views

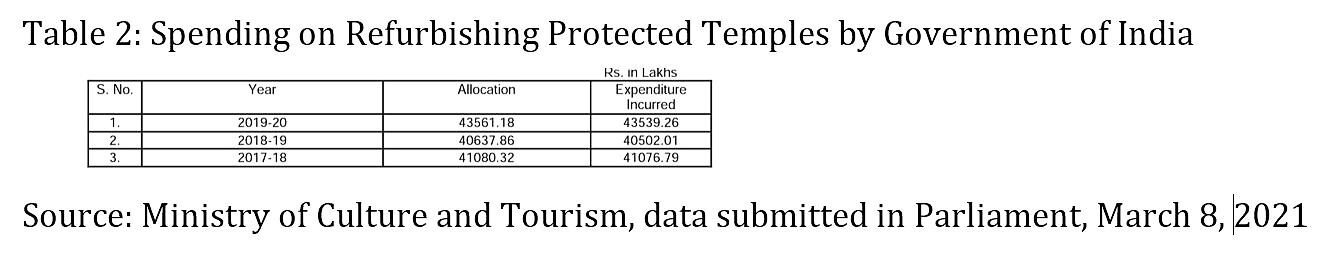

His forehead painted yellow with the mark of Shiva — sandalwood, bhasm (ash), turmeric and vermillion — a saffron scarf over his shoulders and a Rudraksha mala (another symbol associated with Shiva), Prime Minister Narendra Modi presided over yet another major temple renovation in the ancient city of Ujjain last week.

Chanting the Saivite devotional cries of ‘Har Har Mahadev’ and ‘Jai Sri Mahakal’ before a crowd of devotees, the prime minister framed the inauguration of the Mahakal Lok corridor at Ujjain’s Mahakaleshwar temple, which houses one of India’s 12 jyotirlinga sites (considered a manifestation of Shiva), in epochal terms. “This development of our jyotirlings,” said Modi, “is the development of the spiritual flame of India. It is the development of India’s knowledge and its darshan.” This “cultural darshan” of India, he emphasised, “is once again reaching the peak and getting ready to guide the world”.

It would be a mistake to see the corridor project at the Mahakaleshwar temple in what was once the ancient Hindu kingdom of Avantika in isolation. It is part of a concerted strategy that combines religiosity, cultural identity and Hindu-ness with a new unapologetic cultural nationalism that is deeply rooted in Hindu cultural symbols. This cultural play reaches out to many religious Hindus beyond the BJP’s core group of Hindutva supporters.

Many liberals make the mistake of dismissing the carefully choreographed symbolism of Modi presiding over the refurbishment of ancient religious sites, such as the Kashi Vishwanath temple in Varanasi last year, as mere political optics aimed at short-term electoral mobilisation. They could not be more wrong.

In fact, the cultural power play and Modi’s focus on refurbishing temples are deeply intertwined with the idea of ‘New India’ itself that the PM heralds as a radical break with the past. Beyond symbolism and the reordering of ritual economies and cultures, it carries within it a much deeper remaking of the political economy as well, with an underlying economic design focused on a new kind of Indian consumer and citizen.

There are five key features that characterise this shift:

The Modi-Nehru contrast: Modi’s fronting of many of these temple projects — such as the Kashi Vishwanath corridor which he inaugurated in 2021 and the radical symbolism of the PM presiding over the Bhoomi-pujan of the Ramjanmabhoomi in Ayodhya in August 2020 — can be directly contrasted with Nehru’s firm opposition to the state playing any role in reconstructing the Somnath temple in 1951.

His intense debates with KM Munshi, the minister in his cabinet who spearheaded that initiative, and his insistence that Rajendra Prasad, India’s first president, attend the Somnath ceremony in his personal capacity, not as the Republic’s first citizen, set a template for a newly independent country that had just been partitioned on religious lines.

Importantly, Nehru’s opposition to the government rebuilding temples — as opposed to his famous positioning of dams as the “temples of modern India” — was framed in a state that, at least constitutionally, was not yet ‘secular’. The words ‘secular’ and ‘socialist’ were added to the Preamble by Indira Gandhi in 1976 during the Emergency through the Forty-second Constitutional Amendment.

Modi’s personal fronting of temple projects stands out in sharp contrast. On June 18, 2022, for example, PM Modi unfurled a flag atop the refurbished Kalika Mata temple in Gujarat’s Pavagadh Hills. This was after the ‘shikhara’ or spire of the 11th century temple — which was destroyed in an attack in the 15th century Gujjarat Sultan Mahmud Begada during his invasion of Champaner — was restored as part of a redevelopment plan. “Today’s moment fills my heart with special joy,” said the Prime Minister after unfurling the flag. “You can imagine that the flag was not hoisted on the summit of Maa Kali till after five centuries and even after 75 years of independence… Today the flag is once again hoisted on the summit in the Pavagadh temple after centuries….It is also a symbol of the fact that centuries change, eras change, but the peak of faith remains eternal.”

Connecting the dots between that particular project’s redevelopment and other large temple projects across the country, PM Modi added, “You must have seen the grand Ram Temple taking shape in Ayodhya. Be it Vishwanath Dham in Kashi or Kedar Baba’s Dham, today the spiritual and cultural glory of India is being restored. Today, New India, along with its modern aspirations, is continuing with its ancient heritage and identity with the same zeal and enthusiasm and every Indian is proud of it. These spiritual places are becoming mediums of new possibilities along with our faith.”

Union Home Minister Amit Shah clearly underlined this theme in December 2021 when he told a public gathering in Ahmedabad: “For many years, the centres of faith of the Hindu community were left humiliated and nobody took the initiative to bring the glory back until Modi came to power at the Centre with a full majority… We have seen how earlier people would be ashamed of visiting a temple. But a new era began in the country after Narendrabhai performed ‘Ganga aarti’ after rubbing the ashes of Kashi Vishvanath following an invite by the President (to form the government at the Centre).”

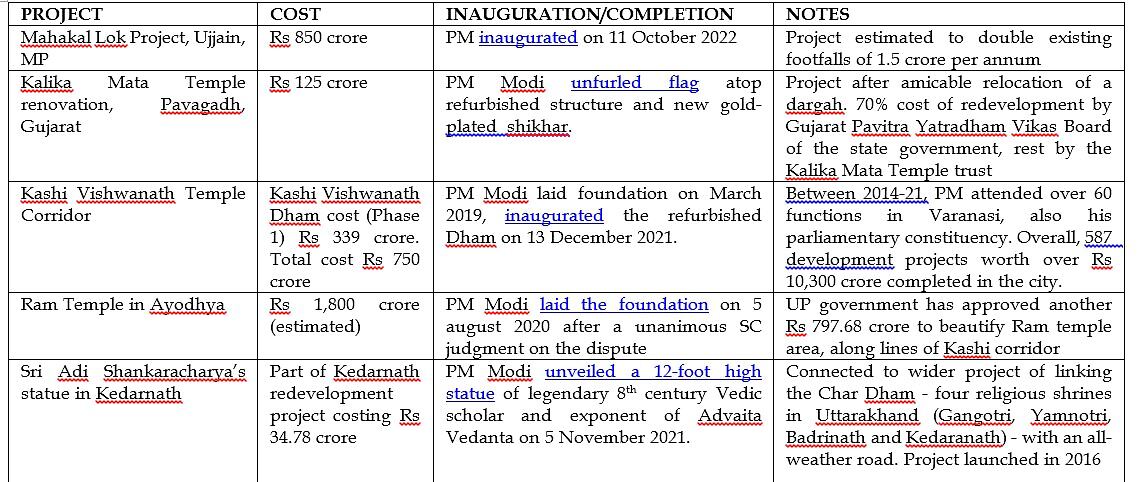

Temples, Domestic Religious Tourism and City Redevelopment Projects: The focus on temples is wide ranging — with a deep focus on infrastructure, development and domestic tourism as much as it is on cultural nationalism. A sampling of the PM’s focus on large-scale projects on religious sites is revealing (see Table 1)

Table 1: Temple Redevelopment Projects under Modi Government: 2014-2021

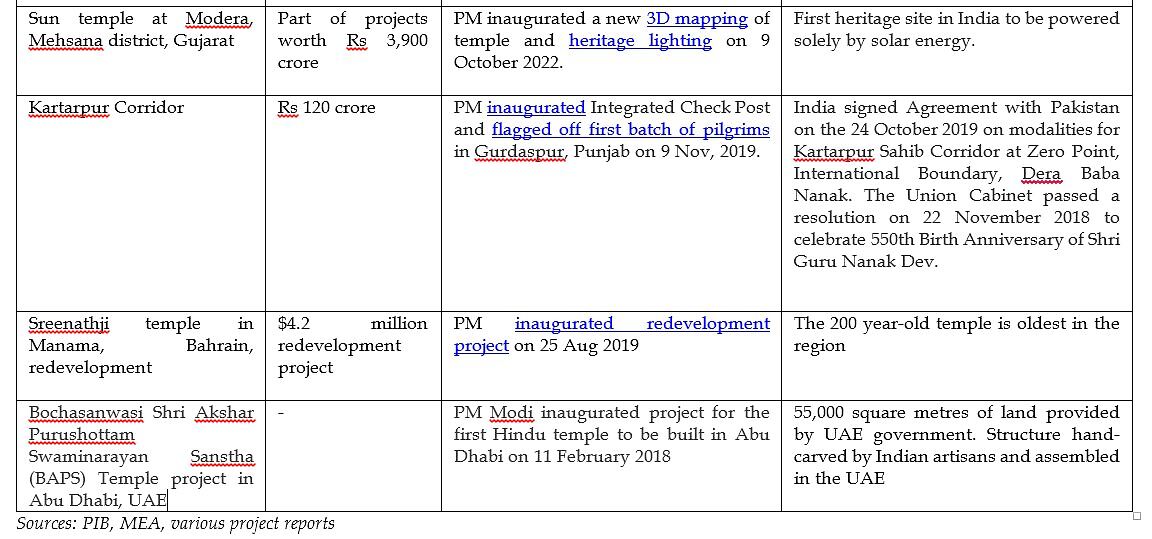

By way of background, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism informed Parliament in 2021 that it was spending about Rs 435.6 crore a year on maintenance and beautification of ancient temples (See Table 2).

The political strategy of using religious spectacles is also underpinned by the economic logic of religious tourism. Agra’s Taj Mahal has long been the global face of Indian tourism. However, UP government officials have asserted that while Agra consistently gets the highest number of foreign tourist arrivals in the state each year (over 2 million foreigners and 83.5 million Indians in 2019), the religious sites of Prayagraj (289.1 million because of the Kumbh that year, Ayodhya (over 30 million), Govardhan (16.9 million) and Vrindavan (16 million) consistently receive a substantially higher number of travellers, mostly domestic pilgrims.

In fact, Prayagraj, with its confluence of rivers considered holy by Hindus, continues to be the most popular city in UP for domestic tourists. Even in non-Kumbh Mela years, it draws a substantial number of tourists: 49.4 million in 2018, for instance. This is true of Ayodhya as well.

New Transport Links: Creating new transport linkages is a vital cog of this strategy, beyond the redevelopment of the sights themselves. Tourism numbers also underlay the Central government’s plans (currently under discussion) to eventually connect Delhi and Ayodhya via a high-speed bullet train (to run on high-speed rail corridors, which are, of course, Modi’s signature project, started with the Japanese government’s technical and financial support). Also on the anvil is connectivity for the religious sites of Mathura and Prayagraj, as well as Agra, on the proposed Delhi–Varanasi bullet train route.

At a national level, the 15 thematic circuits being developed as part of a New Swadesh Darshan Scheme include a Ramayana Circuit as well as a Buddhist Circuit. For example, IRCTC has launched the Sri Ramayana Express, a special tourist vegetarian train to take pilgrims to places associated with the Ramayana in 18 days.

At the state level, in UP for example, Yogi Adityanath, in his maiden state budget as chief minister during his first tenure, pushed to allocate Rs 1,240 crore towards developing the Ram, Krishna and Buddha tourism circuits in the state. In 2019–2020, his government allocated significant funds to this project — over Rs 300 crore to Ayodhya, over Rs 125 crore to UP Brij Tirtha (tourism for the Mathura–Vrindavan circuit) and over Rs 200 crore for roads leading up to the Kashi Vishwanath temple in Varanasi. Conceptually, these projects merge seamlessly with the state government’s declared aim of rebuilding Ayodhya as a ‘Vaishwik Nagri’ (global city), and with plans for an airport that would have air-routes to South Korea, Fiji, Japan, Nepal and Thailand.

Hindu-ness and Soft Power: Where China uses Mandarin and a host of cultural tools for its soft power projection, the BJP seeks to deploy the cultural power of Hinduism for India’s global branding. A good example of this is the Modi regime’s celebration of yoga, which is personally fronted by the prime minister, both nationally and internationally. It is not an accident that the BJP made much of the establishment of the International Yoga Day by the UN on December 14, 2014 – a few months after Modi came to power. The UN Resolution was proposed by PM Modi himself in an address during the opening of the 69th session of the General Assembly. ‘Yoga is an invaluable gift from our ancient tradition,’ he told the UN.

The idea of Hindu cultural power is an incipient concept still, but what these statements indicate is a visualisation of India powered by Hindu-ness and unapologetically. For the purveyors of ‘New India’ — a slogan formally adopted by the BJP in a political resolution on September 9, 2018 — such a country would overwhelmingly look to its Hindu traditions as markers of identity.

As the PM indicated in Ujjain, this cultural positioning is aimed at both a national and global audience. For example, even at the Ram Temple consecration ceremony in 2021, PM Modi, UP CM Yogi Adityanath and RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat all chose to dwell on why the message of the Ayodhya movement had ramifications far beyond India’s borders, saying it was the duty of the young to spread this message worldwide.

Speaking of the ‘New India’ under Modi, Bhagwat argued that ‘in the time of Corona’, the world was looking for answers. ‘Does anyone have answers?’ he asked. ‘The world has tried two methods [presumably capitalism and communism]. Is there a third way? Yes — we have a third way. This temple is just the beginning of the preparation of spreading that message of an alternative way.’ (Emphasis added.)

The contours of this third Indian way are not clearly spelt out, beyond homilies about Hindu tolerance and ancient wisdom-liners like ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam’ (The World is One Family) — themes that Modi and the RSS often refer to. Yet, they were hinting at deeper, more tantalising possibilities.

This was clearly a positioning of India as the fount of a Hindu civilisation as compared to, say, a Sinic/Chinese or Western civilisation. This concept may be a bit nebulous, as was the ‘Gandhian socialism’ of Deen Dayal Upadhyaya that the BJP had briefly adopted in the 1980s. It is, however, rooted in the civilisational notion of India as a Hindu power that is steeped in ‘parampara’, or tradition.

This is an India wielding the soft power of ancient Hindu practices, acting as a swing state—probably in the sense that Samuel Huntington meant it when he wrote The Clash of Civilizations. Huntington’s thesis, first fleshed out as an article in 1993, basically argued that the praxis of local politics would shift to the ‘politics of ethnicity’, while that of global politics would shift to the ‘politics of civilizations’.

In other words, ‘cultural entities’ would become the central dividing axes of power, locally and internationally: Sinic (Chinese), Islamic, Japanese, Orthodox (Russia), Western (Europe, North America, Australia, New Zealand), Latin American, African and Hindu (India). While this idea was severely critiqued for simplifying the complexity of international relations — such as the huge differences among Islamic states — its central thesis of essentialist ‘cultural’ norms acting as a powerful guiding force for states willing to use them is undeniable.

You do not have to agree with this formulation to see its ambition.

Architectural Reordering, ‘New India’ and Legacy: The temple projects, the reordering of the ritual economy and the explicit focus on cultural markers in this shift segue seamlessly into PM Modi’s other signature projects that reorder the visual geography of the nation. The new Central Vista in Delhi and the new Parliament building which is currently being constructed are all physical manifestations of the larger reordering of the nation that PM Modi heralds with his idea of ‘New India’.

This shift in India’s visual geography, in that sense, is long-term, systemic and intrinsically linked to an alternative conceptual idea of the nation that is fundamentally different from Nehru’s.

Read all the Latest Opinion News and Breaking News here

Comments

0 comment