views

Developing Imagery

Brainstorm a subject for your poem. Finding a subject (or list of subjects) that you want to write about can be daunting. While it can be tempting to use some grand poetic theme, such as love, something small and specific is typically easier to work with. Go out in public and immerse yourself in your surroundings – no headphones or texting your friends. Get a notebook and a pen, sit somewhere, and observe the world around you. Jot down things you see that interest you or make you feel something. If you see something that evokes a strong emotion in you, you're more likely to be able to communicate that emotion through a poem.

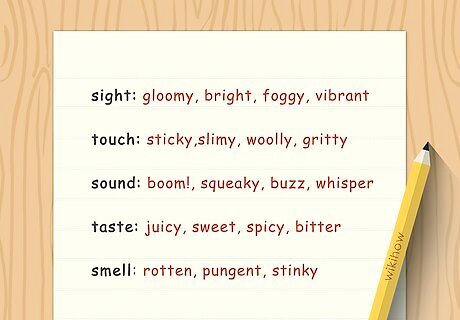

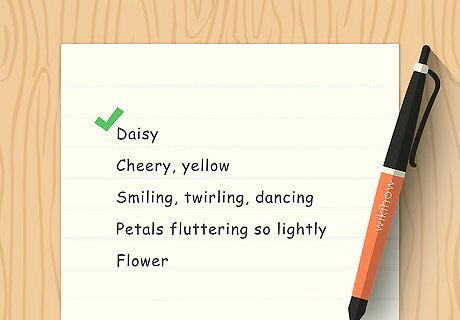

List words for all 5 senses. An imagery poem uses sensory description to evoke a particular image and feeling in the reader's mind. Don't associate the word "image" with visual images alone, however. Sounds, smells, and tastes can also evoke images. Not all 5 senses are going to be relevant for every subject, but it's a good idea to go ahead and brainstorm all 5 and see what you come up with. It may be that something you assumed would be irrelevant turns out to create a more compelling image. For example, you might not associate taste with a playground, but if you're writing about a child who falls face first onto the ground, you could evoke that image with the taste of a mouthful of dirt and grass. Don't be afraid to play around with the senses and mix your words up as well. Synesthesia is a neurological condition that enables some people to see sounds, or taste words. But even if you don't have the condition, you can still mash up sensory perceptions and to find unique ways of perceiving the world.

Tie description to action. Adjectives aren't the only words that describe things. Different nouns and verbs can also evoke a particular feeling, adding depth to your image. For example, verbs such as grasp or clutch have different connotations than hold, even though all of these words have similar literal meaning. If you aren't sure about the connotation of a word, look it up in a dictionary or thesaurus first. The image you create should be consistent, and a word that doesn't match the others can distract the reader and take them out of the poem.

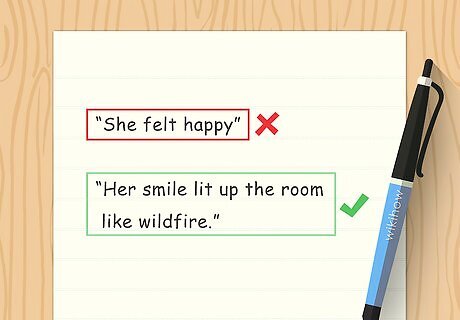

Avoid being literal. With an imagery poem, you want to conjure up an image or feeling in your reader's mind without telling them exactly what you're describing. Instead, show them the sensory details. For example, suppose you're writing a poem about walking to the grocery store. You could simply say "I walked to the grocery store." But for an imagery poem, instead of telling your reader what happened, you would show them everything absorbed by the senses on that walk to the store. In this way, the reader takes the same walk in their mind.

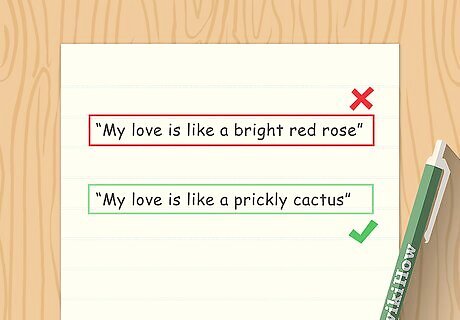

Read other poetry. The key to a good imagery poem is to use sensory descriptions that aren't cliched and commonplace. Readers won't connect to something they've already read before in the same way they connect to something new. But you can't know what's already been used before if you don't read the work of other poets. This doesn't mean you need to read every poem ever written (that would be impossible), or even that you need to read all the "great" or "classic" poems. Read poetry written about topics that interest you, because that's what you'll be writing about. Read actively, taking notes as you read. Think about what works and what doesn't. If a poet creates a strong image that resonates with you, break down the poem to figure out how the poet managed to do it.

Writing

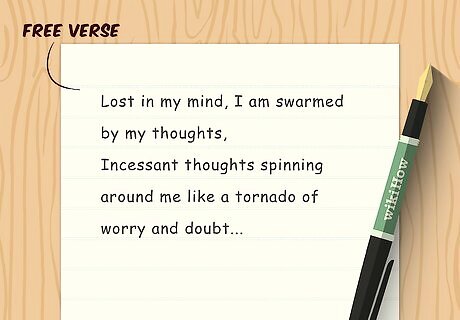

Start with a free write about your subject. Sit down with a blank page and let the words flow. Try to keep your writing as automatic as possible, without thinking about it or even looking at the page more than necessary to keep your writing relatively orderly. Free writing is a way to loosen yourself up mentally and start writing without worrying too much about the structure or form the poem will take. If you simply write, you'll find that the form that works best for the poem will reveal itself to you.

Fit the structure to the poem. Rather than setting up a structure first and trying to force your words into that form, look over your free write and try any form your writing suggests. At least when you're first starting, free verse typically will be the easiest structure to use, because you don't have to worry about rhyme and meter. Focus on meaning rather than a particular form. Rhyming can be particularly difficult to pull off without the words sounding forced to fit the rhyme scheme. If you can't get a particular form to work, feel free to abandon it and find something that will work better. If you're grouping your lines into stanzas, make sure there's a reason for doing so that relates to the meaning of your poem. While you want to think about how your lines look on the page, you don't want to choose a particular spacing solely for this reason.

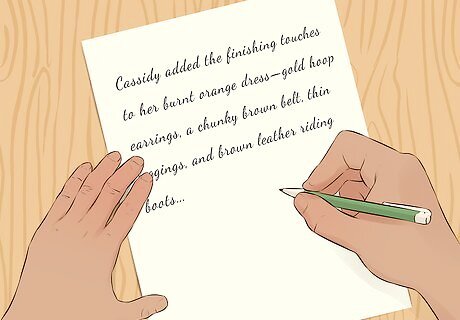

Use specific and concrete words. You can draw readers into your poem and create the image you want them to create in their minds by making your words as specific as possible. Abstract, generic words don't have much meaning on their own, and your reader will define them with reference to their own experiences and understanding rather than the image you're trying to communicate. For example, a word like "pain" has no real meaning apart from whatever understanding the reader brings to it. A mother of 3 may have an entirely different concept of pain than a teenaged boy, and that teenaged boy may have a different concept of pain than one of his peers who experienced a near-fatal car accident. In your initial drafts, you can use these words as placeholders. Ultimately, if you want to write a good imagery poem, you'll replace them with vivid sensory descriptions of the pain felt.

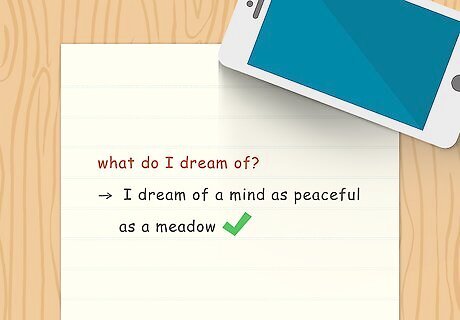

Ask questions to draw out meaning. In a poem, every word should be important to the ultimate image you are trying to convey. Go through your draft and ask yourself why each detail is necessary to the poem as a whole. If the reason for a particular detail isn't clear, you may need to add more to your poem, or you may simply want to throw it out and see how the poem works without it. If you've written a turn of phrase that you've fallen in love with, but it doesn't add anything to the meaning of the poem as a whole, you're better off without it. Save it for use in a different poem.

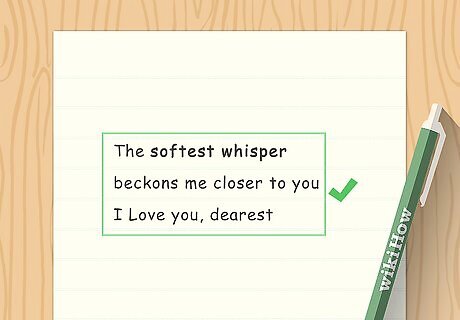

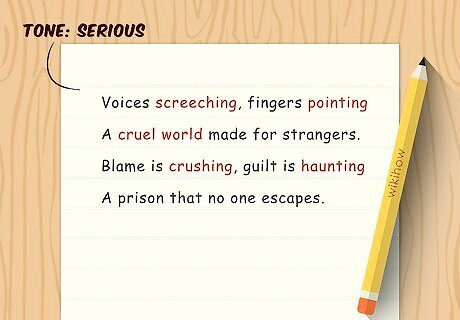

Choose words and phrases that evoke the right mood. Writing an imagery poem is not about taking a photograph with words. Rather, you want the sensory descriptions you use to be ones that make the reader feel the way you want them to feel. Words beginning or ending in hard sounds, such as brick or shut, can evoke more of a cold, closed-off sensation in the reader. In contrast, soft, gentle words such as rolling or whisper can calm and warm the reader. The repetition of hard or soft consonants can evoke a mood that carries through the entire poem. Repetition can also help create rhythm in your poem.

Revising

Take a break from your poem. After you've written a solid draft of your poem, let it sit for a few days – or even a few weeks – before you start the editing and revision process. Editing will be a waste of time unless you can look at your poem with a cool, objective eye. It may be that you don't have time to take a long enough break from your poem for whatever reason, such as a class deadline or an event. In that situation, there are things you can do to create some distance, such as going for a walk or doing another activity for awhile. Another way to look at a poem with fresh eyes is to simply write it again. If your draft is hand-written, type it on a computer. If you've already typed it, print up your draft, then open a new document and type it all over again.

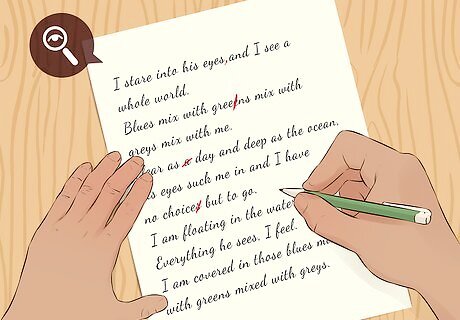

Correct glaring errors. When you come back to edit your poem, you may notice an error that should have been obvious before. This is why it's so important to have fresh eyes when you start editing and revising your poem. Reading your poem backwards can help you identify mistakes or typos that you might not have noticed just reading it through. Keep your proofreading separate from your substantive editing and revision. Get it out of the way first thing so you can focus on the meat of your poem.

Read your poem out loud. Reading aloud enables you to easily identify parts of your poem that may not be working. It also gives you a sense of the internal rhythm of your poem, and parts that may not flow as well as they should. Pay attention to where you naturally pause as you read, and make sure the punctuation and line breaks in the poem reflects your reading. Another way to check punctuation and line breaks through reading aloud is to exaggerate the length of the pause you make. This puts the pauses in focus so you can identify unnecessary commas or awkward line breaks.

Cut unnecessary words and phrases. An effective poem gets its message across in as few words as possible. Start with articles such as "a" and "the." Conjunctions (and, or) often aren't necessary in poetry either. Highlight adverbs and think about how you can use an active description instead. A specific verb may take care of the problem for you. For example, you might use "clutched" instead of "held tightly." Look for any word that could have more than one meaning depending on the person reading the poem. Work on making these words as specific and concrete as possible. For example, instead of "red" (which could be a number of different shades) you might use "ripe cherries."

Adjust the structure as necessary. As you revise your poem, you may find that a structure you once liked is no longer working. Even the smallest change you make to a poem can affect everything else. Take a step back occasionally as you're revising and look at the poem as a whole. Make sure the structure continues to serve the meaning of the poem, and not the other way around. If you find you're trying to force words into place, it may be that the structure you originally chose no longer fits. During the revision stage, you may also want to play around with different forms or ways of structuring your poem to see the difference. You may find that moving the lines and spacing around gives the poem a new depth you hadn't considered before.

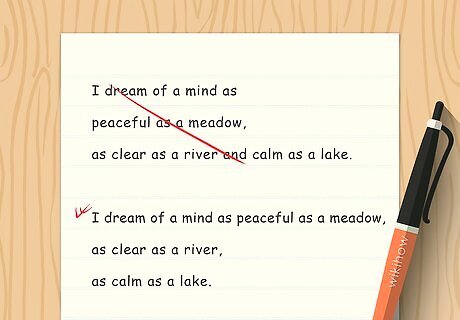

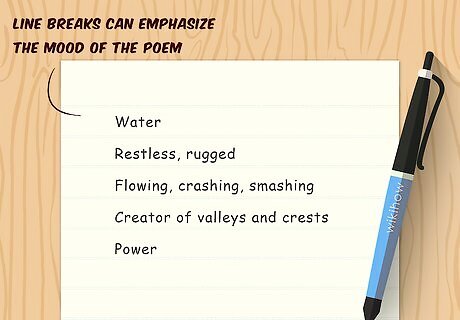

Experiment with line breaks. The length of your lines, and where they are broken, can emphasize particular sensory descriptions over others as well as help set the mood of your poem. How your poem looks on the page plays a role as well. If you're writing in free verse, you can try a number of different options and see which one works best. For example, you might do a revision in which you keep all the lines of the poem as close to the same length as possible. Then you might do another with varying long and short lines. Simply how a poem looks can enhance the mood or detract from it. Generally, readers may have difficulty if the lines are all over the page and there doesn't seem to be any reasoning behind the spacing you used.

Get other people to read your poem. Provided you're not too shy about your writing, other people can provide good constructive feedback that can help your poem be the best it can possibly be. The people you share your poem with don't have to be poetry experts (or even write poetry themselves), but they should be people you can count on to be honest. Most people who have no training in constructive criticism will just tell you whether they liked it or not. Knowing someone else liked your poem may feel good, but it doesn't help you improve your poetry. Ask questions about what worked and what didn't to draw out feedback you can use. If possible, it can also be helpful to ask someone else to read your poem aloud. Notice the places where they read it differently than how you did. If you like your read better, figure out a way to make what's on the page better reflect how you read it. For example, you may need to break a line differently, or change a comma to a semi-colon to indicate a longer pause.

Comments

0 comment