views

“Bantis zōbrie issa se ossyngnoti lēdys.”

The night is dark, and full of terrors. After 70 television episodes and a long, long night, Game of Thrones stands at the cusp of the final judgement of the Iron Throne’s true king. Set in eras long gone by, a part of Game of Thrones’ fictional docu-history format lies with the languages that its characters natively speak. The most notable of the two fictional or constructed languages, Dothraki and Valyrian, are mesmerising, for they hardly seem languages that did not exist before. From eccentric nuances of pronunciation, to grammatical complications, the languages bear the weight of the periods that they are based in.

Incidentally, while Dothraki and Valyrian might be two of the most popular and realistic constructed languages of all time, their creator is hardly new to the art. David J. Peterson, who has risen to stardom through two of Game of Thrones’ most impactful tongues, has practiced the science of constructed, artificial languages for years now. From the medieval Verbis Diabolo in Penny Dreadful, Nelvayu in Doctor Strange, Bodzvokhan in Netflix’s Bright, and Shivaisith in Thor: The Dark World, Peterson has specialised in creating languages for quite some time now.

A chance obsession

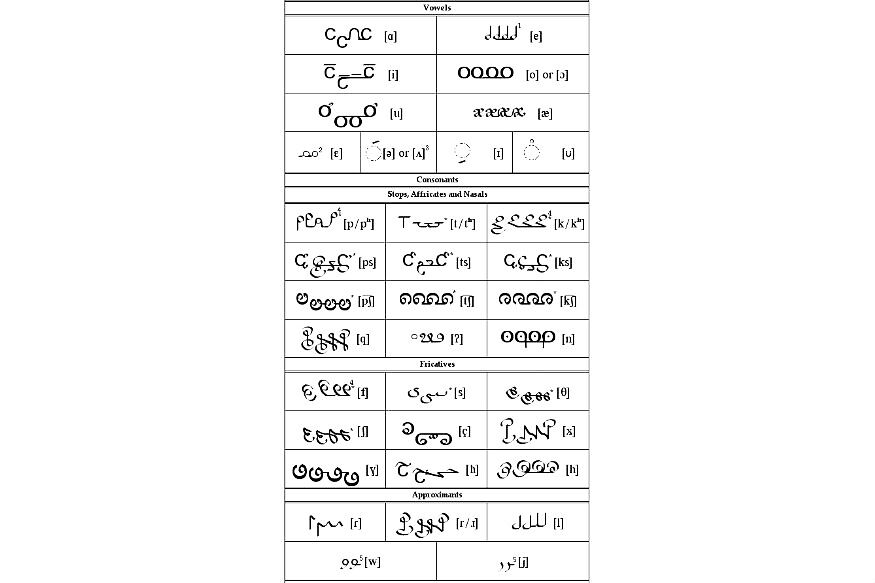

In 2000, Peterson had gotten obsessed with Esperanto, a constructed language that actually has the biggest active following in the world. In his old website that looks visibly late-’90s and wonderfully nostalgia-stricken, Peterson explains his very first obsession with constructed languages, or conlang, “One day, during a phonetics lecture in Prof. Mchombo's class, I was writing in Arabic (a hobby), when I thought to create an Arabic-style IPA. As I was doing that, though, I took a further bodhi tree leap and thought, "What if I create my own language that was like Arabic and Esperanto mixed together?" At that point, the lecture was over, and I started working on the script that would later become the Megdevi script.”

Peterson was, in fact, admittedly more interested in the orthography, as some of his earliest works state. Today, he is a veteran that gave us our Khaleesi — a name that, according to the United States Social Security Administration became more popular than Brittany in 2017 itself. Conversing with us in the middle of a presumably busy week, Peterson says, “I began creating languages in 2000, but I didn't get pretty good till around 2006. If you look at those languages, I think it's a fair representation of the work I did from 2000-2003. My first ever language (was) Megdevi, (and) naturally, the first languages I created were not very good. I began to get better when I studied the work of other language creators in the language creation community.”

Building a language

It is at this point that Peterson started working on vowel harmonies and elaborate phonology, some of his earliest experiments coming in with his earliest works. Today, Peterson follows a very open way of working on the languages that he creates. “I don't use natural languages as models, it's not necessary. There's no right or wrong way to begin — if I'm creating a spoken language, I begin by creating the sound system. I feel better knowing that that's in place before moving on to the grammar,” he says

Comments

0 comment