views

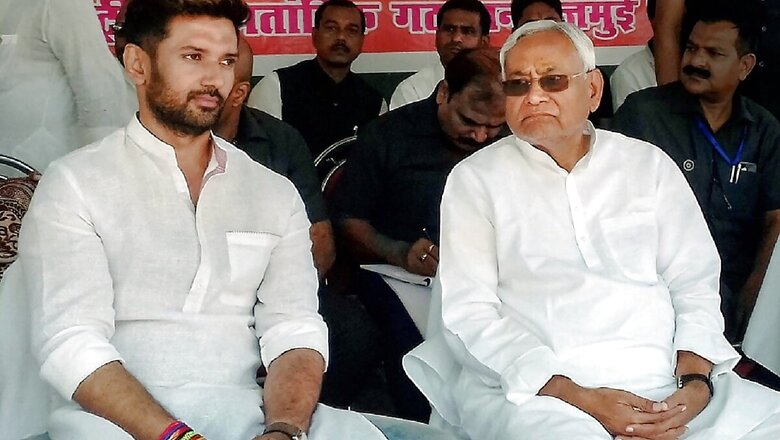

The preface to the unfolding Bihar 2020 poll story has become very intricate with first the Lok Janshakti Party (LJP) walking out of the ruling National Democratic Alliance (NDA), and then its leader Ram Vilas Paswan’s demise. However, the loss of patronage from the first family of Dusadh community (not to be confused with another Dalit community identified as Pasi) of Bihar may not necessarily paint an abysmal picture for state Chief Minister Nitish Kumar.

Those who follow the politics of the country’s politically most convoluted state, would recall that Nitish Kumar had initiated the social engineering process to create the voting vertical of Mahadalits to counter the influence of comparatively powerful communities of Chamars, aligned for a longtime with Congress (largely due to the presence of Babu Jagjiwan Ram and his daughter Meira Kumar) and now with Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), and Dusadhs, where Ram Vilas Paswan’s influence was taller than anybody else.

Lack of trust between Nitish Kumar and Paswan (made so overt by Chriag Paswan) is not about personal preferences but embedded in the social-caste structure of the state. To illustrate the point, one could recall the infamous Belchchi massacre of 1978, which proved to be a turning point in the revival of the fortunes of then ousted Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and the Congress party.

She had taken an elephant ride to reach the village where Dalits (read Dusadhs) had been killed by landlords. Belchhi was among one of the severest massacres of Bihar’s history of social conflict. It was a fallout of the resistance by the group of agricultural labourers belonging to the Dusadh community to the ways of the Kurmi landlords.

Belchchi falls in Nitish Kumar’s home district of Nalanda and he knows well that Dusadh-Kurmi electoral union is next to impossible given the history of social conflict between the two communities. Nitish himself comes from a Kurmi landowning family and enjoys a loyal vote base among his caste voters.

Dusadh community is given to the rebel ways as they had found early employment with the British regime as village chowkidars (watchmen) and messengers. They had also found employment with the army of the East India Company.

Given their traditional vocation of pig rearing, Dusadhs could never reconcile to the presence of Muslim elements in the company army. Thus, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi makes an appeal to the chowkidars, somewhere he also identifies with the members of the Dusadh community whose electoral presence in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh is well-established.

Keeping on the history of social conflicts in Bihar, the Dusadhs, while remaining averse to the Kumris, have broken bread with the other powerful intermediary castes like the Yadavs in their struggle against the upper-caste landlords. The Naxalite uprising of Bhojpur in 1960s had Dusadhs and Yadavs as the main cadres with Ramnaresh Paswan and Rameshwar Ahir as leaders.

In another infamous caste massacre, Senari (1999), the Maoists had used blunt weapons to kill 34 members of the land-owning Bhumihar community. Those convicted in the brutal murder, including the 10 who were awarded death sentence, belonged to the Yadav and Dusadh communities. Even in the infamous Bhagalpur riots (1989), while the main perpetrators were the rioters from Yadav community, they had tacit support of the Dusadh community. To put the other way round, none from the community rose to defend the victims from the minority community.

Given the social structuring and their impact on the voting patterns, Nitish Kumar right during his first term as the Chief Minister created the electoral vertical, as mentioned earlier, of the Mahadalits. In 2007, soon after he had consolidated his position as Chief minister, Nitish Kumar set up the State Mahadalit Commission to recommended inclusion of extremely weaker castes from the list of Scheduled Castes.

Dusadhs and Chamars were kept out of the list of castes recommended by the commission to be categorised as Mahadalits. The political design of this social decision became known ahead of the 2010 assembly polls, with a slew of government schemes announced to woo Mahadalit voters.

Nitish Kumar made no bones about ’empowering’ these castes and reaped a rich electoral harvest with Paswan’s party, which had emerged as a force in 2005 polls, being completely routed. Till date, despite the Mahadalit Commission coming out with two more recommendation, Dusadhs are still to find place in the Mahadalit list, though Chamars have made it.

Nitish Kumar took this social structuring further by enforcing prohibition in the state after the 2015 polls. At the time, Nitish Kumar government decided to bring in the prohibition law, the state was raking in Rs 4,000 crore annually as excise revenue. This is the huge price he has paid to build a caste-neutral political constituency of women.

Belonging to the Kurmi caste, as mentioned earlier, which despite being part of the other backward castes (OBC) mosaic is not populous enough to hold a leader on its own strength, Nitish Kumar in the past 15 years has worked out creating newer vote verticals as Mahadalits. No wonder the mascot of the Prohibition Movement in the state Girija Devi is a woman from the Mushar community, a Mahadalit caste in both word and spirit.

Coming back to the exit of the LJP from the NDA, Chirag Paswan precisely sees not much space for his caste in a Kurmi-propelled combination. His caste’s historical ‘social distancing’ from the Muslims, however, makes the LJP leader comfortable in the company of the Bharatiya Janata Party. It’s an intricate caste matrix, which only time would decipher.

Read all the Latest News and Breaking News here

Comments

0 comment