views

Does India have “no moral conflict” in buying Russian oil? Did it have “any qualms” about continuing to buy from Russia? The most striking feature of CNN anchor Becky Anderson’s recent interview of India’s Minister of Petroleum and Natural Gas Hardeep Singh Puri was the insistent moral outrage. The 8.53- minute video clip of the CNN Connect interview which Andersen later tweeted – explicitly prefacing it with the question of “moral conflict” – is suffused with this trope. Despite Puri’s firm fact-based rebuttal that India’s imports of Russian oil only amounted “in a quarter” to “what Europe buys in an afternoon,” the question, like a yo-yo, kept coming back continuously.

Framing matters. And the interview was a prime example of the problem with much of mainstream Western media and its simplistic depictions of India. Especially since the rise of the Narendra Modi regime, this global narrative by leading editorial gatekeepers, with honorable exceptions, has generally been marked with a special kind of derision, opprobrium and exasperation with India.

Juxtaposing the facts on Russian oil supplies with the global reality and the simplistic CNN narrative on India is instructive.

• Russia earned about EUR 208 billion in revenue from fossil fuel exports since its invasion of Ukraine began. More than half of these estimated Russian energy export earnings – EUR 108 billion – came from European Union countries, estimates CREA (The Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air).

• The EU officially banned Russian oil imports on May 30, 2022. But, Russia has been “pumping more oil to Europe than it was before the war,” as The Economist found in a recent review. Russian oil supplies to EU rose by 14% between January-April 22.

• Of course, EU energy imports from Russia overall have been falling as countries look for alternatives. Yet, as the International Energy Agency (IEA) recently estimated, the EU remains the “biggest market for Russian crude.”

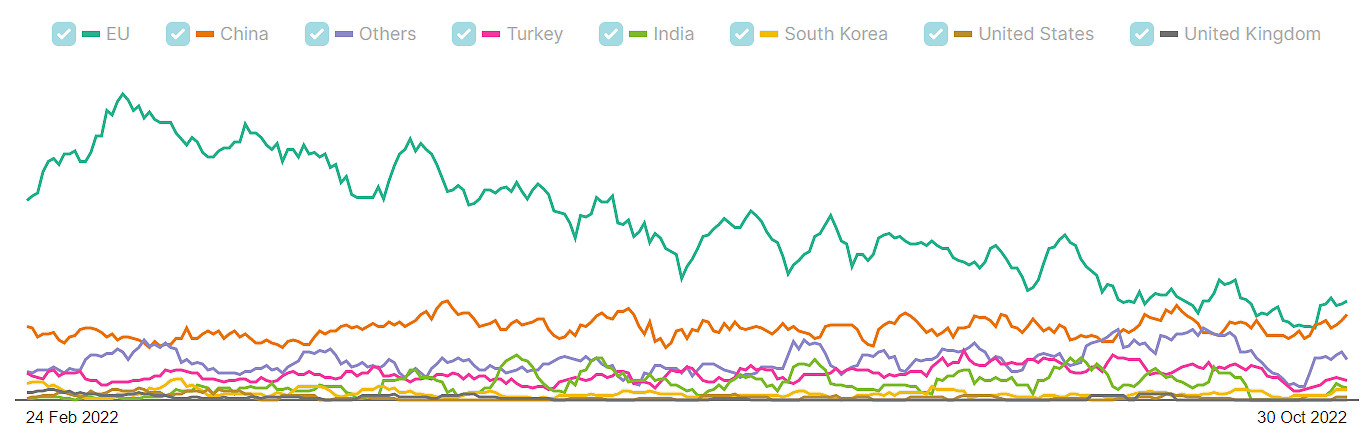

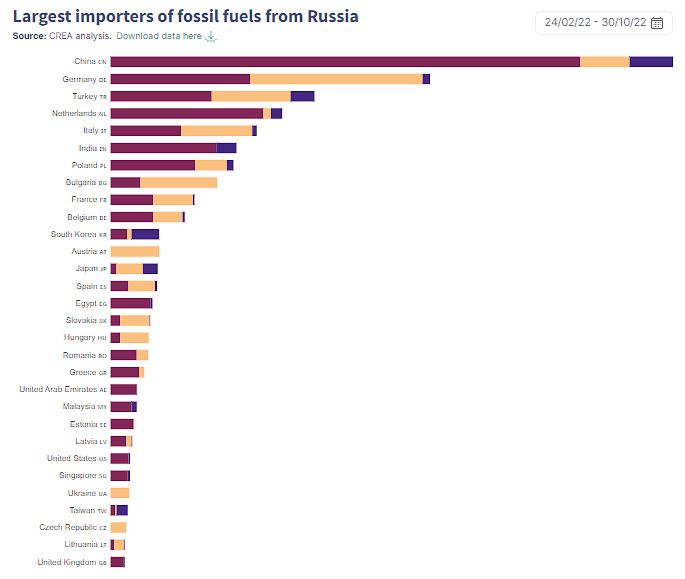

The data on Russian energy imports, country-by-country, is revealing (see Figure 1).

Among countries, China, Germany, Turkey, Netherlands and Italy have all been importing far more Russian energy than India.

Source: Charts from Russia Fossil Tracker, CREA, https://www.russiafossiltracker.com/en

The EU, overall, takes the lion’s share, even if it has been reducing its share. Yet, have you ever heard a CNN or BBC anchor berating the German foreign minister or the EU foreign policy head about “moral conflict”? If this is not double standards and hypocrisy, what is?

Western Media and India

While it would be too simplistic to lump all journalists and networks in one simple box, the hectoring, finger-wagging tone of the Anderson interview is broadly representative of a general mindset and trope that seems to bind much of mainstream Western media coverage of India, especially in the UK and USA.

At a broader level, a recent peer-reviewed analysis of over 3,000 articles in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, TIME and Guardian gives much food for thought. Randomly sampling 500 of articles from this lot (100 from each publication), Amol Parth, now with Prasar Bharti, found that 10 words featured most prominently in the headlines: Fear, Hate, Violence, Riot, Hindu, Muslim, Kashmir, Cow, Mob, Protest. In other words, the framing language fits only one specific narrative on India.

This analysis reminded me of a telling private conversation with a senior liberal journalist a couple of years back who told me that when she sent in pieces to some prominent Western publications, who paid very well by Indian media standards, the op-ed editors only wanted one kind of India piece. They wouldn’t publish anything else. And this journalist didn’t want to write one-sided pieces. Such pieces, she felt, would damage her credibility as an honest and knowledgeable interlocutor on India.

A case in point is a recent The New York Times piece published soon after India overtook the UK to become the world’s fifth largest economy in September 2022. I noticed it in the paper’s international edition in Tel Aviv. The front-page article, sporting PM Narendra Modi’s visage essentially berated Western capitals for cosying up to New Delhi as global power equations shift. Describing India as an “ambitious”, “assertive” and “indispensable” power for countering the world’s biggest challenges, the writer seemed outraged that Western capitals had done “little pushback” on what it called Mr Modi’s “project to remake India’s democracy” and imprinting a “Hindu majoritarian ideology on India’s constitutionally secular democracy.”

Essentially, this was opinion-writing, masquerading as reportage on the front pages.

Of course, anyone can have a critical view – it is part of the job-description of journalism. But the question is: do western media entities provide a balanced view of India to their readers? Or, just a one lop-sided view, aligned with their own preferences and echo chambers — as opposed to balanced journalistic reportage? Does this kind of editorial gatekeeping, then, only serve to reinforce simplistic stereotypes and end up misleading readers?

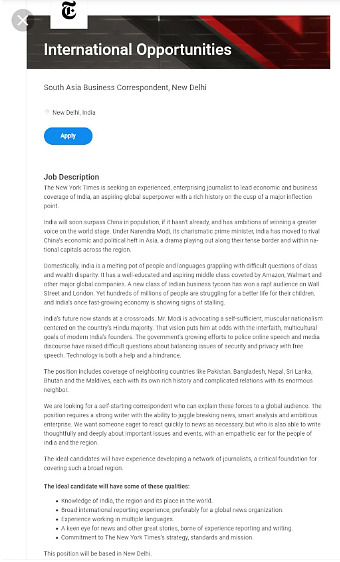

When The New York Times advertised in 2021 for a business correspondent in South Asia, its publicly advertised job posting itself was specific. “India’s future now stands at a crossroads,” the advert declared. “Mr. Modi is advocating a self-sufficient, muscular nationalism centered on the country’s Hindu majority. That vision puts him at odds with the interfaith, multicultural goals of modern India’s founders. The government’s growing efforts to police online speech and media discourse have raised difficult questions about balancing issues of security and privacy with free speech.”

It was strange language for a job posting. This was an editorial viewpoint for the opinion pages that had seeped even into an HR job description. It implied that only one kind of viewpoint may fit this job. The NYT, for instance, didn’t seem to have such descriptions for jobs advertised for Hong Kong or elsewhere.

Five Reasons for Western Meta Narratives on India

There are five broad reasons for the way these echo chamber narratives are framed. First, while there is sharp cleavage in India between those who support Modi and believe his ascent signifies a major course-correction for the nation Vs. many of the old liberal elite — the “anti-Modi liberal clergy” as it were — the vast majority in India is neither Left nor Right. Yet, as Swati and Ramesh Ramanathan, co-founders of the Janaagrah Center for Citizenship and Democracy have pointed out, the “corrosive debate” between the two sides means that irrespective of reason, serious debates often get “trivialised into a Modi litmus test.”

The example of the Freedom House Report on Democracy, which they posit, is revealing. In 2022, this Report gave a score of 66 to India on its “global freedom score” and as a “partly-free” country. Yet, the same index rated civil liberties in India at 33, the same score as for Hong Kong. In 2021, soon after China passed a new national security law that upended Hong Kong’s politics, India score of 33 on civil liberties came in lower than that of Hong Kong’s at 40. “Given all that‘s happened in Hong Kong, it’s ludicrous for even the most trenchant critic of the Modi regime to agree with these assessments,” Ramanathan and Ramanathan have argued.

Second, this happens because many of these rankings are based on surveys with intellectuals, academics, think tanks etc. Sociologist Salvatore Babones, who teaches at the University of Sydney, recently argued, in comments that went viral on social media that the problem is “not that the institutions who measure are biased. The problem is that India’s intellectual class is anti-India… Not as individuals, but as a class they are certainly anti-BJP.”

To be clear, he wasn’t conflating Modi and the nation. He was making the more sophisticated point about whether the people surveyed would give similar ratings for the same actions by a future Congress government, as opposed to those by a BJP government. In other words, he was pointing to the problem of politically colour coded echo chambers.

Third, with honourable exceptions, many Western journalists fundamentally rely for their information on India on precisely the same interlocutors. What this means is that only one view of India forms the global narrative. The real picture may be much more nuanced. For example, when the web portal The Wire published an investigation into TekFog, a supposed super app it claimed the BJP used to automate hate on social media, many in the western press bought it uncritically. When the data scientist Samarth Bansal published a detailed story raising doubts on its findings, not many gave it credence. The Washington Post published a detailed opinion piece treating The Wire’s TekFog investigation as gospel truth.

Yet, now that The Wire has been forced to retract yet another investigation that wrongly claimed that the BJP IT cell head Amit Malviya had what has been called God powers from Meta to take down posts by users, the TekFog story has also been withdrawn. In this case, The Wire’s backtracking happened because many leading tech voices in the Silicon Valley who have a strong and credible record of questioning Big Tech raised questions about its investigation. Yet, the TekFog piece published by the WaPo is yet to be withdrawn. A week after The Wire withdrew its reportage, WaPo’s editor, on November 3, 2022 did add a note on top of the piece acknowledging that “the investigative series about the Tek Fog app that this column draws upon has been removed from public view pending a review by the publication the Wire.” Yet, strangely, the article itself remains.

In contrast, The Editors Guild of India on October 28, formally withdrew previous statements it had issued based on the Tek Fog reportage. As it said in a signed statement, “since the Wire has removed these [Tek Fog] stories as part of their internal review following serious questions on the veracity of their reporting, the Guild withdraws the references made to these reports.”

Fourth, some of the lack of nuance on Western coverage of India comes from ignorance and what the Columbia University professor Edward Said called ‘Orientalism’. This was his seminal work on how the West constructed the idea of the ‘Orient’ as the childish, somehow less-intelligent ‘Other’, in opposition to its own self-image of superiority and rationality. Even India’s first prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, in his first ever TV interview, was lectured by tut-tutting BBC interviewers that “what is worrying many of us is your democratic system.” They added that there “doesn’t seem to be an opposition” in your country. Nehru’s acerbic response is worth repeating: “What do you mean by that? In our Parliament, we have 500 MPs. We have 350. The Opposition is 150. They are split up in many parts and we don’t have a two-party system but we can’t impose that…But there is an Opposition and a very good Opposition and it continues to oppose us both inside and outside Parliament.” This trope of the “death of Indian democracy” continued through the 1960s. A good illustration of this is the oft-quoted but famously wrong analysis of Indian politics in 1967 by a correspondent of The Times (of London), Neville Maxwell. He wrote a two-part series titled, ‘India’s Disintegrating Democracy’, which predicted that the coming election would ‘surely’ be its last. The point is that some of these mental maps and attitudes long predate the Modi government. But they have an extra edge now, because the social structure of the BJP is very different from that of past regimes.

Finally, in an age of digital connectivity and transparency, western media attitudes of condescension, fuelled by ignorance and based on older cultural power structures may be past their use-by-date. When the Western media networks, like in the Anderson interview, hold up different standards for India compared to say Germany or the EU, it impacts their credibility as honest chroniclers of our times in many Indian eyes.

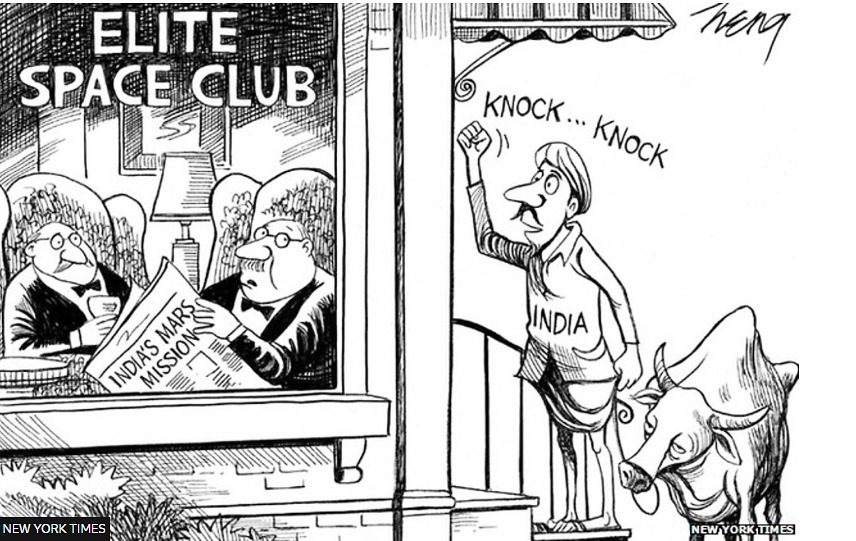

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/29/opinion/heng-indias-budget-mission-to-mars.html?_r=1

At a time when many Indians see their country as a rising power, the Anderson’s hectoring, the constant references in it to “Western sanctions” and the incredulity at an Indian minister’s confident pushback was reminiscent of the same school of thought that animated The New York Times’ unfortunate cartoon a few years back when India launched its Mars mission. It had depicted a rustic Indian man in a dhoti and turban with a cow knocking in vain at the closed doors of a Western saloon marked “Elite Space Club.” The newspaper eventually apologised for that racist cartoon but the broader editorial playbook where it came from is alive and well.

Nalin Mehta, an author and academic, is the Dean of School of Modern Media at UPES University in Dehradun, a Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Institute of South Asian Studies at the National University Singapore, and Group Consulting Editor, Network 18. He is the author of The New BJP: Modi and the Making of the World’s Largest Political Party, Westland.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment