views

Developing a Strong Rebuttal

Know your argument. You need to have a solid grasp of the topic, your stance on the topic, the reasons that support that stance, and the evidence that you will use to support those reasons. It’s easiest to know your argument if you have a written case, but in an impromptu setting, you can keep up with the argument you or your team is presenting by taking good notes. If you have a written case, study both the case and outline before the debate. Underline important points, and know where your evidence is sourced. If you are going to be developing your arguments during the debate, review the evidence that you could offer, as well as possible arguments that can be made under the established topic for the debate. This way you will be able to quickly choose an argument or piece of support when you are in the middle of the debate.

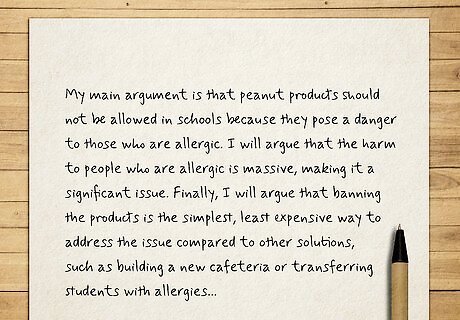

Write out your 3 or 4 main arguments. Since your opponent will be attacking your arguments, you can anticipate what they will say if you take a long, hard look at your main arguments. If you have a written case, this will be easy. Simply highlight and outline your main points. If you don’t have a written case, choose the arguments that are the most likely to be brought up under the established topic. For example, you could write the following: "My main argument is that peanut products should not be allowed in schools because they pose a danger to those who are allergic. I will argue that the harm to people who are allergic is massive, making it a significant issue. Finally, I will argue that banning the products is the simplest, least expensive way to address the issue compared to other solutions, such as building a new cafeteria or transferring students with allergies."

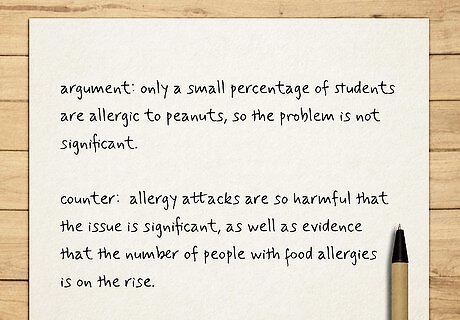

Identify the possible arguments against your argument. This activity should be done before the actual debate. Knowing what your opponent may present against you can allow you to develop your rebuttals faster during the actual debate. Look at the 3 or 4 main arguments that you plan to present, and think about how you would attack them. Develop a plan to counter these attacks. For added insight, ask another debater how they would counter your arguments. Write out possible defenses to these potential arguments. This exercise will give you ideas to come back to later while you’re in the debate. For example, you could anticipate that your opponent may argue that only a small percentage of students are allergic to peanuts, so the problem is not significant. In response, you could plan to offer evidence showing that allergy attacks are so harmful that the issue is significant, as well as evidence that the number of people with food allergies is on the rise.

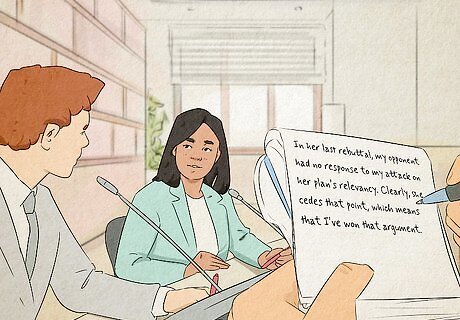

Keep track of the arguments made by both you and your opponent. Take good notes during the debate so that you remember to address new arguments that are brought up and don’t accidentally forget about arguments that you’ve already made. You will also be able to see when your opponent fails to address one of your arguments so that you can point out to the judge that you have won that point. Say, "In her last rebuttal, my opponent had no response to my attack on her plan's relevancy. Clearly, she cedes that point, which means that I've won that argument."

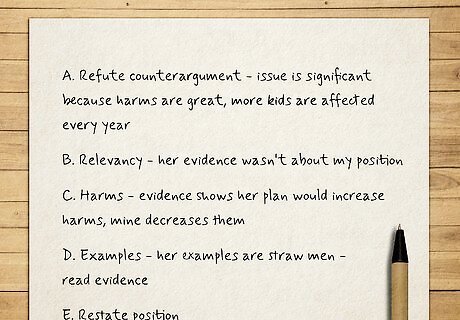

Make an outline of your arguments to refer to as you rebut. Don’t write out a whole speech because this will waste your preparation time and will likely cause you to read from the paper instead of making eye contact with the judge. Instead, put your arguments into an outline that you can refer to in order to make sure all of your points are addressed in your rebuttal. Your outline might look like this: A. Refute counterargument - issue is significant because harms are great, more kids are affected every year B. Relevancy - her evidence wasn't about my position C. Harms - evidence shows her plan would increase harms, mine decreases them D. Examples - her examples are straw men - read evidence E. Restate position

Delivering a Solid Rebuttal

Attack new arguments first. Most debates have more than one rebuttal, and you should always start with new arguments. They will be fresh on the judge’s mind, so you need to address them as soon as possible. Make sure to save room in your time allowance to briefly review your other arguments. If you believe you have already won an argument or that the other team dropped one, you can briefly summarize those points at the end of the speech, reminding the judge that they go to you.

Remind the judge of your opponent’s argument. Provide a one-sentence summary of what your opponent has said. Take it one argument at a time, starting with the one that is either easiest to defeat or the most crucial to your case. Say, “My opponent wants to allow one of the most common allergens into our nation’s schools, regardless of how many students are at risk.”

Restate your position. Remind the judge what your argument is, positioning it as the clear better choice over your opponent. Choose your words carefully so that your argument appears to be the most reasonable choice. Say, “A safe educational environment is necessary for all students. We stopped sending students to schools that have asbestos; now we need to stop sending them to schools that have peanuts.”

Break down your rebuttal into two choices for the judge. Present the breakdown with your argument framed as the best choice. Make the case seem simple to the judge, but say it in a way that makes it seem like picking the other side is preposterous. For example, “The choice is simple: We can protect students from life-threatening allergy attacks, or we can allow a few students to eat peanut butter for lunch.” This argument makes it seem like critical health emergencies are being pitted against something as trivial as a sandwich.

Explain the reasons why your argument is best. Link your argument back to the topic, and provide evidence to back it up. Tell the judge why this evidence proves that your argument is superior to your opponent’s argument. This should take several sentences and possibly several minutes, depending on how many arguments you plan to address in your rebuttal. Never list off your reasons without offering an explanation. Your rebuttal depends on your explanation of the argument. Say, "My plan to remove peanut products from schools fulfills the resolution to provide a safe learning environment for kids by removing a known, common hazard. The evidence shows that the threat to allergic individuals is great and that every day the number of allergic students walking the hallways increases. The easiest, least expensive way to protect students is to ban peanut products. Please vote for safe schools by voting for me."

Show the judge why this argument is a voting issue, which you won. You and your opponent may both win arguments within the debate, but the judge still has to pick a winner. Voting issues are the arguments that could make or break a case, so showing that your argument is a voting issue could make the judge choose your side. For example, relevancy is often a good voting issue because if an argument is not relevant, then it is ineffective. If you show the judge that your opponent has no relevancy on the topic, then that could be a voting issue that goes your way. Say, "My opponent argued that we should ban sugary foods instead of peanut butter, but that is not relevant to my case. None of the evidence she provided about the dangers of sugary food should be considered."

Give a concluding statement urging the judge to choose your argument. Briefly summarize your arguments and the voting issues, then urge the judge to vote for you. Say, “The evidence I’ve provided proves that my opponent’s argument lacks relevancy and fails to address the topic. Additionally, my opponent has falsely assumed that peanuts must be ingested to be harmful, which is factually untrue. For these reasons, you should vote for my case.”

Avoid dropping an argument. If you don’t address an argument, it could go to the other team. Even if you are losing an argument, it’s best to offer a short concession in your rebuttal before moving on to your stronger arguments. If your opponent points out that you dropped an argument, it will look worse than if you concede it yourself. You should also watch for arguments that your opponent has dropped. Make sure to point this out to the judge and tell them that you have clearly won that point.

Scoring Off Your Opponent's Points

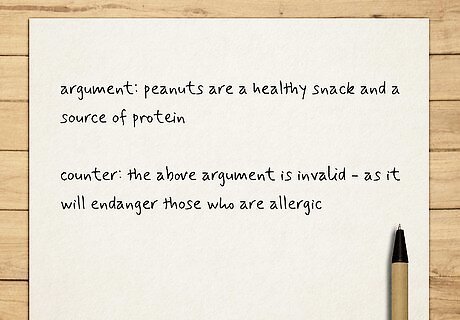

Show that your opponent’s arguments or evidence are not relevant. Sometimes your opponent will offer a related argument or piece of evidence that doesn’t quite match up with what their stance should be. This can be tricky to catch since their argument may seem on topic; however, they have to prove their stance on the issue at hand, not a related point. For example, let’s say your argument is that peanuts should not be allowed in schools to protect students who are allergic. If your opponent argues that peanuts are a healthy snack and a source of protein, their argument would not be relevant because they had to show that peanuts could be allowed on campus without endangering those who are allergic.

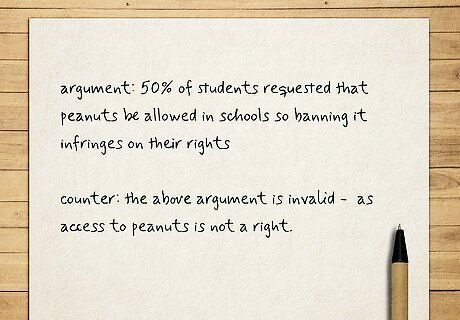

Break the logical links in your opponent’s argument. Look for a weak link in your opponent’s logical jumps between their stance, their points, or their evidence. Point out the reasons why this logical leap does not make sense. For example, if your opponent argues that 50% of students requested that peanuts be allowed in schools so banning it infringes on their rights, you could argue that there is no logic there because access to peanuts is not a right.

Argue that your opponent has made a false assumption. With this strategy, you can acknowledge that your opponent’s argument sounds good but that it’s flawed because they are assuming the wrong conclusion about their points. For example, if your opponent argued that people who are allergic to peanuts would be safe as long as peanuts were always labeled, you could point out that your opponent was assuming that people only experience a peanut allergy if they eat them. You could then point out that some people are triggered by peanut protein on other people or surfaces. Similarly, you could concede part of the argument but then counter that something else is more important. For example, peanut butter is an inexpensive protein option that is easy for students to eat on the go, but the lives of students who are allergic are more important than convenience.

Undermine the impact of the opponent’s argument. With this strategy, you can acknowledge that their argument addresses the issue but doesn’t fix anything. Because their argument fails to make a difference on the topic, your argument should prevail. For example, your opponent could offer a counter-plan that students be able to eat peanuts at an outdoor table. However, you could then point out that the peanut residue could still harm students who are allergic, leaving the problem unsolved.

Attack the base argument if more than one is offered. Sometimes your opponent will offer two arguments that work together to make a stronger argument. If one or more of their arguments depend on one base argument being true, then you can address all of them at once. For example, if your opponent argues that banning peanuts infringes on students' rights thereby causing them to fear authority, you could defeat the whole argument by showing that students' rights are not being violated by the peanut policy.

Point out contradictions. Sometimes there are two good arguments against you that contradict themselves or the point of the topic. If your opponent makes the mistake of using these contradictory arguments, use that against them in your rebuttal. For example, your opponent may argue that the number of students who bring peanuts to school is low, so there is little risk in allowing them. If they also argue that peanuts should be allowed because a majority of students want them, then this could be pointed out as a contradiction.

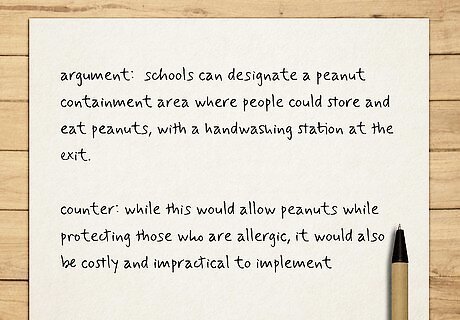

Show why their argument isn’t practical. Your opponent may have an argument that could solve the issue but isn’t really feasible because of money, time, lack or resources, public opinion, or any other logical reason you can think of. If this is the case, you can use this lack of practicality in your rebuttal to undermine their position. For example, your opponent could suggest that schools designate a peanut containment area where people could store and eat peanuts, with a handwashing station at the exit. While this would allow peanuts while protecting those who are allergic, it would also be costly and impractical to implement.

Address their examples last. If you have time at the end of your rebuttal, you can address the examples they gave to back up their argument, such as anecdotes, analogies, or historical facts. Pick out their poorest examples and explain to the judge why they are weak or why they don’t support the opponent’s argument. For example, you could point out that anecdotes can be made up, or why an analogy doesn’t work. Start with the weakest example and continue until you have just enough time to sum up your rebuttal and offer your concluding statement.

Comments

0 comment