views

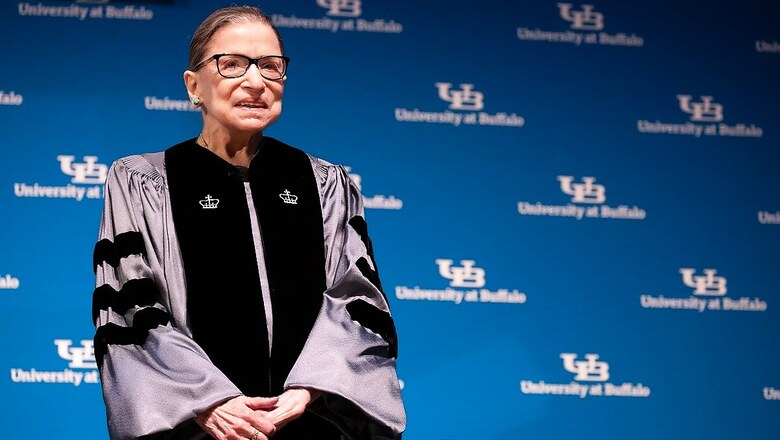

This February, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg reached the halfway mark of an unprecedented Supreme Court term, staring down what would be a momentous spring and what turned out to be the final months of her life.

Behind closed doors, the justices had already cast preliminary votes on disputes concerning immigration, LGBTQ rights and the Second Amendment and they had voted to add even more blockbuster cases to an already bursting docket on issues related to abortion, Obamacare and President Donald Trump’s tax returns.

Unbeknownst to the public, however, Ginsburg was battling another front. On the cusp of her 87th birthday, routine health scans in February revealed a recurrence of cancer with new lesions on her liver.

Departing from her usual practice of transparency on medical issues, Ginsburg, one of the most important women in the United States, decided to withhold the news from the public while her doctors settled on a treatment plan. She only disclosed the diagnosis some five months later, after the term was over.

Ginsburg made a choice. Instead of turning the public’s attention to her precarious health, she focused on the battle for her legacy. At key moments as her health challenges intersected with the court’s work, she dove in to fight for issues that have defined her career in areas such as abortion, voting rights, the death penalty and women’s preventive health.

Liberals were surprised and relieved to find themselves on the winning side of some critical cases that conventional wisdom predicted would be losses. The wins came as Chief Justice John Roberts sided with the left side of the bench.

But arguably, Ginsburg’s experience and seniority helped shape the reasoning from the bench and behind closed doors in a way that a younger, less experienced justice may not have.

At the same time, even some of biggest “Notorious R.B.G.” fans were frustrated when she did not retire during the previous Democratic administration.

“There were those who were disappointed she didn’t step down so that President Obama could fill her seat with a progressive jurist likely to serve for several more decades,” Elizabeth Wydra, president of the liberal Constitutional Accountability Center, said earlier this summer. “But Ginsburg is a fighter, and knows she can do her job on the court as no one else can at this moment.”

The diagnosis represented Ginsburg’s fifth bout of cancer, and as CNN’s Joan Biskupic reported, some, but not all of the justices were aware of the diagnoses last term.

Since 1999, she has battled the disease in the colon, lung, pancreas and the liver. Last August, just before the term began, she announced, for example, that she had completed a three-week course of radiation therapy to treat pancreatic cancer. Although she did cancel her annual summer visit to Santa Fe, she embarked on a speaking tour of sorts.

At one event sponsored by the Library of Congress in August 2019, she revealed that during her bouts with cancer she has often turned to work to distract from her health. “I love my job,” Ginsburg said. “It’s kept me going through four cancer bouts.”

“Instead of concentrating on my aches and pains, I just know that I have to read this set of briefs, go over the draft opinion,” she said.

Abortion case arguments

On the bench, after her cancer diagnosis, Ginsburg was her usual self.

For more than an hour during oral arguments on March 4, Ginsburg attacked a Louisiana abortion law that required doctors to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital. Lawyers for the state and the Trump administration urged the justices to allow the law saying it was necessary to protect public safety. Doctors and clinics argued that it would close all the clinics in the state except for one.

Ginsburg repeatedly pressed her perspective, dissecting each point brought up by supporters of the law. She noted that most abortions “don’t have any complications” and she said that if a complication were to occur it would happen once the woman returned home, perhaps nowhere near the clinic. She all but said that the law was medically unnecessary.

There was a reason she was zeroing in on that point. Just four years prior she had voted to strike down an identical law out of Texas. Back then Justice Anthony Kennedy was still on the bench and he sided with the liberals in a 5-3 decision to deliver a victory for supporters of abortion rights.

Like many, Ginsburg probably wondered if Roberts would be uncomfortable with the court radically changing its position just because the court’s composition had changed.

Ultimately, Roberts cast his vote with the liberals to strike down the law. He based his decision on how the court had ruled in 2016 in the Texas case.

“The Louisiana law imposes a burden on access to abortion just as severe as that imposed by the Texas law, for the same reasons,” Roberts said. Ginsburg’s side had pulled off an unexpected victory.

Voting rights and Covid-19

By April 6, the Supreme Court was faced with an emergency petition concerning voting rights in Wisconsin as the pandemic raced across the country. At issue was a lower court order that extended the deadline for absentee ballots to allow them to be postmarked after elections on April 7.

The court split bitterly 5-4 on the issue. In an unsigned order, the majority held in part that when the lower court extended the date by which ballots could be cast, it altered election rules too close to the election.

Ginsburg unleashed her fury in a dissent joined by the other liberals on the court, echoing a voting rights dissent she penned in 2013. In that 5-4 case, Shelby County v. Holder, the court gutted a key provision of the Voting Rights Act. Ginsburg furiously wrote in dissent that doing away with that section of the law was “like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

This time, she noted that Covid-19 had become a public health crisis and gathering at polling places posed “dire health risks.”

She said that she didn’t doubt the “good faith” of her colleagues, but that the court’s order would result in “massive disenfranchisement.”

“The Court’s suggestion that the current situation is not ‘substantially different’ from ‘an ordinary election’ boggles the mind,” she said.

Obamacare contraceptive mandate

Much had changed by May. Covid-19 had closed the courthouse doors to the public and the court was hearing unprecedented arguments over the telephone — broadcast live to the public for the first time ever.

On May 4 Ginsburg participated in oral arguments in a patent case and then traveled to a local hospital for outpatient tests that confirmed she was suffering from a gall bladder infection. The next day she participated in arguments again, but by that afternoon she was admitted to a Baltimore hospital to undergo treatment for what the court called a “benign gallbladder condition.” There was no mention of cancer.

But the hospital visit did not stop her from participating in oral arguments the next day from her hospital bed.

The court was hearing one of most important cases of the term: Trump’s attempt to broaden exemptions to Obamacare’s controversial contraceptive mandate that requires employer provided health insurance plans to cover birth control as a preventive service. Critics said Trump was attempting to weaken the mandate by offering exemptions to more people who had religious and moral objections.

To be sure, Ginsburg’s voice from the hospital room sounded weak. But she pressed hard on the issue. “This leaves the women to hunt for other government programs that might cover them,” she told Solicitor General Noel Francisco. “You have just tossed entirely to the wind what Congress thought was essential, that is that women be provided these services with no hassles, not cost to them,” Ginsburg added.

When the court ultimately ruled in favor of Trump, Ginsburg, joined by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, dissented.

“Today, for the first time, the Court casts totally aside countervailing rights and interests in its zeal to secure religious rights to the nth degree,” she wrote. She noted that by the government’s own numbers “between 70,500 and 126,400 women would immediately lose access to no-cost contraceptive services.”

An endless term

Even after the court’s 2019-20 term wrapped up, the justices were still battling over emergency petitions related to the federal government’s decision to reinstate the death penalty after 17 years.

At 2:10 a.m. on July 14, the court issued a 5-4 order that cleared the way for the execution of federal inmate Daniel Lewis Lee. Ginsburg voted in dissent. Like Breyer, Ginsburg believes the court should take a big step and revisit the constitutionality of the death penalty which she thinks is applied arbitrarily.

Hours later, the court’s public information officer released a statement saying that Ginsburg had been admitted to the hospital in Baltimore for treatment of a “possible infection.” It hadn’t stopped her from voting in the case.

By the time the court gavelled out in July, Ginsburg finally told the public that she was on a new bi-weekly chemotherapy regime to keep her cancer at bay. In her statement, she put to paper what she has said at various speaking engagements: she would do the job as long as she could do it full steam.

“I remain fully able to do that,” she said.

Comments

0 comment