views

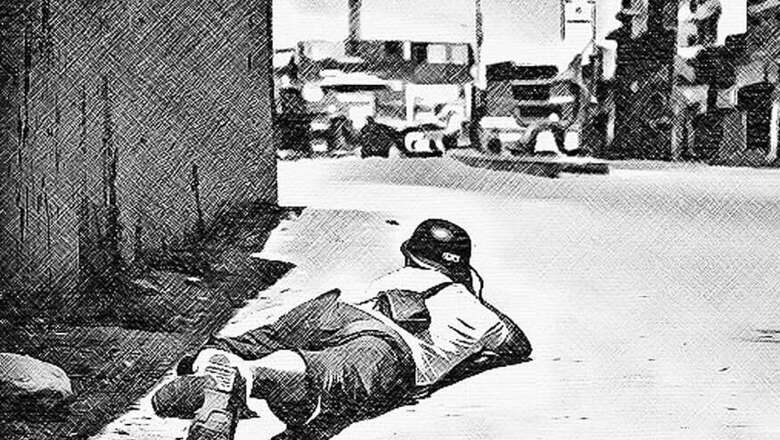

Abu Bakar had done it many times before. He was running towards something that everyone else was running away from. He was going to do his job: to document a street protest in North Kashmir’s Sopore. Scores of students had come on streets this summer in Bakar’s own backyard.

The 21-year-old freelance photojournalist packed his camera and crossed the narrow alleys of his hometown to reach to the spot. Students — armed with stones and shouldering their school bags — were engaged in a pitched battle with the security forces. Bakar started clicking photographs like every other day.

Minutes later, he heard someone shouting his name and abusing him.

“It was a senior police officer. He screamed that he would kill me in an encounter if I didn’t stop taking the photos. He didn’t want me to take the pictures of his men teargassing the youths in school uniform,” Bakar told News18.

Photo Credit: Mohammad Abu Bakar

SHOOTING THE MESSENGER

On September 4, Kamran Yusuf, a freelance photojournalist working in South Kashmir, was arrested by the National Investigation Agency (NIA) and flown to Delhi. Kamran is a regular contributor to Kashmir’s largest circulated English daily — Greater Kashmir. His work has been published in other local newspapers as well, including some television channels.

It has been a week since Kamran has been in NIA custody. “We have booked him under stone pelting charges. He will soon be produced before a court,” said Alok Mittal, spokesperson of NIA.

Kamran’s family and colleagues, however, have denied the charges. The 20-year-old photojournalist lives in Pulwama’s Tahab village and was raised by his mother after she got divorced when Kamran was two. Rubeena said her son was carrying out his professional duties and that he has no links with stone throwing.

Journalists across Kashmir have protested the detention and asked the NIA to explain the charges against him. On September 12, The Kashmir Editors Guild (KEG) asked authorities to “immediately” release the photojournalist.

Same day, The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), an international NGO for press freedom, said, “Indian authorities should immediately release freelance photojournalist Kamran Yousuf who has been held without charge.”

Many in Kashmir’s media fraternity, however, believe that Kamran was arrested because “he reported stories nobody else used to.”

Shah Irshad, who works as a photojournalist for a Delhi-based organization and is a close friend of Kamran said, “He [Kamran] used to report from the ground and told stories about human right violations and police excesses.”

Another journalist from South Kashmir, while wishing to remain anonymous, said Kamran was framed because he had “become an eye sore for some politicians in the area and they didn’t like the work he was doing”.

On March 4 this year, Kamran was beaten up. Greater Kashmir in its story about the incident quoted him saying, “As the clashes erupted in the town, I rushed to the spot to cover the incident. However, policemen present there pounced on me and beat me. They threatened to break my camera. Somehow I regained my composure and managed to escape from the spot.”

The story titled ‘Cops thrash GK lensman’ has since been deleted from the Greater Kashmir website after Kamran’s arrest by the NIA.

However, Greater Kashmir editor-in-chief Fayaz Ahmad Kaloo, in an interview with The Hoot, a media watchdog, said that Yousuf was not on the payroll. “I would have owned him if he had worked with us. He was not a staffer and did not carry our I-card. He would send photos to all news organisations in 2016 and his photos were used. I would not have unnecessarily made it an issue,” he said.

Kamran’s friend and mentor Irshad shrugs off Greater Kashmir’s position on the matter. “The organization owned him when he was beaten in May this year. Why did they remove the story from their website which said he was beaten up by cops?” he questioned.

But for journalists who have known Kamran closely, his arrest by the NIA is not only an issue of ‘gagging the press’, but also to make sure other journalists keep it in mind while covering the Kashmir conflict.

Photo Credit: Mohammad Abu Bakar

“He (Kamran) covered almost every encounter and militant funeral in South Kashmir. His pictures used to go viral and the authorities didn’t like that. His arrest is a message to all of us,” a journalist from South Kashmir said.

IN THE LINE OF FIRE

Caught in the line of fire when they are covering the violence, these photojournalists — young and experienced alike — feel duty-bound to report the stories. But one can’t ignore the harsh reality that has come to fore: how the authorities in Kashmir are treating the local photojournalists — the first-responders to the news.

The recent example of one such case is a 30-year-old freelance photojournalist Zuhaib Maqbool. Zuhaib is a victim of the pellet guns used by the police against the protestors in Kashmir. On September 4, 2016, he was hit in the face by the pellets fired by the cops while covering protests in the Rainawari locality of Srinagar.

“I saw a masked cop pointing his gun towards me and I immediately stood up. As he was about to press the trigger, I showed my camera shouting ‘I am from the press’. Within few seconds, I heard a loud bang with some hot metal objects hitting my body and eyes,” Zuhaib said.

After he was hit by pellets, Freelance photojournalist Zuhaib Maqbool lost partial eyesight in his left eye. (Getty Images)

Zuhaib and his colleagues, who were with him that day, say there was no provocation. “They knew we were from the media, and yet they fired at Zuhaib from close range. No action has been taken against the cop who fired at him,” said one of Zuhaib’s colleagues.

Zuhaib’s isn’t the only such case. The cops had beaten up many photojournalists during the 2016 unrest as well. The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) in September 2016, its statement condemned these attacks and expressed concerns over press freedom in Kashmir. “We demand that the government not only allows journalists to report freely but also to ensure their protection,” the statement read.

However, in most of these cases, police and the authorities have blamed the photojournalists for ‘being at a wrong place’ or even ‘instigating the trouble’.

But photojournalists in Kashmir haven’t only borne the brunt from one side. Those who cover protests and militant funerals are facing heat from protesters as well.

Syed Shehriyar, a young photojournalist who has been covering Kashmir for 6 years, has experienced hostility from both sides. There were times when the police harassed him as he was taking pictures and other times when he was threatened by protesters.

“We face the stick from both the parties. Police say we glorify the civilian protesters and protesters say we sell our photos to the security agencies. We have been living with all this,” Shehriyar said.

UNFAZED AND UNDETERRED

Javed Dar, an award-winning journalist from Kashmir who works with a foreign publication and has been covering Kashmir for 15 years, says photojournalists are not to be blamed for the crises.

“We are only doing our job. The problem occurs when the authorities and people at large presume photojournalists are instigators of the crises, and with that the friction starts and photojournalists become a target. Clashes between protesters and security forces happen even in our absence,” Dar said.

Dar pointed out that photojournalists have not only documented funerals of militants and police excesses, “the heart-rending picture of wailing Zohra, the daughter of police officer who was killed by the militants, was also clicked by us.”

A journalist who was on a recent reporting trip to Kashmir shared an interesting anecdote that sums up how journalists and photojournalists in Kashmir have to live with threats almost on a daily basis. “I was sitting in the office of a senior police officer for an interview. A local journalist called him for a quote and the officer responded back saying, “Aisa mat samjhiye ki main aap ki stories nahi dekh raha hoon. Thoda sambhal ke kaam kijiye (Don’t presume I don’t know what stories you have been doing. Do watch what you write),” he said.

Altaf Qadri, a senior photojournalist from Kashmir who works with Associated Press, advocated the need of an independent photojournalists’ association in Kashmir. Giving an example of NIA’s arrest of Kamran, he said, “The criminal silence of the organization he [Kamran] worked for is unfortunate. If we had a strong association of photojournalists in Kashmir, things would have turned out differently.”

Many young photojournalists News18 spoke to said news organizations prefer not to hire them and instead use them as freelancers, leaving them to fend for themselves in this turbulence. “We shouldn’t allow ourselves to be exploited so that in times of crises we aren’t disowned by the organizations that we work for,” Dar said.

Qadri says freelance photojournalists live off whatever they are able to sell. “We have no insurance coverage; journalist bodies speak for full-timers, ignoring the freelancers.”

Beyond physical violence and frequent threats, photojournalists in the valley are also exposed to mental trauma after witnessing blood and gore on a daily basis. A photojournalist from North Kashmir said, “After spending days on work, you become so cold, so distant from reality that it’s hard to come out of the shock and the trauma. But we continue to tell the stories.”

(Part 3 of 12-part #KashmirBeyondCliches series)

Comments

0 comment