancing age (65 years and older). A heart attack doesn't always lead to cardiac arrest (complete heart stoppage), but cardiac arrest is always indicative of a heart attack.

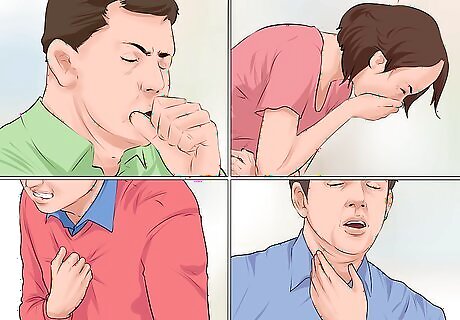

Recognize the most common symptoms of a heart attack. Most heart attacks do not occur suddenly or "out of the blue." Instead, they typically start slowly with mild chest pain or discomfort that builds over many hours or even days. The chest pain (often described as intense pressure, squeezing or achiness) is located in the center of the chest and can be constant or intermittent. Other common symptoms of a heart attack include: shortness of breath, cold sweats (with pale or ashen skin), dizziness or lightheadedness, moderate-to-severe fatigue, nausea, abdominal pain and a sensation of severe indigestion. Not all people who experience heart attacks have the same symptoms or the same severity of symptoms — there's lots of variability. Some people also report feeling a sense of "doom" or "impending death" that is unique to the heart attack experience. Most people experiencing a heart attack (even a mild one) will collapse to the ground, or at least fall against something for support. Other common causes of chest pain don't typically lead to sudden collapse.

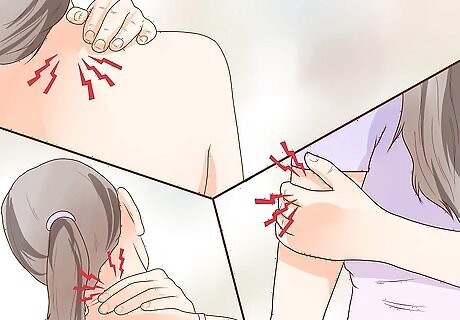

Recognize some of the less common symptoms of a heart attack. In addition to the tell-tale symptoms of chest pain, shortness of breath, and cold sweats, there are some less common symptoms characteristic of myocardial infarction that you should be familiar with in order to better gauge the probability of heart failure. These symptoms include pain or discomfort in other areas of the body, such as the left arm (or sometimes both), mid-back (thoracic spine), front of the neck and/or lower jaw. Women are more likely than men to experience less common symptoms of heart attack, particularly mid-back pain, jaw pain, and nausea/vomiting. Other diseases and conditions can mimic some of the symptoms of heart attack, but the more signs and symptoms you experience, the greater the likelihood your heart is the cause.

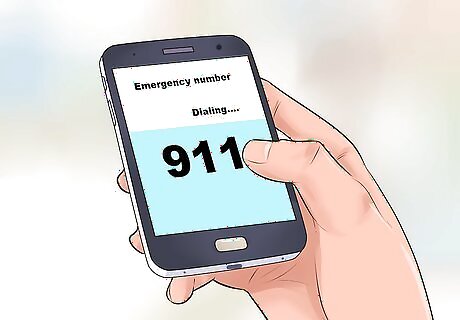

Call emergency services immediately. Act immediately and call 9-1-1 or other emergency services in your area if you suspect someone is having a heart attack. Even if they don't display all or even the majority of the signs and symptoms, calling for medical help is the most important action you can take for someone in severe distress. Emergency medical services (EMS) can begin treatment as soon as they arrive and are trained to revive someone whose heart has completely stopped. If you can't call 9-1-1 for some reason, ask a bystander to call and give you updates as to the estimated arrival of emergency services. Patients with chest pain and suspected heart attack who arrive by ambulance usually receive faster attention and treatment at hospitals.

Treating Before Medical Help Arrives

Put the person in a seated position, with knees raised. Most medical authorities recommend sitting a suspected heart attack sufferer down in the "W position" — semi-recumbent (sitting up at about 75 degrees to the ground) with knees bent. The person's back should be supported, perhaps with some pillows if at home or against a tree if outside. Once the person is in the W position, then loosen any loose clothing around his neck and chest (such as his necktie, scarf, or top buttons of his shirt) and try to keep him still and calm. You may not know what's causing his discomfort, but you can reassure him that medical help is on its way and that you'll stay with him at least until that point. The person should not be allowed to walk around. Keeping a person calm while having a heart attack is certainly a challenge, but avoid being too chatty and asking lots of irrelevant personal questions. The effort required to answer your questions may be too taxing to the person. While waiting for emergency help, keep the patient warm by covering him with a blanket or jacket.

Ask the person if she carries nitroglycerine. People with a history of heart problems and angina (chest and arm pain from heart disease) are often prescribed nitroglycerine, which is a powerful vasodilator that causes large blood vessels to relax (dilate) so more oxygenated blood can reach the heart. Nitroglycerine also reduces the painful symptoms of a heart attack. People often carry their nitroglycerin with them, so ask if that's the case and then assist the person in taking it while waiting for emergency personnel to arrive. Nitroglycerin is available as little pills or a pump spray, both of which are administered under the tongue (sublingually). The spray (Nitrolingual) reportedly is faster acting because it's absorbed quicker than the pills. If unsure of the dosage, administer one nitroglycerine pill or two pumps of the spray under the tongue. After administration of nitroglycerine, the person may become dizzy, lightheaded, or faint soon after, so make sure she is secured, sitting down, and not in danger of falling and hitting her head.

Administer some aspirin. If you or the heart attack sufferer has any aspirin, then administer it if there's no indication of allergy. Ask the person if he has an allergy and look for any medical bracelets on his wrists if he has trouble talking. Provided he is not younger than 18 years old, give him a 300 mg aspirin tablet to chew slowly. Aspirin is a type of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) that can reduce heart damage by "thinning" the blood, which means preventing it from clotting. Aspirin also reduces associated inflammation and helps reduce the pain of a heart attack. Chewing the aspirin allows the body to absorb it faster. Aspirin can be taken concurrently with nitroglycerine. A dose of 300 mg is either one adult tablet or two to four baby aspirins. Once at the hospital, stronger vasodilating, "clot-busting," anti-platelet and/or pain-relieving (morphine-based) drugs are given to people experiencing heart attacks.

Initiate CPR if the person stops breathing. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) involves chest compressions in order to help push some blood through the arteries (especially to the brain) combined with rescue breathing (mouth to mouth), which provides some oxygen to the lungs. Keep in mind that CPR has its limitations and doesn't usually trigger a heart to start beating again, but it can provide some precious oxygen to the brain and buy some time before emergency services arrive with their electrical defibrillators. Regardless, take a CPR class and at least learn the basics. When someone starts CPR before emergency support arrives, people have a better chance of surviving a heart attack or stroke. People not trained in CPR should only do chest compressions and avoid rescue breathing. If the person doesn't know how to effectively deliver rescue breathing, they will simply be wasting time and energy by improperly administering breaths that are not effective. Keep in mind that time is very important when an unconscious person stops breathing. Permanent brain damage begins after four to six minutes without getting oxygen, and death can occur as soon as four to six minutes after enough tissue is destroyed.

Comments

0 comment