views

Meerut/Lucknow/Mau: The 57-odd years that Ram Manohar Lohia lived in this world, every move he made was aimed at one grand outcome: to unshackle the masses from the caste system and free up their creativity. Ironic then that his followers in Uttar Pradesh have been betting their political fortunes on a continuation of the caste kinship to shepherd them into voting their caste.

He would have, for instance, approved of the cracks in the high wall of caste in this heartland of all heartlands, a trend seen never before. It's a change no one can claim credit for. The transformation seems to be a result of a variety of converging factors: the mainstreaming of technology; aspirations, a paradox, given that it coexists with abject hopelessness; an almost permanent state of crisis in agriculture; growing irrelevance of caste-based traditional occupations; and the rise of the educated unemployed.

It could well be this trend that hacks crisscrossing the state from Ghaziabad to Ghazipur and Bahraich to Banda seem to capture when they shoot from the hip terms like non-Yadav OBC consolidation, fractured Muslim vote, and reverse polarisation.

Mohammed Afzal, far removed from the Twitter feed of New Delhi media, will help you make sense of all this in simple words. He is one among the 3.2 million artisans employed in Badohi – just 45 km from Varanasi – that probably is the world’s largest hand-woven carpet hub. Afzal is pained that since he is a Muslim everyone assumes which way he will vote.

“Hum mazdoor hain roz kuan khodte hain, roz paani peete hain. Hum bunkaar hain yahi sochenge aage koi rozgar aaye. Isliye nahin denge vote ki hum musalman hain. (I am a weaver, I survive on a day to day basis. My vote is for someone who will give me employment and it’s above my religious identity),” he says.

The paradox of caste and religion is further highlighted just a few yards away in another weaver cluster. Lal Bahadur Maurya has been working here for several years and claims the occupation of being a carpet weaver unites all the fellow workers irrespective of their caste. “Kaleen hum sabko jodta hai, har biradri ke log hain yahan, Koeri, Kurmi, Harijan, Yadav, hum Maurya, bhed chaal hai, jahan lehar ghoom gaya hum chale gaye, 2014 mein BJP ke saath the (We are like cattle, all of us work together and in whichever direction the electoral wind will blow we will go and support that party. In 2014 we voted for BJP),” he says.

But, the topic being caste, don’t expect that hypothesis to go unchallenged.

“It’s just a coincidence that caste and class overlap among the lower OBCs. Lohar, sonar, kumhar, kewat and other non-yadav OBCs may be voting for BJP not just because of occupational category,” he says, asserting that caste continues to be the great mobiliser.

Kumar observes that for OBCs the BJP is a natural transition. The party has been trying to tap into the simmering discontent among the non-Yadav OBCs who complain that the upper layers among the OBCs have been the biggest beneficiaries of reservation.

Naveen Kumar, like his ancestors, is a barber. This first-time voter in Rasoolabad reserved constituency, where BSP strategist Naseemuddin Siddiqui’s son Afzal Siddiqui is seeking mandate, is clear about his choice. “Modi said he will give me job. I am waiting for him to deliver on his promise, and I know he will. If he can carry out an attack on Pakistan, he can do that as well,” Kumar says.

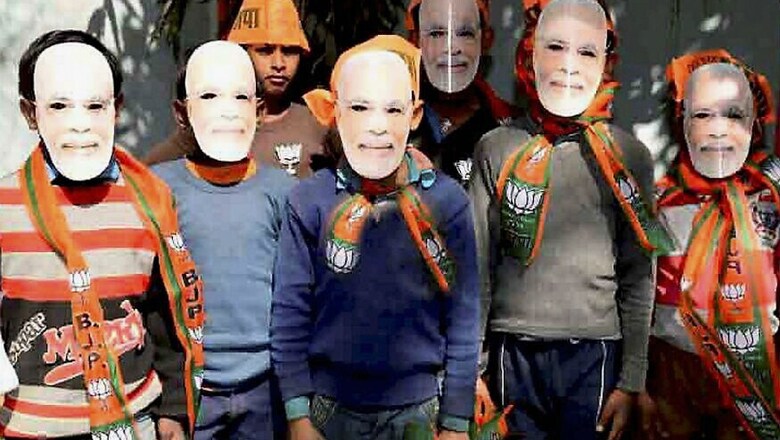

Once again, the votes of this new “class” are not for BJP, it’s for PM Modi.

“Modiji bole hain to hoga, ameer ko hamare saath khada kar diye note bandi se (If Modi has said then it will happen, he made the rich stand with us in queues because of demonetisation),” says one of them.

Else, just why would any politician rake up Harvard University in Maharajganj, an apology of a district with a literacy rate of 63%?

Yet Modi did. “Desh ke kisano ne dikha diya hai, desh ke mazdooron ne dikha diya hai, desh ke imandaron ne dikha diya hai, Harvard se zyada dum hota hai hardwork mein. (The farmers have shown, the labourers have shown, honest people of this country has shown… That hard work is mightier than Harvard,” he roared, the crowd erupting.

Modi made those remarks in the context of demonetisation. The crowd assembled may not have heard of Harvard or Amartya Sen, but it all translated to them as a great leader speaking in their language that the sweat of their brow was more powerful than a condescending nod from the elite.

Social scientist Manisha Priyam adds another angle to the parachuting in of Harvard in Maharajganj. “Modi is referring to the educated unemployed class. It’s an appeal to the Brahmin class – not to the religious pundits – but to a new class that has been through the mofussil colleges but have nowhere to go.” Priyam calls them ‘Sawarna Poor', the educated class of youth who complain against reservations.

In 2012, Samajwadi Party had won 85 out of 150 seats in Purvanchal and Akhilesh Yadav had appealed to this class of youth. Post his victory, Akhilesh had flooded this region with employment exchanges. Such is the aspirational quotient that Eastern UP is one of the biggest market for the Oxford University press school text books.

Priyam points out that Varanasi’s famous Sunbeam School has 16 branches in this region, with an enrollment of 25,000.

The reference to the honest average hard working Indian who doesn’t shy away from “giving up” his gas subsidy for the greater common good is what Modi’s new narrative will increasingly be.

Brijesh Kumar Gupta, a third generation businessman, is one such. He strongly objects to any obvious association of his caste identity with his voting preference. “Baniya shabd khatam kariye, ab koi nahin hai baniya, jo business kar raha hai sab baniya ha, aur sab BJP ke saath nahin hain, Akhilesh Yadav ne expo mart banaya hai. (Stop this blanket usage of the word Baniya. Today, anyone who runs a business is a baniya. And don’t assume all of them are with BJP. Akhilesh, for instance has created an expo mart here),” he says.

The new Indian doesn’t shy away from picking up a broom for swachh bharat to bearing a temporary pain and standing in queues for his own money. Whether it is this emerging class-consciousness that’s generating an undercurrent for the BJP – as evident from a raft of local polls held after demonetisation that BJP has swept – or not, this election in UP surely will break myths.

But, as the pundits say, the nature of the beast is such that it can only be either overestimated or underestimated. One thing is certain, if indeed the class is getting an upper hand on caste in this election, those walking away with the prize would be BJP and its campaigner-in-chief Narendra Modi.

Comments

0 comment