views

New Delhi: In a strongly-worded verdict, the Allahabad High Court came down heavily on a trial court judge for being "unmindful of the basic tenets of law" while convicting Rajesh and Nupur Talwar of double murder, in the 2008 Aarushi Talwar murder case. While exonerating the dentist couple of all charges, the division bench reproached CBI judge S Lal for acting like a "film director" who tried to solve the case like a "mathematical puzzle".

The HC minced no words, and rightly so because the guiding principle of the criminal jurisprudence in India has always been that let 100 guilty men escape punishment than one innocent be damned. The rules of procedure and evidence obligate all courts that presumption of innocence is not encroached upon and interpretation of law and evidence has to be in a manner which favours the accused.

The HC felt that in the Aarushi case, the trial judge lost sight of this golden principle along with a body of Supreme Court judgments that has authoritatively ruled that it will always remain the prosecution's duty to prove its case beyond all reasonable doubts and in no situation can this burden be shifted entirely on the accused.

Undoubtedly, the higher court is well within its rights to comment on the merits of a case in appeal and to some extent, speak on the manner in which trial judges decide cases. Power of a superior court under the Indian legal system cannot be undermined and they must keep a constant vigil over the justice delivery system as well.

It will perhaps be unfair if no thought is spared to the principle of “judicial fearlessness and independence” – as elucidated by the Supreme Court and the spectrum of reasons on how and why trial judges could err in high-profile cases. In more often than not, the trial court judgments have been interfered with by the higher courts, and thus the Aarushi Talwar murder case is not a rarity.

Take these case for example:

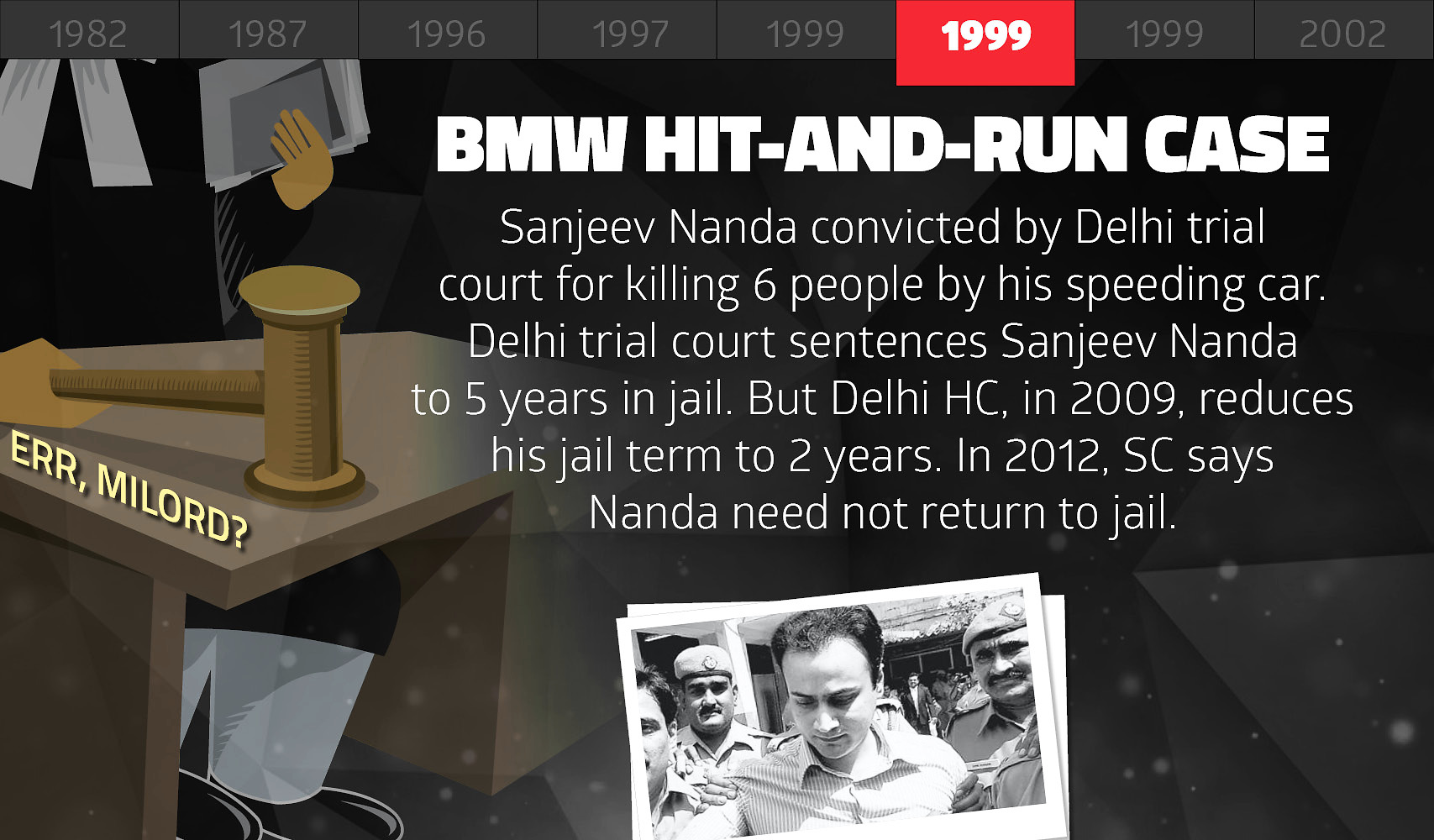

In the 1999 BMW hit-and-run case, Sanjeev Nanda, grandson of former Naval Chief S M Nanda was convicted by a Delhi trial court for killing six people with a speeding car. In 2008, the trial court sentenced him to five years in jail after holding him guilty of culpable homicide not amounting to murder. But the Delhi High Court, in 2009, reduced his jail term to two years after quashing the charge of culpable homicide not amounting to murder. According to the HC, Nanda's was a simple case of causing death by rash and negligent act. In 2012, the Supreme Court shot down the Delhi Police’s appeal to enhance Nanda’s sentence and said he need not return to jail.

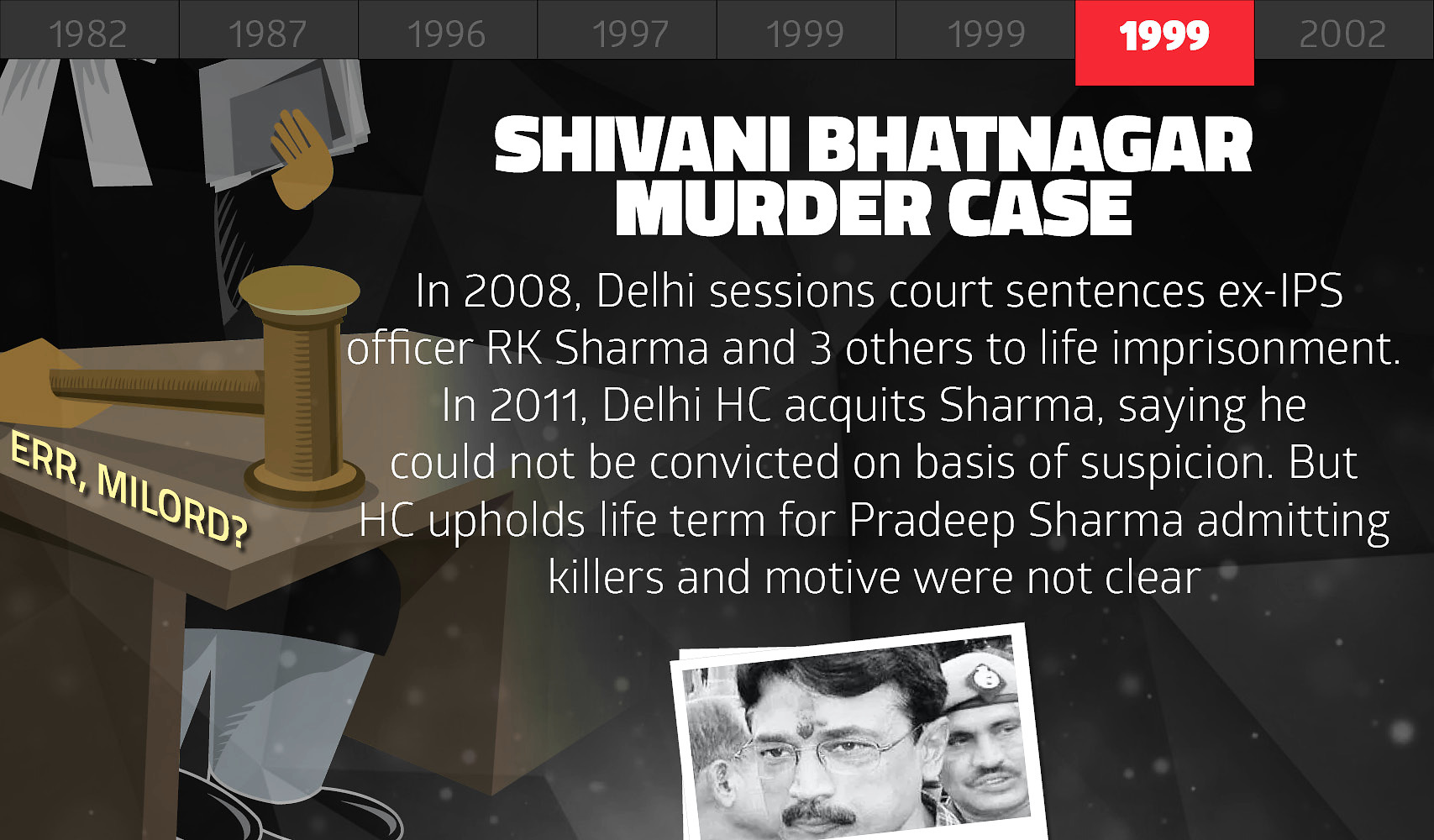

In the 1999 Shivani Bhatnagar murder case, former IPS officer RK Sharma was held guilty by a Delhi sessions judge of getting Bhatnagar, an Indian Express journalist, killed by hitmen. The trial court, in 2008, sentenced Sharma along with three others to life imprisonment under murder and conspiracy charges. However, in 2011, the Delhi HC acquitted Sharma, saying he could not be convicted only on the basis of suspicion. Interestingly, the HC did uphold the life term for one convict, Pradeep Sharma, even though admitting that it was not clear that who were behind the killing and what was the motive.

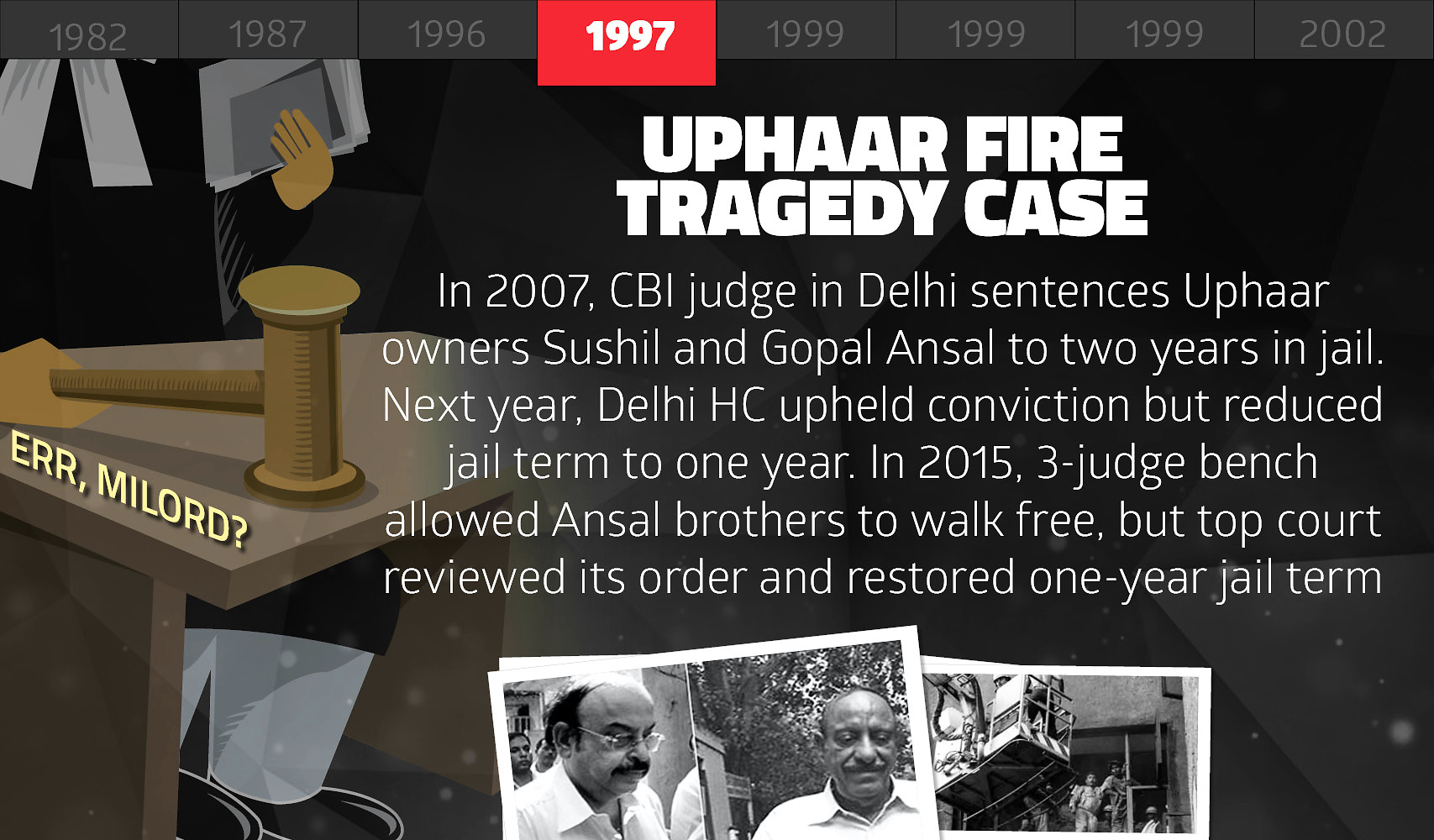

In the 1997 Uphaar fire tragedy case, 59 people died of asphyxia as the south Delhi cinema hall caught fire during the screening of a Hindi film. More than 100 people were injured in the subsequent stampede. In 2007, a CBI judge in Delhi sentenced real estate tycoons and Uphaar owners Sushil and Gopal Ansal to two years in jail for causing death due to rash and negligent acts. Next year, the Delhi HC upheld their conviction but reduced their jail terms from two years to one year. The case took an intriguing turn in 2015, when a three-judge bench allowed the Ansal brothers to walk free even without undergoing the one-year jail term. Amid an outrage over this order and a forceful petition by the victims’ association, the top court finally reviewed its order and restored the one-year jail term.

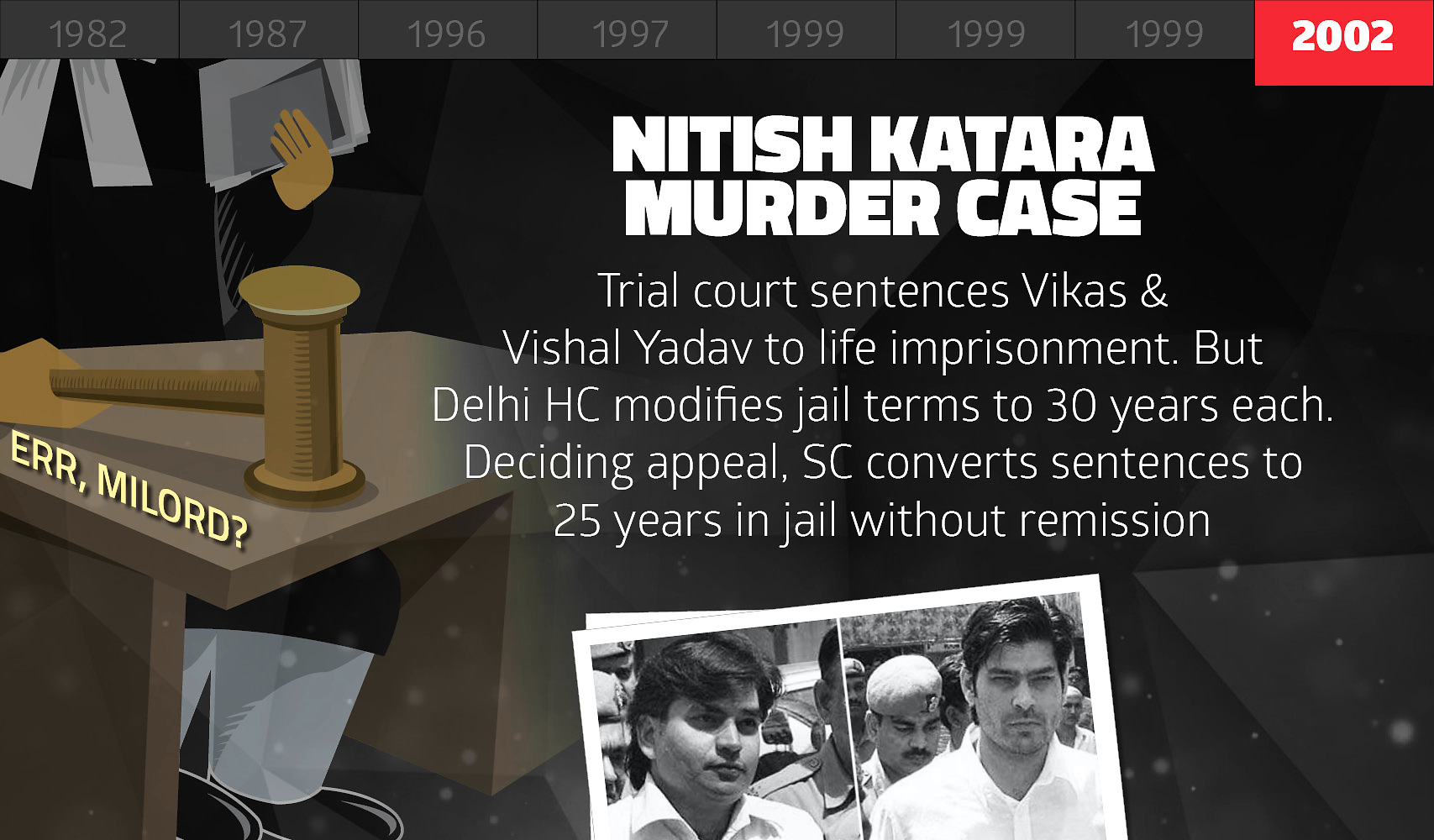

In the 2002 Nitish Katara murder case, the trial court held cousins Vikas and Vishal Yadav guilty of abducting and killing Nitish Katara over the latter’s affairs with their sister. While the trial court sentenced the duo to life imprisonment, the Delhi High Court modified their jail terms to 30 years each. Hearing an appeal, the apex court converted their sentence to 25 years in jail without remission.

In the 1987 ACP Tyagi custodial death case, a Delhi Sessions Judge had given death sentence to former Assistant Commissioner of Police RP Tyagi in connection with the custodial death of a Scheduled Caste man. When Tyagi appealed to the Delhi HC, not just the murder and conspiracy charges were nixed by the superior court, his death sentence was also reduced to eight years in jail.

In the 1982 Parcel bomb case, a Delhi court had handed out life term to Lieutenant Colonel (retired) S J Chaudhary for killing Delhi-based businessman Krishan Sikand with a parcel bomb. The Delhi High Court later acquitted Chaudhary for the want of evidence and curtains were drawn on the 34-year-long legal battle by the Supreme Court in December 2016, when it upheld the acquittal.

In the 1999 Jessica Lal murder case, a Delhi court in 2006 acquitted prime accused Manu Sharma due to lack of evidence. This caused a massive outrage in public and when the matter was up for appeal, the Delhi HC set aside the exoneration. It sentenced Manu to life term based on the same set of evidence and the top court also upheld the conviction in 2010.

In the 1996 Priyadarshini Mattoo murder case, accused Santosh Singh was acquitted by a CBI court in Delhi that slammed the agency for its shoddy probe. Relying upon the same evidence and giving them a different interpretation, the Delhi HC in 2006 overturned the trial court’s judgment and awarded death penalty to Santosh for raping and killing Priyadarshini. The Supreme Court later commuted his death sentence to life term after an appeal.

Therefore, there exists a long list of cases which were under constant media glare and the trial court judgments were quite often overturned or modified by the superior courts.

Criminal trials hinge essentially on evidence and procedure, which are examined, appreciated and interpreted by the courts during the trial. Facts and circumstances are the most important factors in the process of conducting a criminal trial.

A judge will have his own way of appreciating evidence and to attach credibility to it in accordance with his own understanding of the legal principles. He may borrow intellect from a catena of judgments delivered by the constitutional courts on a particular point, but eventually, the interpretation and the final conclusion have to be in the light of the facts before him. Every case will depend on its own facts and therefore, a certain degree of subjectivity in the interpretation is not just bound to occur, but is also a must to give a trial judge the necessary autonomy to decide cases and meet the ends of justice.

Even as trial courts rummage through evidence and try to attain utmost objectivity, there has been much recognition of the fact that high-profile cases and media trials are likely to influence the trial judges, who even otherwise work in a difficult environment.

Also, lack of infrastructure and amenities in trial courts across the country is nothing new. The pressure of the number of pending cases and an appraisal system that values the number of judgments delivered and the reputation of these judgments before the high courts add to the problem.

One adverse remark against a judicial officer by a high court bench may mean catastrophe against the former, who must tick every box before his or her status is upgraded. Adverse observations made by a high court can find their way into the annual confidential records of the judicial officer and are certain to affect his or her career.

Wary of every move, a judicial officer is apparently under an additional pressure when a trial is always in the headlines. Media trials, as has been acknowledged even by judges of the Supreme Court, including Justice Kurian Joseph, tend to “create a lot of pressure on the judges”.

In an event organized by lawyers in Kerala, Justice Joseph had recalled how a judge told him that "had he not given that punishment, people would have hung him". Similarly, a Delhi HC bench also noted that in cases being scrutinized by the media, there is subconscious pressure on the judges and “it does have an effect on the sentencing of the accused/convict".

Thus, the duty assigned to a trial court judge is an onerous one, made more arduous by an increasing and intense public focus on sensational cases and the media microscope, which are likely to remain there forever.

The Supreme Court has ardently acknowledged the complexities of a trial and the challenging task at the hands of trial court judges. It is in this context that the apex court has implored upon the high courts to remember that the primary purpose of pronouncing a verdict is to dispose of the matter in controversy pending before it and not to sit in judgment over the conduct of subordinate officers.

A series of Supreme Court verdicts have time and again underlined that “the human element in justicing” is an important element and that computer-like functioning cannot be expected of the courts, and therefore, “the premise that a Judge committed a mistake or an error beyond the limits of tolerance, is no ground to inflict condemnation on the Judge-Subordinate, unless there existed something else and for exceptional grounds.”

In Braj Kishore Thakur’s case (1997), the top court held that “no greater damage can be caused to the administration of justice and to the confidence of people in judicial institutions when Judges of higher Courts publicly express lack of faith in the subordinate judges.”

Several judgments emphasized that in order to maintain the independence of the judiciary, every judicial officer, however junior, should feel that he can fearlessly give expression to his own opinion in the judgment that he delivers.

“If our magistrates feel that they cannot frankly and fearlessly deal with matters that come before them and that the High Court is likely to interfere with their opinions, the independence of the judiciary might be seriously undermined…There is nothing more deleterious to the discharge of judicial functions than to create in the mind of a Judge that he should conform to a particular pattern which may, or may not be, to the liking of the appellate court,” the Supreme Court has held in multiple judgments.

If one tends to examine the necessity and propriety of the strictures used by the Allahabad HC against the trial court judgment in the Aarushi case, a 1962-judgment by the top court appears to explain why the condemnation could have been avoided.

In Ishwari Prasad case, the Supreme Court had underscored that the impression formed by the judge about the character of the evidence will ultimately determine the conclusion which he reaches.

“But it would be unsafe to overlook the fact that all judicial minds may not react in the same way to an evidence and it is not unusual that evidence which appears to be respectable and trustworthy to one judge may not appear to be respectable and trustworthy to another Judge. That explains why in some cases, courts of appeal reverse conclusions of facts recorded by the trial court on its appreciation of oral evidence,” said the court.

It further cautioned the superior courts saying, “The knowledge that another view is possible on the evidence adduced in a case, acts as a sobering factor and leads to the use of temperate language in recording judicial conclusions. Judicial approach in such cases would always be based on the consciousness that one may make a mistake and that is why the use of unduly strong words in expressing conclusions, or the adoption of unduly strong intemperate, or extravagant criticism against the contrary views which are often founded on a sense of infallibility should always be avoided.”

Given a strong possibility of the murder case coming in appeal before the Supreme Court, there is a strong likelihood we hear again about the "duty of restraint" and "humility of function".

Comments

0 comment