views

Social ostracism and lack of opportunities have forced generations of lower caste families to continue indulging in manual scavenging as their daily job.

Not often discussed in mainstream media, however, is that over 95 percent of India’s 1.3 million manual scavengers are women. In spite of such overwhelming numbers and enough evidence pointing to serious health consequences directly resulting from this kind of work, government authorities have failed to implement available laws and programmes. Manual scavenging is a degrading profession and it needs solutions that are technologically pertinent, economically driven, socially responsible, and sensitive.

Manual scavengers remove untreated human excreta from toilets with bare hands and without any safety gear. Most manual scavengers belong to the Dalit community, and it is fairly evident that manual scavenging is often forced upon the community by the rigid and hierarchical caste system.

Health risks

Since manual scavengers do not use protective gear and work in extremely unhygienic conditions, they are relentlessly exposed to harmful gases such as hydrogen sulphide and methane, often resulting in respiratory illnesses, and cardiovascular and musculoskeletal disorders. They also suffer from skin problems such as psoriasis. Carbon monoxide poisoning, diarrhoea, nausea and tuberculosis are some of the other health problems faced by manual scavengers. According to Safai Karamchari Andolan (SKA) data, most women manual scavengers have an average lifespan of only 40-45 years due to a combination of health issues.

Are we in denial?

Manual scavenging is a reality, so are the associated deaths. There is, however, societal denial. Take the government’s statement to Parliament in August 2021 where it said there were no manual scavenging deaths documented despite records indicating that there were 941 deaths recorded while cleaning septic and sewer tanks. A similar denial can also be seen in the Swachh Bharat Mission which has come under fire for allegedly increasing the number of toilets that need to be manually cleaned.

The burden on women

Women face the triple burden of class, caste and gender. Close to 85 percent of female scavengers are married and receive monthly wages of just Rs 10 to Rs 20, according to a 2014 study that polled almost 500 women from Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. Sometimes they don’t even get compensated. Most of the time, daughters-in-law are expected to take over their mothers-in-law’s duties of cleaning faeces from public and private latrines. If they refuse, either out of regard for their own dignity and self-respect or in an effort to find alternate sources of income (which is even unusual because their options are scarce), they are shunned and treated with contempt.

Moving away from SDGs

Manual scavenging is preventing India meeting its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. They include Goal 8 of decent work and economic growth (absence of safety gear and equipment, not even minimum pay or any employment benefit) and Goal 6 of clean water and sanitation. In addition to these, the practice runs against Goal 10, that is, reduced inequality; Goal 16 of peace, justice, and strong institutions, as well as the Goal of gender equality.

Policies and programmes are failing

The primary reason for policies and programmes failing is the failure to take into account the social determinants of the occupation.

Most of these schemes have been aimed at male workers rather than women who constitute over 95 percent of the manual scavenging workforce. Moreover, since health is a state subject in India, it is almost impossible for the Union government to regulate implementation of laws already in place.

Additionally, certain initiatives such as the ‘Scholarship for the Children of Families Involved in Incline Occupations’, have had the reverse effect — encouraging people to remain in their occupations. Other reasons include lack of social awareness, lack of alternative job opportunities and no clarity leading to poor implementation of penalties for non-enforcement of the law.

Recommendations

Interventions have to be political, social, technological, economic and, the most important, humane.

● It is important to rehabilitate the people and reintegrate them into the mainstream of society. After the Supreme Court had to intervene in 2014 ordering all states and Union Territories to record all manual scavengers and rehabilitate them, some progress has been made. However, a lot remains to be done on various fronts, such as skill enhancement, one-time cash assistance and capital funding for encouraging self-employment projects.

● To rehabilitate children of manual scavengers, it is important that they are given quality education, thereby preventing the future generation from getting into the practice.

● The Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act was implemented in 1993. Later, in 2013, the Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act was passed. Once again, implementation has been lax. On several occasions, government authorities have refused to speak on the issue and continue to practise silence. There are no strict regulations for punishing offenders. Therefore, the oppression continues.

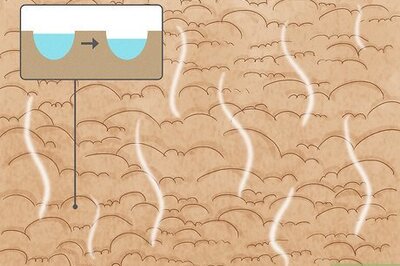

● The government is committed to constructing restrooms utilising “twin-pit” technology as part of the Swachh Bharat initiative, which purportedly would eliminate a person’s direct contact with human waste. However, only 15 percent of the toilets built under this programme used this technology. The issue can be greatly resolved if technology is applied effectively.

● Cesspit waste can be converted through certain processes into useful manure for farming. Trucks equipped with pumping devices that can clean up to seven cesspits per day are already in use in several parts of India. If appropriately used, these techniques can assist in removing several individuals from the dangerous practice. However, ensuring that this does not result in the dumping of untreated sewage into aquatic bodies is crucial.

● Last but not the least, it is vital that the general public is informed of the legal repercussions associated with the employment of manual scavenging. Workers should be aware of their rights and the law in order to prevent exploitation.

The deep-rooted normalisation of caste-based “purity” has somehow failed the century-long fight of attempting to get away with manual scavenging. Over 1.3 million people step out of their homes every day risking their lives to earn the lowest wages. Over the years, governments have made several efforts to work towards cleaner and healthier India but the caste prejudice and the consequent discrimination have not been specifically addressed. It is time that we do so.

Mahek Nankani is Assistant Programme Manager, The Takshashila Institution. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment