views

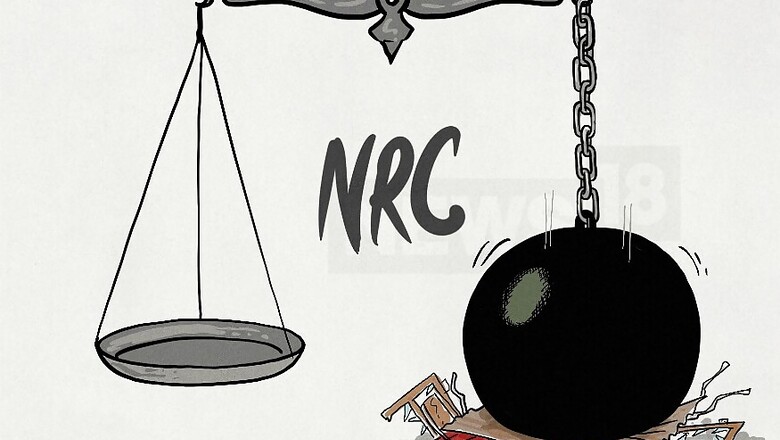

The National Register of Citizens (NRC), based on the three pillars of – detect, delete, deport – as we know now, has proved to be more complex, harrowing and impactful than one imagined. The fact that there were very few voices that challenged the very foundation of the whole exercise is testimony to how little information we had, how little invested we all were to the lives of those who were suspected of not being Indian citizens.

It is incredible that human rights advocates, progressive political activists and feminists, who make it their cause to fight for the oppressed, intellectuals, whose vocation it is to think of the public good, and the civil society did not feel obligated to take a concerted political stand on the whole issue to be deliberated and discussed before putting into practice. At best, a lot of people thought, rather wishfully, that the whole exercise would never come to any conclusive end and that it was bound to fail. The fact that this was markedly different from other kinds of identifications was hard to swallow.

It is indeed quite possible that we would not have seen the end result of the whole exercise had it not been for the congruence of different forces, such as the dedication given by the incumbent Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, that hastened the process, the bias political-bureaucratic decisions, such as inserting the category of ‘original inhabitants’.

But the neatness produced by those three words put together – detect, delete, deport – should worry us. In their combination, there is the sense of a clinical distance and indifference that they produce, as though we are no longer talking about human lives but bodies, things without any relations, ties, a perfect example of how to dehumanise a population.

We should be concerned that dehumanisation is the route through which worst atrocities, including mass-scale violence, take place. It is this dehumanisation that makes it normal, even rightful, for common people to participate in acts of the most violent kind. Be it colonialism, genocide, crimes against humanity. When the other, the enemy, is no longer seen as a human, it is easier for the members of the perpetrator community to act, and act to produce the most horrific violence.

At least we have the names and categories to describe this large-scale violence. Genocide in Rwanda; holocaust in Europe; communal violence in India; civil wars in many parts of the world; partition violence in South Asia.

But what do we call this – the making of stateless individuals by a democratic polity in order to fulfil the wishes of a popular movement? Perhaps, there is no historical precedent of this kind in which such a big number of people are made stateless through a bureaucratic process. Does this make what has happened more frightening for what may become of our future?

But now that the exercise is over, at least in Assam, going back to unbundle the whole exercise will no longer be permitted. What we can do, and what remains to be done, though, is the question of the present and the future: how does one engage with the lives of those who have been reduced to statelessness? How to humanise and challenge a political practice of dehumanisation?

The first task is to find the category to describe those who have not been included in the final NRC.

They are not migrants. Migrants would mean that they have a place of origin, which recognises and certifies them as its citizens. They are not refugees either, for refugees are politically recognised and have certain rights.

The only way in which these individuals can be described is in the negative — stateless, undocumented, non-citizen, illegal. They have ceased to belong to any recognized political community. The availability of options to prove otherwise is no consolation. Put simply, as long as the world is organised around the category of state-system, a person has to belong to one in order to have her/his rights, in the words of Hannah Arendt, ‘the right to have rights’. This is the foundation of the system that we inhabit today. In other words, these individuals who have been excluded from the NRC cease to have any right.

It is a reality that – unless the individuals are able to prove otherwise – those whose names do not figure in the NRC list are not Indian citizens, anymore. They exist in a suspended legal status. If they are unable to provide convincing documents, thus failing to put their names back into the list, then they will lose being Indian citizens and become stateless, non-citizens who would be disenfranchised, dispossessed, and disposable bodies.

That the exclusion figure for the Bengal-origin Muslim inhabitants of Assam is lower than the popular belief has made a section of the people in Assam already unhappy with the outcome. It is true that people, cutting across religious and ethnic lines, supported the NRC in Assam hoping that it would solve the vexed issue of immigration once and for all. But now that the results are out, dissatisfaction has already set in. This is a reminder of how there are many other faultlines based on language, ethnicity that can be used for dangerous political mobilisation. That a social, political issue cannot be resolved by bureaucratic means has been made abundantly clear from this whole exercise. Whatever assessment of the whole exercise we do, it should be informed by the realisation that harassment and exploitation of the poor, the disenfranchised, the dispossessed will continue, irrespective of what course follows in the aftermath of the NRC, unless, of course, we act in concert against such practices.

(The author is assistant professor at the Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Guwahati. Views Expressed are personal.)

Comments

0 comment