views

Measuring the Dew Point

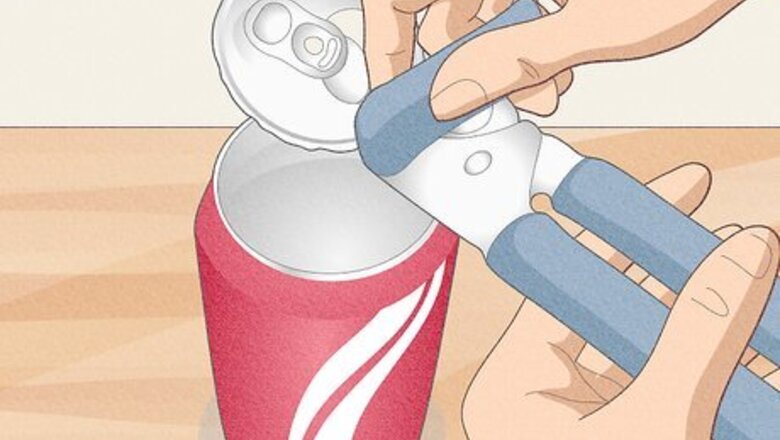

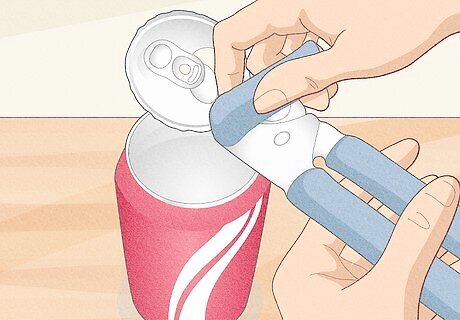

Cut off the top of an empty metal soda can with a can opener. Clamp the jaws of the can opener over the ridge at the top of the can, then turn the levered wheel to cut all the way around and through the can’s top. You’ll end up with a clean, smooth cut. It’s also possible to cut off the top of a can by poking through the side of the can with a sharp object (like a nail), then cutting through the can near the top with scissors. This creates a jagged edge, however, so be extra careful! A metal soda can is ideal for this experiment because the thin metal material rapidly conducts heat and matches the temperature of the water inside it.

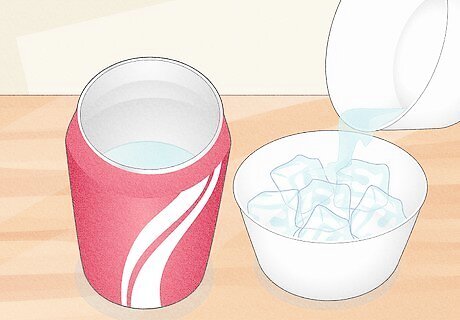

Fill the can halfway with lukewarm water. Run the hot water tap until the water feels slightly above the current air temperature, then add it to the can. If you only have cool water available, leave it in the can for 1 hour so it can warm to match the air temperature. Wipe away any condensation that may have formed on the outside of the can during the waiting time. If you splash any water on the outside of the can while filling it, wipe it off with a paper towel.

Fill a separate cup with ice and water. This can be any type of cup. Fill it 2/3 of the way with ice cubes, then add chilled water until the cup is filled nearly to the top. Use a spoon to stir the ice into the water for 30-60 seconds. Stirring the ice helps to chill the water further.

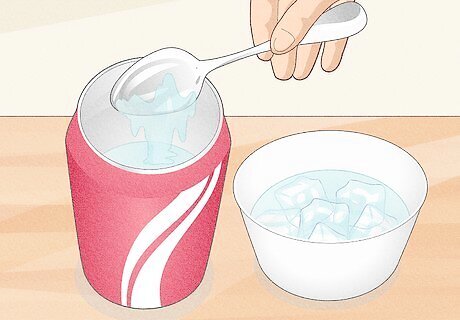

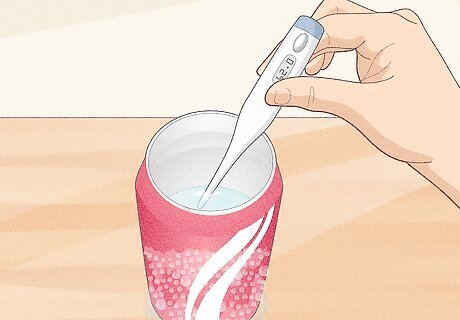

Slowly spoon and stir the ice water into the can. Scoop up one spoonful of the ice water—but not any of the ice cubes—and transfer it to the can. Stir the water in the can for 30-60 seconds before adding another spoonful of ice water. Keep repeating the process until you see condensation form on the outside of the can. Work slowly so that the can itself cools to the same temperature as the water inside it.

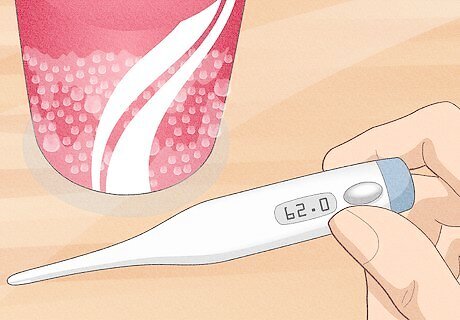

Check the water temperature as soon as condensation forms. As soon as you see moisture clinging to the outside of the can, stop stirring in ice water. Grab a thermometer and stick it into the water. The reading you get is the current dew point. The dew point—the temperature at which water condensation occurs—is determined primarily by the air temperature and the relative humidity. Relative humidity tells you how much moisture is in the air in comparison to how much moisture could be in the air. For instance, 75% relative humidity tells you that the air is holding 75% of the moisture it could possibly hold at its current temperature (warm air can hold more moisture than cold air).

Use your dew point finding to establish when condensation will happen. Based on your test result, you can make the following prediction: "Under the current temperature and humidity conditions, any material that is at or below the current dew point of X degrees will experience condensation." For example, if your experiment revealed the current dew point to be 62 °F (17 °C), you could state that any surface at or below that temperature would experience condensation. Keep in mind that the dew point constantly adjusts based on changes in temperature and humidity levels. The dew point right now may not be the same as the dew point in 1 hour!

Calculating the Dew Point

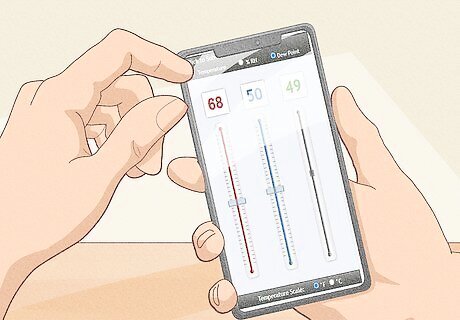

Use an online dew point calculator for quick results. Simply search online for “dew point calculator” and select one that comes from a reputable meteorological, scientific, academic, or building trade organization. Punch in the air temperature and the relative humidity and you’ll have the dew point right away! Use a thermometer to get the current air temperature, and a hygrometer to determine the current relative humidity. It’s also possible to build your own hygrometer!

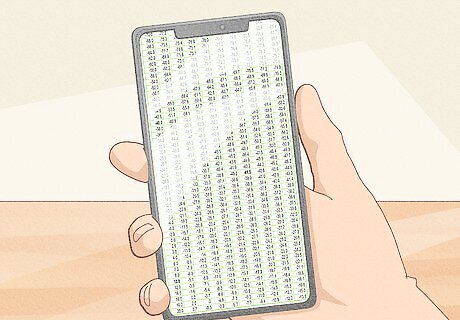

Refer to a dew point table to see a range of possibilities. Simply search online for a “dew point table” from a reputable source. One axis of the chart shows relative humidity levels, and the other shows temperature levels, both typically in 5 percent/degree increments. The figures in the middle of the chart show the dew point at particular temperature and humidity combinations. For instance, a temperature of 60 °F (16 °C) and a relative humidity of 60% results in a dew point of 46 °F (8 °C). Note that these results may slightly vary from chart to chart, or compared to a dew point calculator.

Consult a psychrometric chart if you can decipher it. If you think the name “psychrometric” is hard to figure out, wait until you see the chart! Psychrometric charts definitely aren’t designed for novices, but they do provide a huge amount of data on atmospheric conditions, including dew point. Find a chart from a reliable source and read the instructions on using it carefully—and maybe read them twice! For an example of a psychrometric chart, check out a source like the following: https://extension.psu.edu/psychrometric-chart-use In general terms, the curved line that sweeps from the bottom left to the top right of the chart represents the dew point. But getting the actual data is a bit more complex than that.

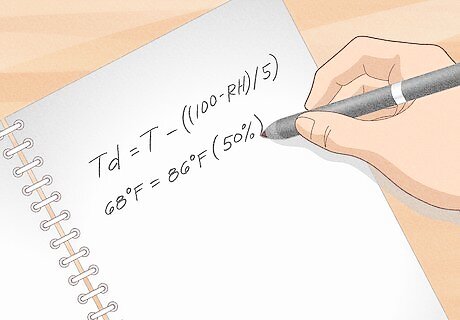

Solve an approximate or precise dew point formula if needed. If the relative humidity is over 50% and you don’t need a precise calculation, try this simplified formula: Td = T - ((100 - RH)/5). In this formula, Td is the dew point, T is the air temperature (in Celsius), and RH is the relative humidity. For example, if the temperature is 30 °C (86 °F) and the relative humidity is 50%, the dew point is roughly 20 °C (68 °F). The formula for precisely calculating the dew point is substantially more complicated. Consult the following website or a similar resource: https://iridl.ldeo.columbia.edu/dochelp/QA/Basic/dewpoint.html

Predict condensation on items at or below the dew point. Once you know the current dew point, you can accurately predict if and where condensation will occur. So long as the current air temperature and humidity levels stay the same, you can expect to see condensation form wherever the temperature is at or below the dew point. Predicting condensation seems simple, but keep in mind that the dew point is a moving target! Every change in air temperature and/or relative humidity impacts the current dew point. So, your condensation prediction right now may not be accurate an hour from now!

Preventing Condensation Indoors

Seal off cold air entry points where condensation is likely to occur. Any cold air that comes in through cracks or holes causes nearby surfaces to reach the dew point, resulting in condensation. Filling cracks and holes with caulk and other sealing materials can therefore reduce condensation. Indoor condensation often happens around windows and doors during cold weather. This moisture can ruin finishes, cause rot, and create mold.

Insulate walls, doors, windows, and other surfaces in the area. Adding insulation to an exterior wall can greatly reduce the amount of cold penetration. Likewise, installing insulated doors and windows helps to keep the cold air out. Insulated windows, for example, are far less likely to experience condensation than older, single-pane windows. Don’t try to insulate a drafty old window by closing a thick curtain over it. The moisture will simply collect behind the curtain, potentially causing rot and mold formation.

Pull moist air from condensation-prone areas with exhaust ventilation. Exhaust ventilation is especially important in bathrooms and kitchens. Reducing the indoor humidity level reduces the dew point, making it less likely that condensation will occur on indoor surfaces. For example, at 68 °F (20 °C) and 55% relative humidity, the dew point is roughly 51 °F (11 °C). At the same temperature with 40% relative humidity, the dew point is 43 °F (6 °C). Use properly-installed exhaust fans to pull moist air outdoors. Passive ventilation systems—like cracking open a window—will just cause more condensation in that area.

Run a dehumidifier to reduce air moisture in condensation areas. This works on the same principle as utilizing an exhaust fan—pulling moisture from the indoor air reduces the dew point, which in turn reduces the likelihood of condensation. During cold winter weather, an indoor humidity of 30%-40% is relatively comfortable and helps limit condensation. You might place a plug-in dehumidifier near a problem spot, or invest in a whole-home dehumidifier that works through your HVAC system.

Comments

0 comment