views

New Delhi: Scientists at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Roorkee, may have cracked the treatment of chikungunya. On May 4, IIT’s biotechnology laboratory announced that they had identified a molecule that showed antiviral activity against the mosquito-borne disease.

Though the research is still in a nascent, pre-clinical stage, determining such a molecule paves the way for future work.

There are currently no drugs or vaccines for chikungunya, a viral disease, in the market. The IIT lab’s work began in 2006, said researcher Shailly Tomar, in the aftermath of the 2005-2006 outbreak of the disease, the first in recent decades.

The disease had started in the Reunion Islands in the Indian Ocean and soon spread to India, largely affecting states in south India. The second major outbreak was in 2016, when north India felt the brunt of the disease for the first time. This is when the IIT- Roorkee lab collaborated with local pathologies to collect samples of the virus.

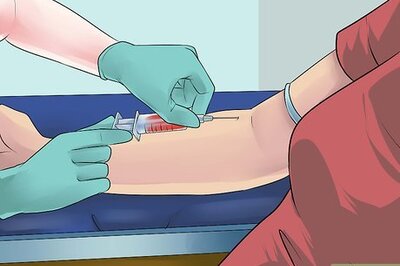

Tomar and her team took a page from the antiviral research done on HIV and Hepatitis C, where a molecule was developed to attack virus specific proteins not found in the host body. The molecule targets the nsP2 protease enzyme, resulting in the antiviral activity.

The researchers determined the three-dimensional structure of the protein and were able to see at the atomic level what it looks like, so as to better attack it. They identified 10 molecules, of which they selected the two best ones that could stop the enzyme activity.

In a lab, explained Tomar, the virus is added to cell lines to see how it propagates or multiplies itself. If it is added in the presence of an effective antiviral, she said, it should not propagate strongly. One of the molecules her team tested, Pep-1, showed remarkable antiviral activity.

In a concentration of 10 micromolarity of the Pep-1 compound, there was no virus propagation and in a concentration of 5 micromolarity there was 99 percent reduction.

However positive these steps are, a potential drug against chikungunya is still years away. The next step for Tomar and her team is to test the molecule in animal models, in mice. Depending on these results, interested pharmaceutical companies will take over to modify the molecule as needed, whether to make it more potent or more stable.

Pharma companies, pointed out Tomar, had the expertise that public institutions, even IITs lack. They know how to make formulations, the research required for clinical trials that Tomar, admitted would take her much longer to conduct.

With the monsoons looming, India is about to face its mosquito-borne disease season. Dengue has already reared its head. Though there are no reported cases of chikungunya, yet, it affected 940 people in India in 2017 and over 60,000 in 2016.

Comments

0 comment