views

Women’s safety remains a concern in Haryana. However, the solution need not lie in state control. In the state of Haryana, an employer has to first obtain permission from the Labour Commissioner before he/she can hire women employees to work night shifts. This permission is given on a case-to-case basis and applicable to all sectors – a factory or a company writing algorithms.

Having a conditional relationship between women employees choosing to work night shifts and state permission is a multi-tiered problem. First, it underlines the failure of the state to ensure the safety of women; second, a faulty assumption that state approvals can ensure better safety of women; third, it induces discrimination against women at workplaces; fourth, it fails to distinguish between working conditions of sectors (like a software company vis-à-vis a warehouse) or background/literacy level of employees (blue collared worker vis-à-vis white collared worker); and finally, it is a nightmare for ease of doing business.

States like Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, and West Bengal where BFSI and the technology sector enjoy a reasonable presence have evolved their labour laws. Starting from the earlier position of prohibition, these states have adopted a self-regulatory regime where companies can engage women employees in night shifts, subject to strict checks and balances. However, Haryana with its license-permission-based regime, stands on a unique footing.

This post sheds light on the historical background of restrictions on women working night shifts, existing challenges with Haryana’s current policy and why Haryana needs a cue from other states.

Legacy of prohibition and evolution

Post World War I, women and children faced massive exploitation and many of them were forced to work in factories at night. Under the aegis of the ILO (Convention executed in 1919), several countries agreed to bring laws to bring an end to this practice. India as a founding member of ILO adopted this agreement which later got reflected under the Factories Act, 1948.[i]

Restriction under the 1919 ILO convention was meant for industrial establishments like mines, shipbuilding, and construction.[ii] India extended this to various commercial sectors like banks, hotels, IT companies, service sector, and shopping malls, under the different state Shops and Commercial Establishments legislations (SCE Act/laws).[iii]

However, with time and societal changes, laws change (the ILO convention has been abrogated). In 1990, ILO adopted a protocol known as the Protocol of 1990. Under those provisions, the competent authority in a country under its national laws and regulations is authorised to rectify the duration of the night shifts or to introduce exemptions from the ban on night work for women for certain branches of activity or occupations.

In 1999, the Madras High Court quashed the restriction under the Factories Act when it was challenged for violation of Articles 14, 15 and 16 of the constitution. In 2001, the Andhra Pradesh High Court delivered a similar verdict. After the high court decisions, the Factories Act was not amended to remove the prohibition. But different state governments issued notifications exempting factories from the prohibition, subject to certain conditions. In effect, women can now be employed in factories in night shifts i.e., from 07:00 PM to 06:00 AM.

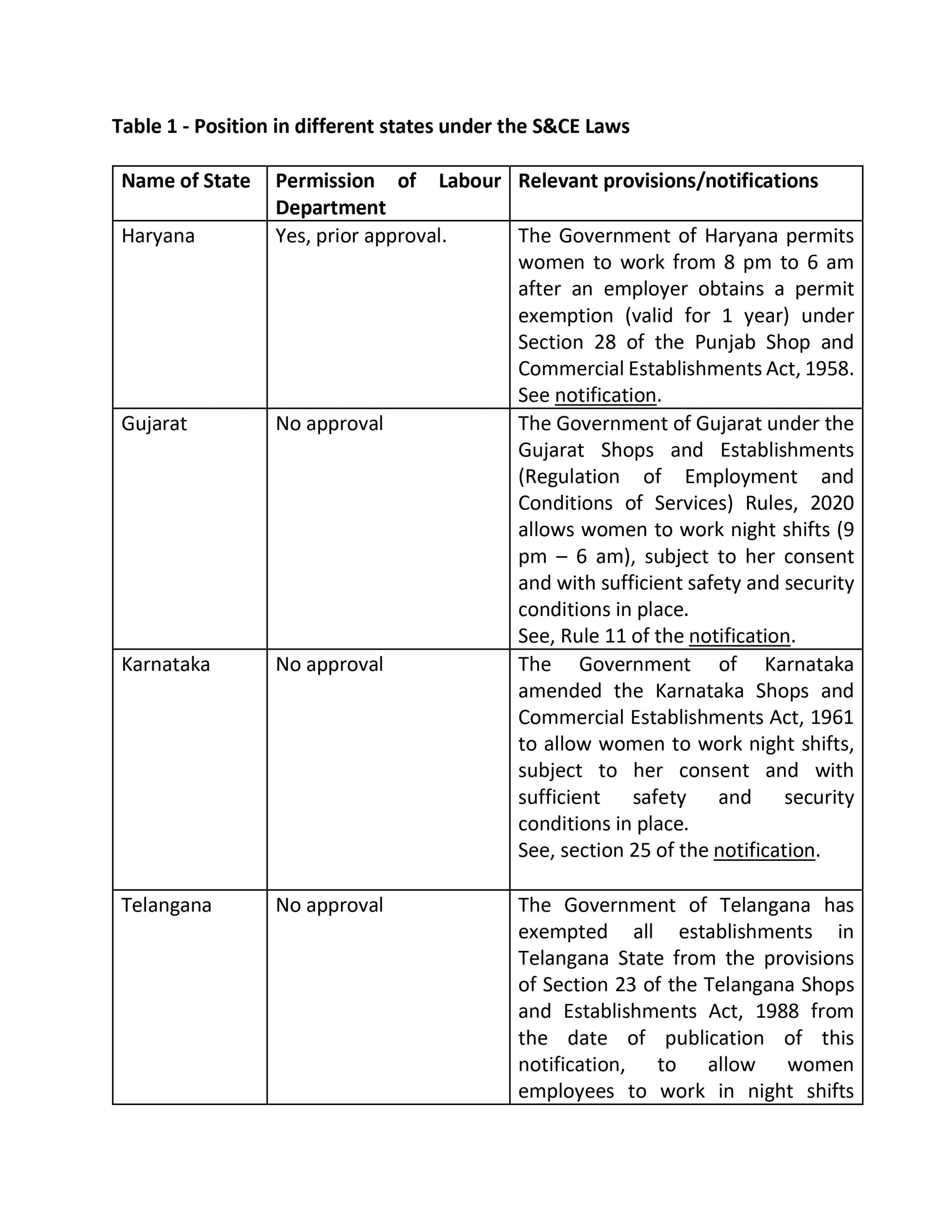

Similarly, under the respective SCE laws, several states removed the restriction (by allowing exemption, but not deleting/amend the prohibition from the statute book) on women working night shifts. For instance, states like Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, and West Bengal, where the service sector/IT/ITeS has a prominent presence, do not require permission from the labour department to hire women to work night shifts.

Broadly, these states require only two conditions to be met. First, the consent of the women employee, and second, the hiring company must have certain safety and security conditions, like night security guards, safe transportation, etc (See, Table 1).

Unique position in Haryana

As an outcome of the Madras High Court verdict, the Punjab SCE Act (applicable to Haryana) exempted offices from the prohibition to engage women employees in night shifts.[iv] However, this exemption is based on a license-permission system. Worse still, this permission was subject to the same set of obligations designed for women employees in factories working during night shifts.

To illustrate, factories are required to set up separate night canteens for women staff if their headcount is more than 50, install CCTV cameras inside transport vehicles, and ensure presence of a certain number of women employees and female security guards at night. These conditions were extended ‘as is’ to all sectors.

Clearly, this was a lack of application of mind because working conditions in the service sector cannot be equated with factories in terms of bargaining power of employees, nature of work done, literacy and background of employees, awareness of rights, recourse to professional help, compensation offered, etc.

For instance, a Global Capability Centre (GCCs are captive units of overseas companies, put crudely BPOs) doing high-end data processing work, will be allowed to hire women in night shifts only if it can hire a certain number of female staff & female security guards at night. This condition is both impractical and illogical. Eventually, difficulty in meeting these onerous requirements will result in companies preferring male employees and turning down women candidates to avoid non-compliance. This could result in de-facto discrimination against women. After several feedback and stakeholders’ representations, some of the conditions have been relaxed, however, there is a long way to go.

Bad laws do no good

The revised notification still requires a company to go back to the labour department and obtain fresh approval if there is any change in transport or security arrangements, like a change in vendor, etc. This is an irrational requirement because such changes are routine and the labour department has no expertise/capacity to verify whether the new vendor is good or bad. Unless the safety measures are not compromised, the labour department should not fiddle with day-to-day business decisions.

However, the biggest challenge is the duration of permission. At present, permission is granted for 1 year, making this a year-on-year compliance. Often obtaining permission is a time-consuming process. For example, companies have faced delays from 4 to 6 months with no reasons provided by the labour department, leaving companies in a state of uncertainty. Legally speaking, if such a company hires women in night shifts while the application is in process, it will amount to a violation. But if you wait, then approximately half of the year is gone. Perhaps companies in the real world take the risk and do not wait for so long. But it definitely raises eyebrows during internal risk assessments and audits.

Another pain point is the entire procedure is manual which makes it more cumbersome and inefficient. Neither the application can be filed online, nor its status can be tracked. Lastly, it is not clear whether these paper applications are digitised at some point of time. Since the application procedure requires the submission of women employee details who have given their consent to work night shifts, it is not clear whether such personal data, if maintained in non-digital form, would get protection under the recently legislated digital personal data protection laws.

Self-regulation, not state regulation

First, we need to question the assumption that state permission can ensure better safety of women. Ensuring law and order is the constitutional duty of the state and cannot be outsourced to a license-permit regime.

Second, we need a strong consent-driven regime where women employees can have quick recourse to remedy in the event they are forced/coerced to work night shifts or removed from work or subject to any other deterrence.

Third, strict and transparent disclosure of company practices should be done, like on the website of the company. Most employees may not know/care about the labour department’s permission. However, a female employee is entitled to know and would care about safety requirements and arrangements before she gives her consent.

Fourth, companies must self-certify through an undertaking towards compliance with women employees’ safety requirements. In the event of a breach, swift and strong sanctions must follow.

Fifth, the private sector must sensitise the labour department about the industry practices (especially differences between the service/tech sector and industrial establishments). This may bridge the trust deficit. State must acknowledge that it is in the interest of businesses to provide the best possible safety and security facilities to its women employees to avoid any reputational damage.

In sum, Haryana must take a cue from other Indian states that have adopted a pragmatic approach balancing both women’s safety and ease of business under the SCE laws. Especially, when states and nations are walking the extra mile to attract businesses, rudimentary labour laws are not going to help Haryana.

The writer is a public policy consultant. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

[i] Section 66(1)(b) of the Factories Act, 1948 says that no woman shall be required or allowed to work in any factory except between the hours of 6 am and 7 pm.

[ii] Article 1 of C004 – Night Work (Women) Convention, 1919 (No. 4).

[iii] While Factories Act govern factories, SCE laws regulate establishments, like, shopping malls, banks, hotels, IT companies, warehouses, etc.

[iv] Punjab Shops and Commercial Establishments Act, 1958 is applicable in the states of both Punjab and Haryana.

Comments

0 comment