views

One of the first casualties of Sanskrit learning in Tamil Nadu was a traditional Gurukulam located in the ancient Kallidaikurchi Agraharam falling under the jurisdiction of the Tirunelveli district. It was situated on the banks of the sacred Tamraparni river sanctified by countless generations of Vedic scholarship and whose glories the 19th-century Carnatic music composer, singer and saint, Muthuswami Dikshitar never tired of singing. Kallidaikurichi is just 70 km from Kanyakumari. And Kanyakumari is today a Christian-majority city.

Around 1920-22, the Dravidian goon squad (mentioned in the previous part of this series) rudely descended on Kallidaikurchi on the pretext of raising an objection to the funds allocated for the Sanskrit College therein.

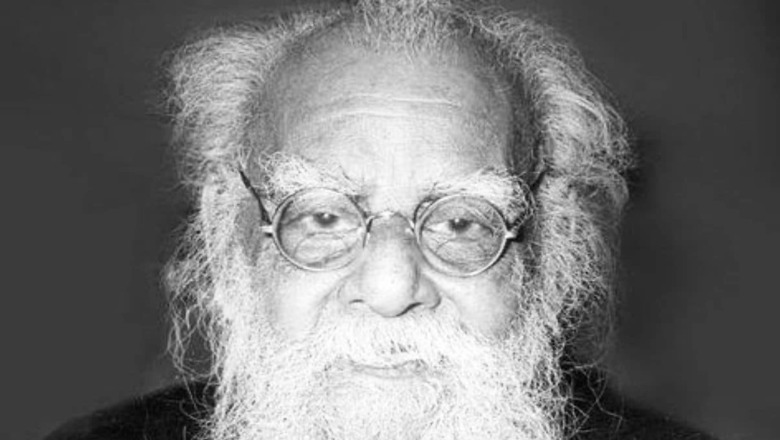

The squad was led by E.V. Ramaswami Naicker and his trusted lieutenant, P. Varadarajulu Naidu. Through a series of relentless, pitched agitations lasting about three years, Varadarajulu Naidu exhorted the non-Brahmins as follows: “[the Gurukulam] is a direct challenge to the non-Brahmins and…this is the time for the pure Tamilians to vindicate their honour!”

Naidu then embarked on a blitzkrieg of such incendiary speeches against Brahmins in his statewide campaigns. His campaign stops included Tirunelveli, Mayavaram, Salem and other important cities and towns.

The outcome was entirely along expected lines: violent street riots broke out wherever he went, and the Brahmin community ultimately came to the negotiating table.

The maiden victim of the negotiation was V.V.S. Aiyer, the head of the Kallidaikurichi Gurukulam, who resigned.

With that, E.V. Ramaswami Naicker and his Dravidian ‘warriors’ had tasted blood. By 1925, Naicker decided that Mohandas Gandhi had proven to be an insurmountable roadblock in his unstoppable march towards unhinged Dravidianism. He quit the Congress and formed his own organisation of Dravidian stormtroopers.

Around this time, the ‘supreme’ status of the Tamil language had acquired almost unchallengeable proportions. Throughout the Tamil-speaking regions, feverish efforts were underway to invent a new political vocabulary, which was to be “purely Tamil” — i.e., completely shorn of any Sanskrit influence. In hindsight, it appears that scores of eminent men in public and academic life of that period had completely fallen for this dubious theory. Among the more high-profile victims who fell for this Tamil supremacy hoax was the former Diwan of Mysore, V.P. Madhava Rao. Here is how the scholar Irschick describes it:

“At a Madras Congress Provincial Conference held at Cuddalore in 1917, V. P. Madhava Rao, a Maharashtrian Brahman from Tanjore, pointed out that those who had spoken in Tamil at the meeting had demonstrated conclusively ‘the capacity of the Tamil language for the expression of ideas connected with administration, with law, and politics’.”

From one perspective, it was the need of the hour to develop a native political vocabulary as a means to rouse the masses against the alien British rule. However, in the context of Tamil Nadu, this vocabulary would mean handing over ammunition to linguistic and racial separatism for which there was no basis in India’s history. This is precisely what the likes of V.P. Madhava Rao did when he gave his endorsement to an alleged Tamil linguistic superiority. The other notable name was that of “Right Honourable” V.S. Srinivasa Sastri who eventually capitulated to the demands of Tamil linguistic chauvinism.

Exactly a year later, Varadarajulu Naidu launched another multi-city political tour. We can again turn to Irschick for what occurred next: “Varadarajulu Naidu [in his political tour]… used only Tamil, and he effectively proved how valuable it could be as a political tool. At Negapatam [Nagapattinam], his first triumph, he attracted a huge crowd of workers from the railway shops. At Madura he spoke to millworkers — so vigorously, in fact, that he was arrested. He was convicted on the evidence of shorthand transcripts of his Tamil speeches…”

Meanwhile, in the same year that Ramaswami Naicker established his own political front, a Tamil scholar named M.S. Purnalingam Pillai, who was also secretary of the Tamil University Committee, “moved at a Justice [Party] Confederation in December 1925, that the government should…grant to the Tamil districts a university to encourage the ‘growth of the Tamil language’, as well as the development of ‘historical consciousness among Tamilians’”.

His chorus was joined by T.N. Sivagnanam Pillai (Justice Minister of Development), who also demanded a separate Tamil University and alleged that Madras University was insulting Tamil by concentrating on Sanskrit, over which the “Aryas-Brahmins” held a monopoly.

To be sure, the demand for a separate Tamil University was as old as 1916. After sustained activism, the university was established largely due to the decisive largesse bestowed by Sir Annamalai Chetti. In 1929, the Annamalai University was founded in the sacred temple town of Chidambaram.

However, it would still take more than two decades before the fate that befell Sanskrit learning in Thanjavur and the Kallidaikurchi Gurukulam would befall on other centres of Sanskrit learning in Tamil Nadu. It was just a question of when and not if.

(To be continued)

The author is the founder and chief editor, The Dharma Dispatch. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment