views

The recent attempt by the Chinese Army to grab Indian territory in Arunachal Pradesh and the befitting reply given by the Indian Army has stoked a new controversy in the domestic politics of India. There has been a desperate attempt by the Congress to corner the Modi government on its China policy and especially the recent incident.

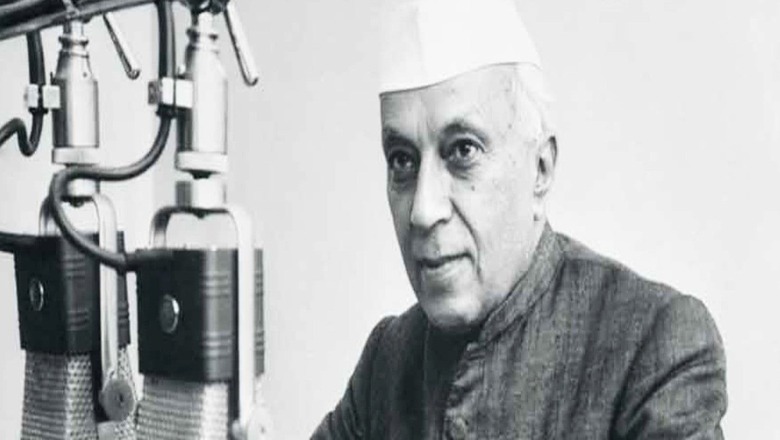

Nothing could be more ironic than this as India has been put strategically in a difficult situation vis-à-vis China, courtesy the blunders of the Nehruvian era. The first Prime Minister of independent India Jawaharlal Nehru’s myopic view of China led the latter to gobble up Tibet which was a strategically significant buffer zone between India and China. Basking in the self-glory of being a global leader, Nehru handed Tibet on a platter to China. This has resulted in making Indian borders extremely vulnerable to Chinese transgressions.

Nehru vs Patel on Tibet

In wake of the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950 that dramatically altered the geopolitics of the region, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister of India, wrote to Nehru a month before his death, “We have to consider what the new situation now faces us as a result of the disappearance of Tibet, as we know it, and the expansion of China up to our gates. Throughout history, we have seldom been worried about our northeast frontier. The Himalayas have been regarded as an impenetrable barrier against threats from the north. We had a friendly Tibet which gave us no trouble. The Chinese were divided. They had their own domestic problems and never bothered us about our frontiers.”

Bertil Lintner writes in China’s India War: Collision Course on the Roof of the World, one of the most authentic works on the Sino-Indian relationship in the 1950s, “Nehru, who failed to understand the mindset of Beijing’s new communist rulers, continued to believe in friendship with China. India and China, in his view, were both countries which had risen from repression and should work together with all the newly liberated countries in Asia and Africa.”

Former foreign secretary of India Shyam Saran says aptly in his recent book, How China Sees India and the World, “Nehru adopted what proved to be an unusually myopic view concerning China’s occupation of Tibet.” He continues, “From the Nehru papers accessed recently by a few scholars, Nehru had this to say about China and Tibet: Whatever may be the ultimate fate of Tibet in relation to China, I think there is no practically no chance of any military danger arising from any possible change in Tibet. Geographically this is very difficult and practically, it would be a foolish adventure. If India is to be influenced or an attempt made to bring pressure on her, Tibet is not the route for it.”

“The ‘foolish adventure’ became a reality within the space of just a few years, with China’s border war with India in 1962,” writes Saran. And such foolish adventures have been happening repeatedly primarily because China controls Tibet. What we have witnessed in Arunachal Pradesh recently is also what Nehru had termed a ‘foolish adventure’ but in reality that has become a major threat to India’s territorial integrity. Had Nehru not acted on his myopic view, the geostrategic position in this region would have been vastly different!

Ignoring Tibet’s call for help

Francine R Frankel has given a shocking account of how Nehru overlooked the desperate calls by Tibet for its help after the Chinese invaded it in his seminal work on Nehru’s foreign policy titled When Nehru looked East. Frankel writes, “The last desperate efforts made by the Tibetans to hold on to their de facto independence by appealing to Britain, Canada and the United States for help in the United Nations, also floundered on lack of support from India.”

“(In fact) India refused to sponsor Tibet’s appeal in the United Nations, ultimately introduced by El Salvador. India did not (even) second the Tibetan resolution in the United Nations and instructed the Indian representatives to assert that a chance for a peaceful settlement still existed and that the UN could facilitate a negotiated solution by not putting Tibet’s appeal on its agenda. Further efforts to get Tibet a hearing in the General Assembly, in early January 1951 failed to elicit a response from… India.”

Earlier fearing a Chinese invasion, Tibet had approached India at the end of 1949 seeking help for recognising it as an independent country in the United Nations. But Nehru did not act. In fact, while the Chinese had no legitimate claim over Tibet, India had inherited significant rights from the treaty between British India and Tibet in 1914. The position of the advantage granted to India in Tibet by this treaty was surrendered meekly by Nehru. India had a full-fledged Mission there and a strong official presence with military posts also. In the 1950s India surrendered all these positions.

Nehruvian Blunder in 1952

One of the biggest blunders committed by Nehru was to agree to a Chinese proposal in 1952 of converting India’s Mission in Lhasa (Tibet) to a Consulate General. This Mission was the outcome of the India-Tibet treaty, commonly known as Simla agreement of 1914. The Chinese had never accepted this agreement. But as Tibet was an autonomous region, so China didn’t have any locus standi to object to this agreement. The communist regime that took over China in 1949 termed all earlier treaties including this one as unequal treaties. The Simla agreement had also defined the Sino-Indian border called the McMahon Line. But the Chinese communist regime refused to accept this border, also creating a major border dispute.

Thus, Nehru’s decision to convert India’s Mission to the consulate general in Tibet had wider ramifications. Vijay Gokhale, former Foreign Secretary and a well-known China expert, has analysed the significance of Nehru’s blunder in this regard in his latest book, The Long Game: How the Chinese Negotiate with India. “After receiving India’s written confirmation on the matter, the Chinese also quickly informed India that they had established an Assistant for Foreign Affairs in Lhasa and that henceforth the new Indian consulate general should deal with Tibet only through his new office. In accepting… (Chinese) proposals, India had agreed to three things. First, by accepting the principle that the earlier treaties were unequal, India had acquiesced in undermining the legal basis for all its privileges in Tibet as well as the Simla Agreement of 1914. Second, by converting the Lhasa Mission into a Consulate General, and giving a reciprocal facility to China in Bombay, it had changed the status of its relationship with the Tibetan government from a political relationship to a consular one. By inference, this also meant that India had accepted that Tibet was a part of the People’s Republic of China. And third, by agreeing to contact Tibetan authorities only through Chinese intermediaries in Lhasa, India had surrendered its right to have direct dealings with the Tibetan administration. This showed the methodical and practical nature of China’s negotiating strategy and tactics; China had done serious research on the treaties and other materials in possession of the Tibetan government about Indian interests in Tibet and devised a negotiating plan. The Government of India, on the other hand, went about the negotiations in an ad hoc fashion and without adequate internal consultation, left the proper research on facts.”

Instead of supporting Tibet, Nehru favoured China. Under Nehru, India became the first non-socialist bloc country to recognise the Chinese Communist regime after it snatched power in 1949 from nationalists in China. Within days of this recognition which provided legitimacy to the dictatorial rule in China, the Chinese Communist Party announced its intent to invade Tibet and within the next few months, it did that.

While all these developments were taking place instead of protecting Indian interests, Nehru was busy with pushing for making communist China a member of the United Nations. Further, in a 1954 agreement, Nehru conceded all Indian positions in Tibet and gave China the geostrategic leverage that has made Sino-Indian borders much more vulnerable for India than they were in pre-Nehru era.

The writer, an author and columnist, has written several books. He tweets @ArunAnandLive. Views expressed are personal.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment