views

We have seen extreme fantastical vilification by people like James Todd, while there is extreme eulogizing by others. There are many promoting the Tīmūrids (in the name of Moghūls) for good. But if I look at the records of Tīmūrids themselves, it seems that had any one of them been alive, they would have possibly rejected all these narratives of glorification. And the texts like the Baburnama etc. stand aloud as the testimony of this matter. In the world of Turco-Mongols, secularism as it is glorified today, was never a virtue of glory back then.

It all begins with the name itself. They have always been addressed as Moghūls, but did they ever address themselves as so? While penning the Baburnama, Babur ensured a clear distinction between him being a Tīmūrid Prince establishing a Tīmūrid Gūrkāniyān Sult̤ānate and not the Moghūl, which has been a popular claim of late. One may argue that Babur may have not used the term ‘Moghūl’ at all and hence the different term. But that too is not the reality. Babur has used the term ‘Moghūl/ Mūghal/Mūgal’ more than 400 times in the Baburnama drawing a clear distinction. In fact, he has the worst opinion of the ‘Moghūl clan’.

But the question that may arise is why should we bring in the name of the clan while we are just chronicling their history? The answer lies in the fact that even this name distortion occurred only because there was something to hide. Humbly speaking, the wrong name was used to create a narrative. Or else why suddenly in the nineteenth century, Indologists would begin calling Tīmūrid Gūrkāniyān Mūghals almost after three centuries of their establishment in what they called Hindustan. Abul-Fazl in the Ain-e-Akbari does mention them being the empire of ‘Hindustan’.

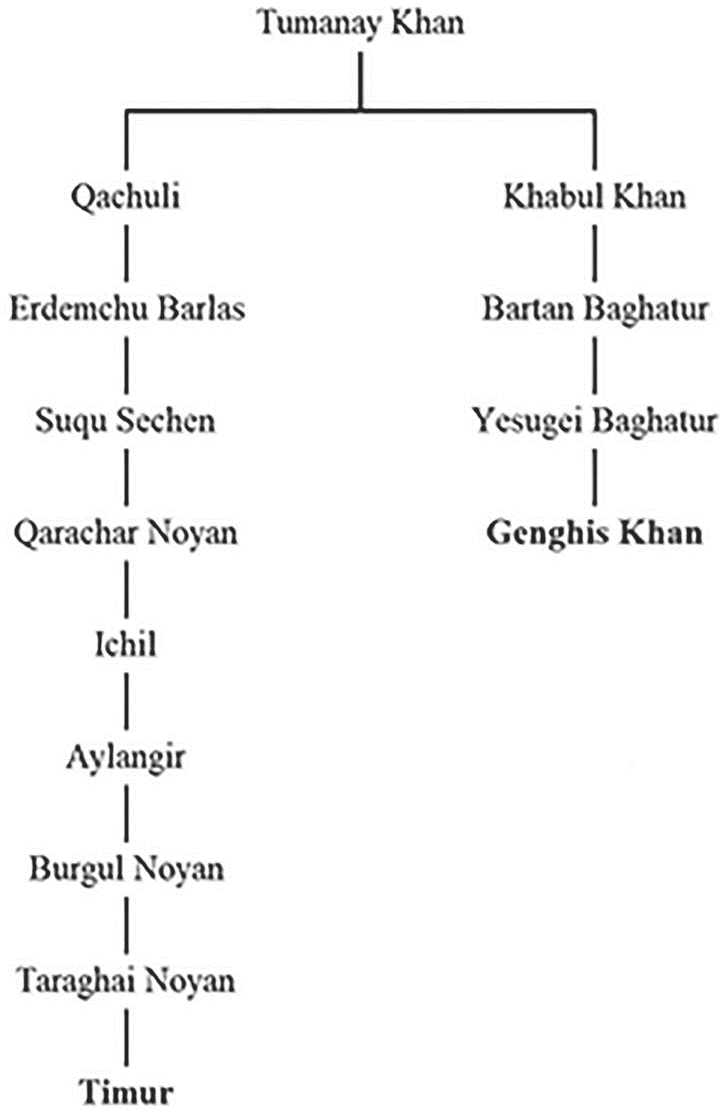

So, coming back to the name, Timur never liked to see himself as Moghūl even though both him and Genghis Khān had a common ancestor Tumanay Khān (Figure 1). Timur was in the tenth generation while Ghengis was in the fifth generation.

Babur’s ancestors were sharply distinguished from the classical Mongols (Moghūls) insofar as they were oriented towards Persian rather than Turco-Mongol culture. According to John Joseph Saunders, ‘Timur was “the product of an Islamized and Iranized society”, and not steppe nomadic (Mongols).’

If one looks at Timur’s character, he was an opportunist. Taking advantage of his Turco-Mongolian heritage, he frequently used either the religion of Islam, Sharia law, fiqh, or traditions of the Mongol Empire to achieve his military goals and domestic political aims. This exactly was the trait of those whom we call Moghūls from the period of ad 1526 onwards. They had all the barbaric traits of the steppe nomads, but the same would be reflected when Persian strategies failed to core.

Though barbaric, the Mongol Empire was known to be highly secular and tolerant towards all existing faiths. In fact, after having given protection to the Muslims, Genghis Khān earned the title of ‘defender of religions’. What is very interesting is that the Mongol passion for religious tolerance charmed the European writers of the eighteenth century very broadly. Edward Gibbon, an English historian writes in a celebrated passage, ‘The Catholic inquisitors of Europe, who defended nonsense by cruelty, might have been confounded by the example of a barbarian, who anticipated the lessons of philosophy and established by his laws a system of pure theism and perfect toleration.’ He goes on to add, in a footnote that ‘singular conformity may be found between the religious laws of Zingis Khān and Mr. Locke’. Well, for people who don’t know about John Locke (29 August 1632–28 October 1704)—he was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential ‘enlightenment thinkers’ and commonly known as the ‘Father of Liberalism’. He had influenced people like Voltaire. Perhaps the European idea of imperialism had a façade of liberalism and secularism which appeared as a cool buttress.

In contrast, Timur had a record of persecution in the name of religion. As explained earlier, Timur had a high Persian influence. Before he could lay the siege of Persia, the condition of Christians was already horrendous with the rise of Islam as the ‘state religion’ for a long.

The history of the church in Asia in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries was very much tied up with the rise of the Mongol/Moghūl power under Hulegu, Kublai and Timur. The first two were brothers, sons of the Nestorian princes Sorkaktani and were known to be protectors of Christians while Timur became known for their destruction.

And in the year fifteen hundred and seventy-six of the Greeks (a.d. 1265), in the days which introduced the Fast [of nineveh], Hulegu, King of Kings, departed from this world. The wisdom of this man, and his greatness of soul, and his wonderful actions are incomparable. And in the days of summer Tokuz Khatun, the believing queen, departed, and great sorrow came to all the Christians throughout the world because of the departure of these two great lights, who made the Christian religion triumphant.

The Mongol ruler of Persia (IlKhān), Ghazan (ad 1295–1304) converted to Islam and what followed was highly disastrous. The systematic persecution of Christians, Jews and Buddhists had become vogue, and their places were destroyed at a huge pace. The initial days of Mongol rule had seen Christians being favoured extensively, but since the Islamic Conversion and after a lapse of seven decades, Islam had yet again risen as the state religion in Persia, changing things from how they were earlier.

Bar Hebraeus in his chronography describes the conditions of the Christians as extremely horrible. He writes: No Christian dared to appear in the streets (or market), but the women went out and came in and bought and sold, because they could not be distinguished from the Arab women, and could not be identified as Christians, though those who were recognized as Christians were disgraced, and slapped, and beaten and mocked.

The persecution of Christians continued unabated under the subsequent IlKhāns. With the dawn of the 1340s, the Mongol power began to cease as Timur took control. Timur was clear and sound, knowing exactly what he wanted. He wanted to revive an Islamic Caliphate by hook or by crook with a definitive plan to make Samarkand the capital of Asia. One can say that he was a great conqueror concerning the parameters set in the West and the Middle East, but, in our eyes, was the image made up of his extreme brutalities. Between ad 1380 and ad 1393, Timur captured Central Asia, Persia, Egypt and the northern parts of India. By ad 1383, Baghdad, with the unabridged Mesopotamia, was completely under his control the route to which was indeed horrific to the indigenous people. As per the witness accounts, Timur had made twenty towers of skulls, each having a minimum of fifteen hundred, in the ruins of Isfahan and Baghdad. Few historians describe a ‘systematic use of terror against towns’, as ‘Tamerlane’s strategic element’. This was also a ploy through precedents by which he would avoid bloodshed. The widespread fear precluded any resistance as people chose to submit instead. But at the same time, his massacres were highly selective, and he spared the people who in his eyes were experts of art and knowledge to some extent. Undoubtedly, this is the same model that Babur and his successors followed. This was not the Mongol or Moghūl case in general.

In India, he captured and ordered the execution of a hundred thousand prisoners to free his soldiers thereby concretizing his aspiration of Delhi. Of course, within these misfortunes, both Muslims and non-Muslims suffered despite the intention being to target non-Muslims largely. Unlike the general Mongol traditions of governance, Timur ensured systematic persecution on account of religion.

The control of Delhi was one of the very important victories of Timur. And why not? Delhi was one of the richest cities in the world back then. Retaliations began after Delhi fell into his hands. Timur led the Turco-Mongol Army and inflicted massive bloodshed and massacres against all the retaliations within the city walls. After three days of tussling between resisting forces and the Turco-Mongol Army, it is said that the city smelt of the decomposing bodies of its sons with their heads being placed over one another and the bodies left as food for the birds by Timur’s soldiers. This destruction of Delhi had opened the doors for long-lasting chaos that would consume India for long. The great city of Delhi founded by Anangpal Tomar would not be able to recover from the great loss it suffered for at least centuries.

As stated earlier, Timur was an excellent politician. The precedents that follow would prove this case.

Timur’s Turco-Mongolian heritage offered him both prospects and contests. He had all desires to rule the Muslim world, being the head of the Mongol Empire. But the existing Mongol tradition posed outright trouble for his ambition. He was not the direct descendant of Genghis Khān (refer to Figure 1) and hence he couldn’t claim the title of ‘the Khān’ or rule the ‘Mongol Empire’.

Henceforth, the cunning Timur set up a puppet in Chaghatay Khān, Suyurghatmish, as the titular ruler of Balkh by pretending to be a ‘protector of the member of a Chinggisid line (Genghis Khān’s eldest son, Jochi).’ At the same time, Timur took up the title of ‘Amir’. It was as good as not only being the general but also acting in the name of the Chagatai ruler of Transoxiana.

To underpin this position, Timur further claimed the title ‘Guregen’ (royal son-in-law) when he married Saray Mulk Khānum, a princess of Chinggisid descent.

While Timur aspired to rule both the Muslim and Mongol worlds, he could neither take the title of ‘Khān’ nor he could become the ‘Caliph’, as the latter’s office was limited to the tribe of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh). Hence to solve this crisis, Timur did something very different (later his successor Abu’l-Fath Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar would do something similar in the sixteenth century). Timur got a myth formulized and portrayed himself as a ‘supernatural personal power’ ordained by God (say, Allah). Interestingly and radically enough, this myth was propagated that he was a spiritual descendant of Ali, thus linking his lineage to both Genghis Khān and the Quraysh.

So, this makes the narrative clear that Timur aspired to become powerful by hook or crook. He wanted to be known as the head of all humanity without compromising on principles laid by Prophet Muhammad (pbuh).

This sets the precedent very correctly for Babur who established a ‘Tīmūrid Empire’ in India to push for not only Islamism but also to retain control over the Mongols. He simply meant business and being a follower of Timur, he would not shy away from inflating and using religion whenever required.

Perhaps intolerance was a part of their conduct and it would be dishonest to expect the progenies of Timur to begin a new chapter of tolerance. If one understands ‘Timur’ it will not be tough to get into the psyche of the politics of Babur and his successors. Not to forget, the history of Timur had a strong impact on Babur.

Before this project of books on the Tīmūrid Gūrkāniyān, I deep-dived into the lives of Babur, Humayun, Akbar and Aurangzeb. Their religious and economic policies were very clear to me but as research progressed, a lot opened even about Jahangir and Shah Jahan. It was quite astonishing for me to discover that Jahangir began his tourney as the king of the Tīmūrid Empire, who was intolerant towards non-Muslims. Earlier Jahangir’s image was known to me as the ‘Salim’ of Mughal-e-Azam, but the historical records didn’t agree with my impression of him. The maiden farmans of him indicated very strongly that he wanted to make his empire into a hardcore Islamist one. Although people talk of his drug and alcohol addictions, with fervour to show how distant he was from Islam in his own words, he had asked the Ulemas to prepare a set of ‘idiosyncratic appeals to Allah’ which he could easily remember and repeat without any disturbance on his rosary. His sadistic nature is also well-recorded in his writings. When he went to war against Mewar, he declared it to be a qital fi sabilillah. Many mandirs were destroyed in this campaign. Similar emotions reigned high in his Kangra Campaign of ad 1621. His aggression against the Sikh Guru Arjun Dev too is very well recorded. Guru Arjun Dev was killed after being brutally tortured by Jahangir. Jahangir’s ill-treatment of Guru Arjun Dev’s successor, Guru Hargobind, too has been well recorded.

Jahangir went overboard in penalizing anyone who disagreed with him. During his reign, many prominent Muslims had disagreements with him, after which they couldn’t escape his wrath however important they were to the society. The noteworthy Sufi Sheikh Ahmad Sirhindi once pronounced that ‘he once came closer to Allah than the Caliphs in his dreams’. This made Jahangir furious as he saw this as an insult to the Caliphs. Yet another Sufi named Sheikh Nizam Thanesari was expatriated to Mecca on the charge of accompanying Khusrau Mirza.

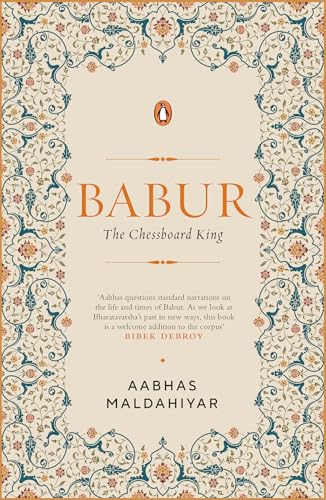

The author is an architect and historian. This extract has been taken from his introduction to his book, ‘Babur: The Chessboard King’, with the permission of the publisher. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment