views

Renowned violinist Yehudi Menuhin’s first visit to India was in 1952, when he was invited by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Thus began Menuhin’s long love affair with India. Nehru’s invitation had stemmed from his desire to invite leading musicians from across the world to expose our people to the best in art and artistes.

During his first visit, Yehudi Menuhin attended a private concert in which (Ali Akbar) Khansaheb and Panditji (Ravi Shankar) played a jugalbandi with Chatur Lalji on the tablā. Yehudi Menuhin was so impressed by the two maestros that he first took Khansaheb and then Panditji to the USA.

In his autobiography Unfinished Journey, Menuhin acknowledged, ‘Indian music took me by surprise. I knew neither its nature nor its richness, but here, if anywhere, I found vindication of my conviction that India was the original source. The two scales of the West, major and minor, with the harmonic minor as variant, the half-dozen ancient Greek modes, were here submerged under modes and scales of inexhaustible variety.’

Khansaheb gave North America its first major recital of Hindustani music at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. He featured on Alistair Cooke’s television programme Omnibus, and recorded the world’s first microgroove LP devoted to a musician from the subcontinent—Music of India: Morning and Evening Ragas (1955). Later that year, he gave a recital at London’s St Pancras Town Hall, again with Menuhin as the master of ceremonies, who introduced Ali Akbar Khansaheb as a maestro of the sarod. He called him ‘an absolute genius … perhaps the greatest musician in the world’.

Menuhin made several more visits to India. Once, when he was a guest of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, as a matter of courtesy, Indiraji asked Menuhin if she could extend any help to him while he was in India. Menuhin told the prime minister that he would like a favour from her, but doubted whether she could fulfil it. Knowing Indira Gandhi’s temperament, it became a prestige issue. She asked Menuhin to spell it out, and he said he wanted to listen to Annapurna Devi’s surbahār. It was not as easy a proposition as it seemed.

In Guru Ma’s words, ‘One day, the doorbell rang. I wasn’t expecting any disciple so I didn’t answer. However, the person kept ringing and shouting out, saying he had come with a message from the Prime Minister’s Office. At first I thought it was a prank. However, when I looked through the peephole, I saw a sepoy-like man wearing an unusual uniform. I gathered my courage and opened the door. He gave me an envelope, which he said contained a message from Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. I requested him to read it out to me. The message conveyed that the state guest, Mr Yehudi Menuhin, wished to listen to my surbahār.’

‘The messenger didn’t leave. He said he was waiting for my reply. He wrote down my reply, “Please convey this to Indiraji, that I am honoured that she hasn’t forgotten me after so many years. However, I have taken a vow not to play in front of anyone but to perform my sādhanā in front of the photo of my father-guru and Shārdā Ma.” Within a few hours after the messenger departed, Panditji messaged me stating that the prime minister had pressured him, stating marital discord should not be allowed to dishonor the request of a respected state guest, who also happened to be the world’s top musician.’

‘I chose to put the nation before self. I gave him conditional permission. I decided to make an exception and allow him to listen to me when I did my daily sādhanā, which is from about 2.30 a.m. to 4.30 a.m. I agreed to allow him to overhear from outside the door of my bedroom, where I did my sādhanā.’

George Harrison of the Beatles was also in Bombay then. He was with Panditji, and when he came to know about this, he decided to join Yehudi Menuhin. Harrison met Menuhin at the Taj Hotel lobby at about 1 a.m. As they were leaving, Menuhin got a wire message from his family that his father, Moshe Menuhin, had just been hospitalized after a heart attack.

Menuhin therefore rushed to the airport to catch the first available flight to New York. However, George Harrison came and heard Guru Ma’s sādhanā.

We asked Ma, ‘Yehudi Menuhin was very close to both Ali Akbar Khansaheb and Panditji. What was the need to drag Prime Minister Indira Gandhi into this?’

‘That was because both Bhaiyā and Panditji had expressed their inability to oblige him,’ Ma said. ‘Panditji knew that during our Delhi days, I had become quite friendly with Indira Gandhi, so they used Indiraji to pressure me.’

We were shocked to learn this, ‘You mean to say you personally knew Indira Gandhi?’ we asked Ma. ‘How did this happen?’ Ma explained, ‘From February 1949 until 1956, Panditji was working as the music director for AIR in New Delhi. Our accommodation was in a guest house adjoining the main bungalow of Bharatramji, the owner of DCM, who was a connoisseur of music. His wife first studied the sitār with Baba, and then from Panditji. His son Vinay learnt vocal music from me.’

‘Bharatramji used to arrange many baithaks at his house, and so did Karan Singhji, the son of Maharaja Hari Singh, the king of Kashmir at the time of Independence. Many Indian and some foreign dignitaries attended these

baithaks. Indiraji attended a few of them and we became quite friendly. At that time, she was assisting her father, Jawaharlal Nehru, the prime minister. I knew less about politics than she knew about music but, despite us having very little in common, we got along well and ended up meeting a few times.’

‘In 1968, Yehudi Menuhin came to India to receive the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding. Indiraji asked me to suggest a gift our government could give to honour him. I suggested that of all the Indian musical instruments, Shārdā Ma’s veena is the one which best symbolizes our ancient Vedic culture. Yehudi Menuhin is a maestro of the violin, which is a stringed instrument, thus the veena would be appropriate. Indiraji therefore gave him a rudra veena.’

‘Towards the end of 1976, Indira Gandhi visited me here. That was during the Emergency period. One day, to my shock, a large number of policemen appeared out of nowhere and told me that the prime minister was coming up to meet me. They conducted a quick security sweep of the entire building and this apartment. I had no idea what was happening outside, but I later learnt that the area had become a high-alert zone. Within a few minutes, Indiraji came.

‘Despite her being so busy, that too during the Emergency, she patiently sat and chatted with me for quite a few minutes. After exchanging some pleasantries and reminiscing about our Delhi days, she asked me if I would agree to allow my surbahār playing to be recorded under the auspices of the NCPA. I politely refused.’

‘She informed me that she was awarding me the Padma Bhushan. She asked me if I would come to Delhi and attend the ceremony. I apologized, but told her I no longer left the house and these awards meant nothing to me. Amused by my reply, Indiraji laughed.’

‘She then surprised me by asking my opinion of the Emergency rule. I candidly told her, “I don’t have much knowledge about politics, but my personal opinion is that what you have done is very wrong.” Indiraji didn’t react. After a few minutes of contemplation, she left. Before leaving, she gave me this framed, autographed photograph of her.’

‘That was the last time I met her and I never heard from her again. Within a month or two, Indiraji withdrew the Emergency rule and declared general elections. The government of India then sent me the certificate of the Padma Bhushan award by registered post.’

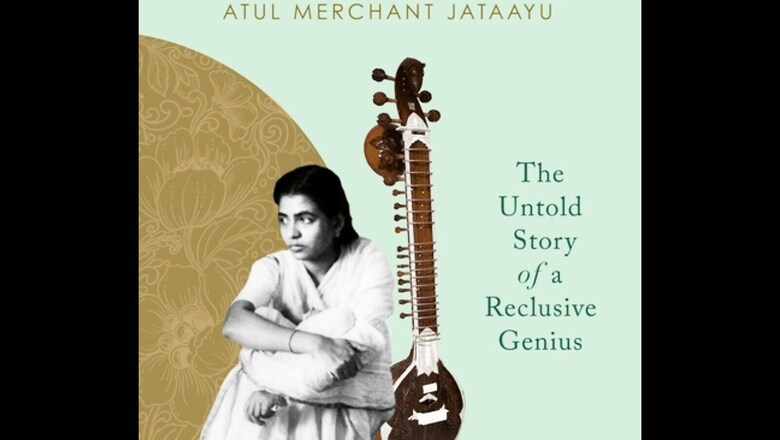

This excerpt from Annapurna Devi: The Untold Story of a Reclusive Genius by Atul Merchant Jataayu has been published with the permission of Penguin Random House India.

Read all the Latest Opinion News and Breaking News here

Comments

0 comment