views

With just a few days left for India to attempt its historic moon landing, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) has begun gearing up for its next big mission–the sun. While it took nearly 40 days to reach the moon, the space agency has charted out a four-month-long trajectory for its solar spacecraft set for launch next month.

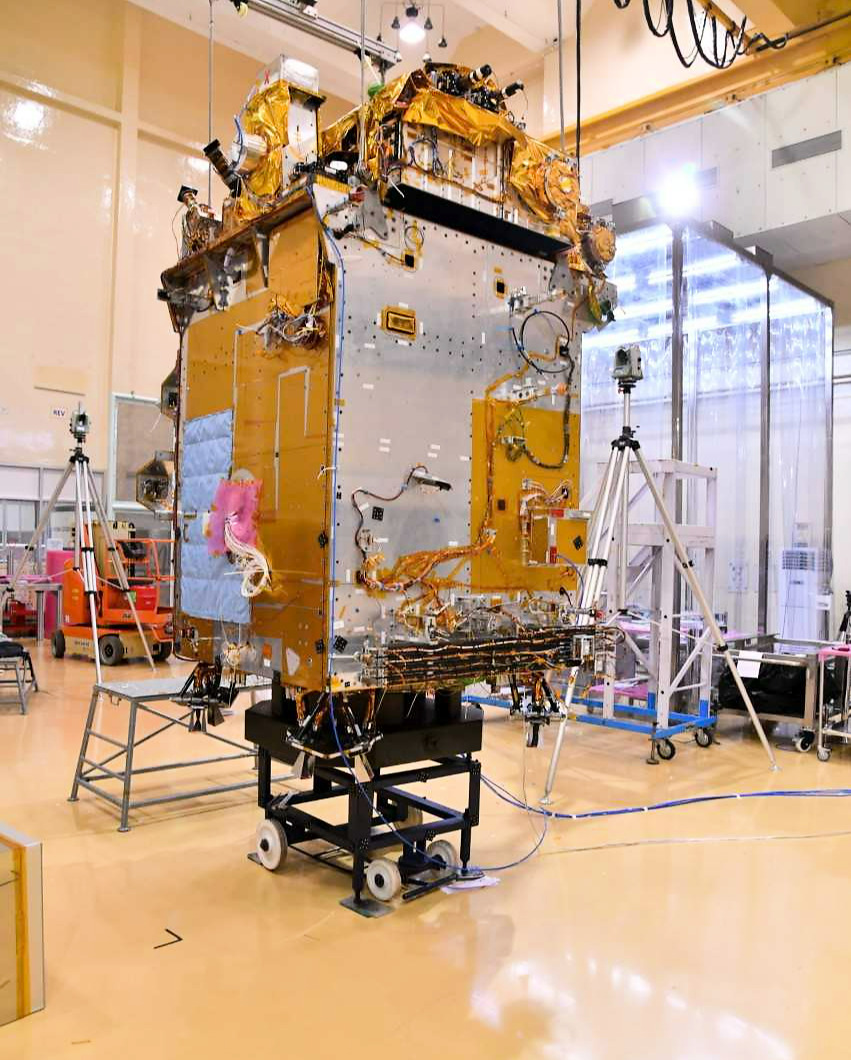

India’s first space-based observatory, Aditya-L1, has been in the pipeline for more than a decade now. Scientists at Bengaluru’s Indian Institute of Astrophysics had been painstakingly working to assemble its primary payload –a 90-kg Visible Line Emission Coronagraph (VERC) which will drive ISRO’s first-ever scientific mission to the sun. The final satellite consisting of seven different payloads has now been successfully integrated at UR Rao Satellite Centre (URSC), Bengaluru. On Monday, it was transported to Satish Dhawan Space Centre, Sriharikota for its launch next month aboard ISRO’s old warhorse–PSLV.

The rocket would ascend into space from Sriharikota and travel nearly 1.5 million kilometres towards the sun–almost three times the distance of Earth from its closest neighbour moon. Though the sun is about 150 million kilometres from the Earth, the spacecraft would be put into a halo orbit around the Lagrange point (L1)–1.5 million km from the Earth, so it can view the mighty sun without any eclipses.

Four-month-long journey

Like all interplanetary missions of ISRO, the spacecraft will initially be placed in a low-earth orbit. Subsequently, the orbit will be made more elliptical to propel the spacecraft towards the L1 point, so it exits the Earth’s gravitational sphere of influence. Once it exits, the spacecraft will be injected into a large halo orbit around L1. Overall, it will take about four months for the satellite to reach L1.

Due to the limitations of the rocket, only a limited set of instruments with a specific capacity have been chosen for the mission, which explains why it took scientists years to build the payloads. “For over 100 years, we have had the historic image of the sun, but it is the first time an instrument built by our scientists will be sent so close to it, that it can possibly capture what’s happening on it,” Professor Annapurni Subramaniam, director, IIA, Bengaluru, had previously told News18 in an exclusive interview.

What will scientists study?

Out of the seven payloads developed indigenously, four would carry out remote sensing of the sun, while three others are designed to conduct in-situ experiments. They will study the photons and the solar wind ions and electrons emitted by the sun, as well as the interplanetary magnetic field created in space.

The scientific mission will also look to gather more data on understanding the coronal mass ejection–the powerful radiation storms that erupt suddenly from the sun’s corona into space, and sometimes even reach the Earth.

Despite years of observations, there are no such tools available which can help scientists to predict these massive clouds of energy. Various spacecraft and communication systems are prone to such disturbances and therefore an early warning of such events is important for taking corrective measures beforehand.

The space scientists from across various institutes had held a meeting at ISRO headquarters in Bengaluru in June to deliberate upon all the final aspects of the two missions, following which they were given a go-ahead. If all goes as planned, the mission could take off next month from Sriharikota.

Comments

0 comment