views

Remembering Facts

Put the information in a rhyme. Using rhyming and even melodies can help you remember facts. By incorporating rhythm or the tune of a simple song into your memorization you can also help your understanding of how key events, people, dates, etc. fit together. The old saying “In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue,” is a great example of how rhyming can help commit information to your long-term memory.

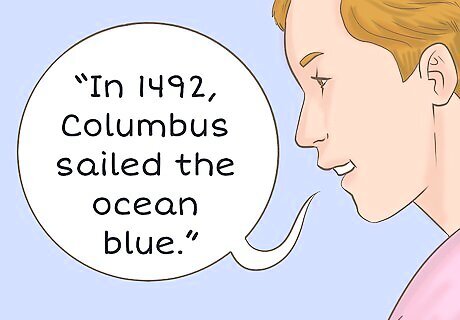

Make up a mnemonic device. By taking the first letter of a series of related key words and using to invent a silly and memorable phrase, you can recall things in a specific order. This can be especially useful when trying to remember things in the order in which they happened. For example, "Gill Underestimated Cliff’s Strength” is a mnemonic for remembering who the main Allied powers were during World War II: Great Britain, the United States, China and the Soviet Union.

Use your other senses to trigger your memory. If you study while smelling a certain notable scent (like rosemary, for example), and then use that scent later when you need to recall the material, studies suggest you’ll have a greater recall ability. Similarly, studying while listening to calm music can help you recall the material again later.

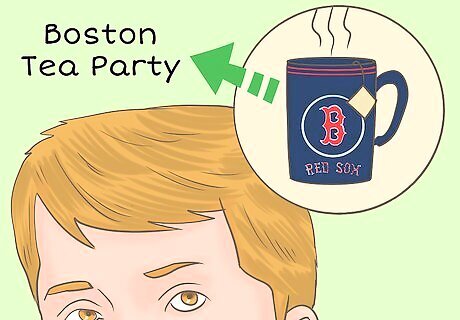

Use visualization. When trying to commit a fact to memory, try to associate it with an image in your head. It may even help to draw the image out if you are a really visual learner. The image doesn’t necessarily have to be direct in its meaning. For example, if trying to learn facts about the Boston Tea Party, you might picture a Red Sox mug filled with hot tea.

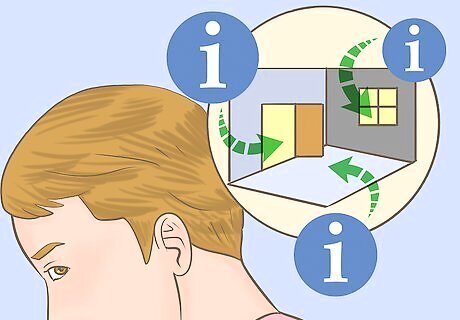

Use the loci method. Associate different historical facts, events or phrases with a different part of your home in the order that you would normally walk through it. For example, to remember the outbreak of World War I associate the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Sophie the Duchess of Hohenberg on June 28, 1914 with your front door. Visualize your entryway to your house in relationship to the fact that Austria-Hungary blamed Serbia for the killings and declared war on July 28, 1914. An ancient memorization technique, the loci method has you construct a "memory palace" using a building you know well (like your home). If trying to remember a chain of historical events, you might associate the first event with the front door to your home, the second with the entryway, the third with your living room, etc.

Using Flashcards

Make a list with the information you need. Make one big list of all the key terms, people and dates that you need to know from your textbook, class notes and any handouts that you may have on the subject. If you are studying American history in the 1930s, for example, you might have a list that includes key terms like “the Dust Bowl” “the Great Depression” “Franklin D. Roosevelt,” and “the New Deal,” among others. Write your list by hand. Studies show that memorization works best when you write things out by hand vs. on the computer.

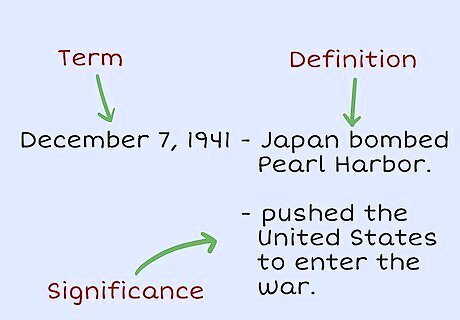

Define each term and its significance. For each item on your list, you should write two or three sentences that describe what it is and why it is important. If it is a specific date or year, you will want to describe what happened on that date followed by why it is historically significant. For example, December 7, 1941 is the date that Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. Its significance is that this event pushed the United States to enter the war.

Transfer your list into hand-written flashcards. Take each entry from your list and turn it into a flashcard. Write the key term, name or date on one side, and its definition and significance on the other. Use red ink on a white background, as this has been shown to help with memorization. Index cards are great for making flashcards. It can be useful to cross-list key terms in your definitions so that you can remember how certain people, places, events or dates are related to one another.

Test yourself. Begin testing your memory of each term and its definition and significance, checking your answer against the back of the card. Say your answers out loud. When you are able to recite the correct answer, move the card to a separate pile so that you can focus on the ones you do not know. Continue going through the cards in the days and hours before you have a test or a paper due. This way you are more likely to commit the information to your long-term memory.

Making a Timeline

Make a list of important dates. Pull key dates from your reading materials, class notes and any class handouts you may have. Assemble this information in list-form, making sure you keep your dates in chronological order. For example, to remember the timeline of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, highlight specific dates and key events spanning from May 7, 1954 when Vietnamese forces clashed with the French at Dien Bien Phu through March 1973 when the last American soldiers left South Vietnam, ending a war without a clear resolution. Wars, political upheavals, and scientific or medical discoveries particularly lend themselves to timelines because the timeframe in which specific events happen are often face-paced, factually dense and build sequentially off of one another.

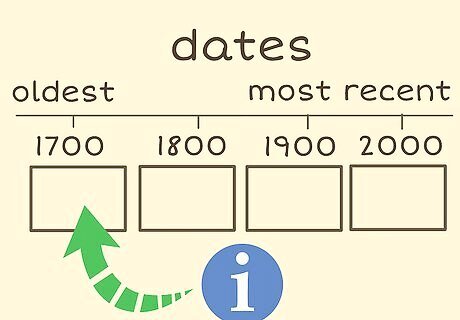

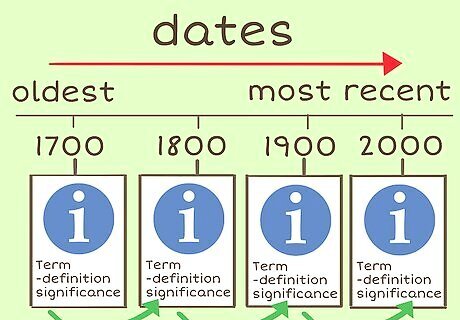

Assemble your timeline. Draw a straight line from one end of your page to the other. Then, begin filling in your dates in order from the oldest to the most recent. Draw a box next to each date and begin filling it in with the key information you need to remember. Make sure you include information about important people, events and places. Leave yourself plenty of space to fill in all the information you need.

Move forward in time. Continue filling in your dates in your timeline along with descriptions of what happened and why it is important. Make note of connections between events, people and places as you go by drawing arrows. Use color-coding and highlighting to make the timeline visually memorable. This can also help you to quickly identify important names, themes or other key terms that appear in your timeline more than once.

Spread out across multiple sheets of paper. Depending on how much information you have to memorize, you may need to make a timeline that extends across multiple sheets of paper. Simply add additional sheets as necessary. Your timeline can be one long sheet or you can keep it in a notebook. If you do have a multi-page timeline, make sure to number your pages so you can easily keep them in order.

Test yourself. Once you have studied your timeline, put it away and try to recreate it from memory. This will tell you what you really know. If you don't get everything right the first time, go back to review the parts that you missed. Once you can recreate everything from scratch, you will know that you have your history information memorized.

Working With a Study Group

Compare notes. Working with a partner or a small group, review your notes together. Make sure you have the same information. If there are discrepancies in your notes, refer to your textbook to see if you can resolve the issue. If this doesn’t work, don’t hesitate to ask your instructor for guidance. Just going through your notes with someone else can be a great way to review the material and to clear up any confusion or questions you may have.

Compile a study guide together. Meet with your group and divide up the study material. Task each person with making a list of key terms, dates, names, events, etc. and create one big list. Use the study guide to help direct your discussion by working down the list. Take turns providing definitions and share your thoughts on the historical significance of each term. For best results, each person should maintain their own copy of the study guide. Fill it in with notes from your conversation as you go down your list.

Quiz each other. Using flashcards, study guides or key term lists that you have put together, take turns quizzing one another. If someone gives an incorrect answer then discuss what the correct answer should be. Provide positive encouragement and support to one another.

Building Basic Study Skills

Review before a new lesson. Before attending a history lesson, review the materials you already have. These may include a syllabus, which will provide you with information on the day’s topic, notes from the previous lesson, and any reading assignments. Doing this work ahead of time will prepare you to focus on the new lecture material. Even if you have already done the reading assignment, it can help to review your notes on it right before class so that it is fresh in your mind. Come prepared with questions based on your review. If the lecture does not answer these for you, make sure you follow up with your instructor to get clarification.

Take hand-written, legible notes. Whether you are reading a text or listening to a lecture, you should write notes by hand. Write down main points as well as any names, dates and key events as they come up. Make sure you define them and note their importance. If you find that you are missing something, don’t get hung up on every little detail. Move on and note where you need to go back to fill in the additional information later. Write legibly in pencil or with blue and black ink. Record lectures to return to later if this is an option.

Break up your assigned reading. This is a method sometimes referred to as “chunking” because you basically break a text into smaller chunks that are easier to tackle than the text as a whole. Focus on the introduction and conclusion portions of the reading assignment first. These will help you learn what the main point or argument of the text is and will often summarize all the supporting points as well. Once you’ve identified the main argument and have a sense of what the smaller, supporting points will be, you can go through each paragraph to circle key names, dates, places, etc. Summarize the main point of each supporting paragraph in a few words and link these summaries to the overall point of the text.

Comments

0 comment