views

London: The British judge who presided over the Da Vinci Code trial has put a code of his own into his judgment and said he would ''probably'' confirm it to the person who breaks it.

Since Judge Peter Smith delivered his judgment in the case on April 7, lawyers in London and New York have begun noticing odd italicizations in the 71-page document.

In the weeks afterward, would-be code-breakers got to work on deciphering the judge's code.

''I can't discuss the judgment,'' Smith said Wednesday in a brief conversation with the Associated Press, ''but I don't see why a judgment should not be a matter of fun.''

Italics are placed in strange spots: The first is found in paragraph one of the 360-paragraph long document. The letter S in the word claimants is italicized.

In the next graph, claimant is spelled ''claiMant,'' and so on.

The italicized letters in the first seven paragraphs spell out ''Smithy code,'' playing on the judge's name.

Lawyer Dan Tench, with the London firm Olswang, said he noticed the code when he spotted the striking italicized script in an online copy of the judgment.

''To encrypt a message in this manner, in a High Court judgment no less? It's out there,'' Tench said. ''I think he was getting into the spirit of the thing. It doesn't take away from the validity of the judgment. He was just having a bit of fun.''

Smith was arguably the highlight of the trial, with his sharp questions and witty observations making the sometimes dry testimony more lively. Though Smith on Wednesday refused to discuss the judgment or acknowledge outright that he'd inserted a secret code in its pages he said: ''They don't look like typos, do they?''

PAGE_BREAK

When asked if someone would break the code, Smith said: ''I don't know. It's not a difficult thing to do.'' And when asked if he would confirm a correct guess to an aspiring code-breaker, the High Court judge said, ''probably.''

Tench said the judge teasingly remarked that the code is a mixture of the italicized font code found in the book ''The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail'' _ whose authors were suing Dan Brown's publisher, Random House, for copyright infringement _ and the code found in Brown's ''The Da Vinci Code.''

Authors Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh had sued Random House Inc., claiming Brown's best-selling novel “appropriated the architecture” of their 1982 nonfiction book, The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail.

Both books explore theories that Jesus married Mary Magdalene, the couple had a child and the bloodline survives, ideas dismissed by most historians and theologians.

Since the judgment was handed down three weeks ago, Tench said it took several weeks _ and several watchful eyes _ to spot the code. Now, London and New York attorneys are scrambling to decode the judgment.

''I think it has caught the particular imagination of Americans,'' Tench said. ''To have a British, staid High Court judge encrypt a judgment in this manner, it's jolly fun.''

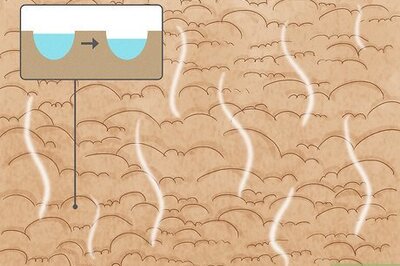

After the ''Smithy Code'' series, there are an additional 25 jumbled letters contained on the first 14 pages of the document, Tench said, adding he thinks the series can be decoded using an anagram or an alphabet-inspired, code-breaking device. Known as a codex, the system is also found in Brown's ''The Da Vinci Code.''

A codex uses the letters of the alphabet and matches them with an additional set of letters placed in a different order, dubbed a substitution cipher. It is derived from a scene in the novel where Harvard professor Robert Langdon and French cryptographer Sophie Neveu use the code to try to unravel the location of the Holy Grail, using a famed device invented by Leonardo DaVinci for transporting secret messages.

PAGE_BREAK

I'm definitely going to try to break the code,'' said attorney Mark Stephens, when learning of its existence.

''Judges have been known to write very sophisticated and amusing judgments,'' said Stephens, a lawyer specializing in media law and copyright issues. ''This trend started long ago ... one did a judgment in rhyme. Another in couplets. There has been precedent for this.

''It adds a bit of fun to what might have been a dusty text,'' he said.

Comments

0 comment