views

My daughter who is in Grade 1 was in her Hindi online class and while doing the akshar श्र they were asked to draw a श्रमिक (hard worker), without hesitation she drew me. Feeling very pleased with myself I went to my start-up office which is a co-working space. It struck me that there were precisely three women in the 25 seats in the bay. Not at all unusual for Delhi where the urban women employment rate is less than 10 per cent.

As a working professional and mum to a daughter, I am obsessed with getting more women to participate in the workforce. It is our moral and economic imperative to get women at work.

Jobs give women economic power. That is good news on multiple levels. It’s good for consumption, it improves health and education indicators for the family and ultimately results in higher human capital formation. Simply put, more skilled workers available for the economy set in motion a flywheel of sustainable growth.

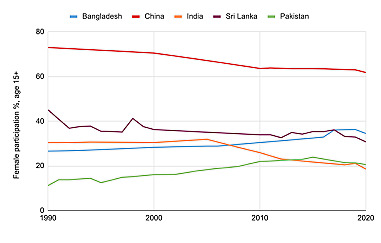

If you look at data from the 1990s till date, across most countries, women’s participation in the labour force has increased. It stands at 55-65 per cent for developed nations and 47 per cent on average.

India’s labour force participation rates have nearly halved in the same period! Our rate is significantly lower than Sri Lanka or Bangladesh which have witnessed high economic growth rates and improvement in human development indicators as more women have joined the workforce.

Source: World Bank, female labour force participation rates (%)

Often, you will hear three reasons to explain our falling participation. Let’s go over them in the context of India and you will see none of them can explain the decline.

1. Income effect: As countries grow richer, women who were at work to simply make ends meet, will sit it out. However as incomes continue to rise, a couple of structural shifts occur. More women get educated and fertility rates decline and women return to the workforce, in what economists call a U-shaped curve. In India, education levels have risen, fertility rates have fallen but women continue to sit it out.

2. Social norms: Women shoulder a very high percentage of domestic duties and unpaid care work. This is true but very comparable across several developing countries including our neighbours Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal. However, our participation for women is almost 14 percentage points lower.

3. Supply of jobs: Outside the unpaid or poorly paid farm sector roles, women are likely to over-index in certain set-ups. While India has not had garment growth story of Bangladesh, we have had solid growth in retail, hospitality, health, media and education sectors. Yet, even urban labour force participation rates have been declining.

So why is it that fewer women seek work despite rising education levels, more opportunities to work and an improving environment for work.

Enough said about our predicament but how do we climb out of this hole? I’m no organisation or policy expert but when we buck every trend, it needs a first principles approach to see if some distortions can result in a positive outcome.

ALSO READ | Women@Work: 20 Million Indian Women Quit Work in 5 Years – It is the Greatest Resignation Ever

How Do We Motivate More Women to Look for Work?

Re-imagine MNREGA: Since the early 1990s, rural female participation has fallen over 10 percentage points. With agricultural sector not providing adequate opportunities to women, re-imagining MNREGA could be a silver bullet for rural women. Already over 50 per cent of MNREGA participants are women, however the kind of jobs available remain restricted to agriculture, irrigation, sanitation which still tend to be fairly arduous for women. There is an opportunity here to reimagine MNREGA to offer jobs in healthcare, community and education. Frequently MNREGA demand outstrips supply; the government has an opportunity to correct this by simply looking at a few states as a pilot to assess the impact of the income multiplier.

Use tax code to incentivise work and continuity of work: In 1970, Sweden introduced a major change in personal income tax for women and while much is made of their great childcare and maternity policies, this is today acknowledged as a big contributor to getting women in the workforce. Till 2011 we did have lower tax rates for women, although the difference was little. To test if this works, we need a substantially lower tax rate for women across income levels. Also, it’s worth exploring some benefits, for e.g. lump sum deductions for continuing employment. Women could get deductions for completing 3/5/7 years of continuous employment. As a woman I can tell you, getting back to work after a break is very hard. If we are able to incentivise keeping women in their jobs, this could be powerful.

Codify flexibility: Childcare and managing the health of elders at home is a very real responsibility. Studies and surveys have shown that many more would work if they have solutions for managing kids and the elderly. Policy addressed this by putting the onus of creating creches on large employers (above 50 employees) and leaving compliance to states. We know that creches have not come up. They are not the answer. Virtual work for the most part of the last two years has shown us that flexibility in the form of remote work or hybrid work (limited virtual hours or days of the week) is a working model. Codifying flexibility (how many hours remote, pay for remote vs hybrid) is likely to be more productive than asking employers to comply with creche/day care norms. As the government looks at WFH norms, flexibility for women can liberate several skilled women who were looking for this opening.

ALSO READ | Missing Females: COVID-19 Underreporting among Women Exposes a Persistent and Global Problem

What Can We Do to Motivate Employers to Hire Women?

In India, the 26-week maternity leave is funded entirely by private sector companies. While this is great news for women’s welfare and their job security, it does distort incentives adversely for them. Employment rate for urban women has halved since the introduction of the maternity leave policy in 2017. In plain speak, employers are deterred from hiring women and the wage gap increases for women who are currently employed. Maternity leave at full pay is the right welfare tool but it will serve long-term good only if it is at least part funded by the government (or made tax deductible) as is the case in most countries.

Employers should be incentivised to make fresh women hires. Ensuring gender diversity on corporate boards via quotas is not the solution. Employers need to be monetarily incentivised through taxation or procurement incentives or subsidy to hire more women across levels. China is already considering providing preferential tax rates to companies who have higher women percentages employed. Recently, I read about Ola Electric’s all-women factory in Tamil Nadu. Such initiatives that provide higher than fair share of employment to women should receive procurement incentives or land/capital subsidies, incentivising employers to go the extra mile.

Of the 17 sustainable development goals, gender equality is at #5. Almost all MNCs operating in India are working towards these SDGs, but this is limited to their own offices or tying up with NGOs in specific areas. What if these MNCs introduced a minimum level of female employment by their suppliers and distributors as a pre-requisite for doing business with them? The positive domino effect would be huge.

Women’s participation in the workforce is perhaps the most important economic growth lever that is available to India and so far, all our initiatives have worsened the outcomes. Our policy efforts and private sector initiatives have pushed us in the opposite direction. Let’s accept that and move on from there.

We should try pilots across the board to see what sticks. Now is the time for radical experimentation. This is a problem worth solving, it’s our only shot at sustaining economic growth above 8 per cent. Doing the same things over and over again while expecting different outcomes isn’t sincere but insane.

ALSO READ | Women@Work: Can the F-word Be a Game Changer for Women’s Employment in India?

Simran Khara is a start-up founder. She is an alumnus of ISB, Hyderabad, London School of Economics (UK) and Shri Ram College of Commerce, Delhi University. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment