views

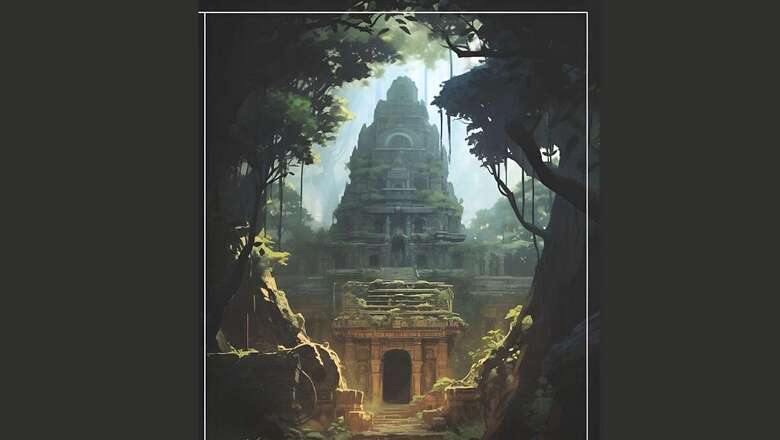

Since the dawn of civilisation, humans have started using the materials available in their vicinity to make their lives safe and comfortable. One such material was stone. It is found in abundance everywhere, and every civilization has made full use of it. Humans’ love for the stones has never ceased since then. They first used them as primitive tools to kill the animals and their enemies. They also used these tools for cutting and breaking hard surfaces. With the passage of time, they started embellishing them, making full use of their imagination and worldview. Soon, they needed someone to give them hope and protect them from natural elements, ferocious animals, and enemies. They could not find a better and more permanent material than stones to house their gods.

Pre-Historic mounds

There has always been a strong human desire to honour the dead, to communicate with them beyond their graves, and to keep their memory alive. Creating a round mound was the most economical method of creating a massive visual impact and humans all over the world went on to create them. The next easiest method was to create a dolmen (a flat roof stone over two vertical stones). There are 2,200 such megalithic sites in South India alone. These were the most ancient temples of India.

To honour the gods, ancient kings conducted various rituals such as yagnas, Ashwamedha, and Rajsuya, which also served to assert their imperial authority. Agni, considered the most ancient, transportable, and renewable representation of the Divine, was central to these ceremonies, with agni-kunds (fire altars) used for purifying palaces, households, or entire kingdoms.

Around 5,000 BCE, during the Saraswati-Ghaggar civilisation, Hindu temples resembled open-air agni-kunds, with sacred symbols on raised platforms and offerings made to the fire. These altars were not permanent but constructed in temporary ritual arenas called yajnashalas. One significant ritual from this era was the Agnicayana, a special prayer meant to create an immortal figure for the sacrificer, transcending the fleeting nature of life, suffering, and death. This ritual involved building a fire altar with specific bricks laid out in a detailed pattern, accompanied by specific mantras in five layers, with the sacrificial layer on top. Once the rituals were complete, the site was burned and left abandoned.

One seal, known as Pashupati, gained prominence during John Marshall’s 1928 excavation. Marshall identified the figure as an early representation of Shiva and suggested the existence of a Mother Goddess cult based on several female figurines found. Similar seals depict a headless fertility goddess with ample bosoms and vulvas, later dubbed Lajja Gauri. The reverence for motherhood was considered a divine tradition, possibly an ancestor of the Devi cult. The presence of goddesses dispels any notion of a male-centric or patriarchal society, suggesting an egalitarian ethos.

Despite the discovery of ruins such as granaries, bathhouses, community centres, and ports, no temples have been unearthed at Harappan sites where these statues or seals were discovered.

Even during the later Vedic period around 1,000 BCE, many historians, including renowned art historian Vasudev S. Agarwala, asserted that Hindu temples did not exist, based solely on archaeological evidence. Their conclusions are influenced by the fact that scriptures such as the Vedas and Upanishads do not mention temples. While the Ramayana and Mahabharata do reference Devalayas, the specifics of their structure, design, and materials remain unknown. Furthermore, the lack of archaeological evidence for these Devalayas complicates investigations. Prayers during this period were generally more private.

Nonetheless, there are numerous references to individuals praying to deities, particularly Shiva and Vishnu, retreating to caves, mountains, and forests for penance, undertaking pilgrimages, and manifesting the deities themselves. For instance, the Mahabharata contains an entire chapter on a pilgrimage called Tirtha-yatra-parvan. The primary object of worship at this time was agni (fire), symbolising God. In the Ramayana, Lord Rama establishes a lingam of sand at Rameswaram for praying to Shiva, but no temple is mentioned. It is difficult to imagine Hindus without their temples, which are so central to their identity today. Thus, the history of Hinduism can be divided into two eras: Nigama, without temples, and Agama, with temples.

Sometime after 1000 BCE, archaeological evidence indicates that Hindu temples were initially more like open-air shrines, featuring sacred symbols on raised platforms and offerings made to fire. These symbols were mainly aniconic, with a notable absence of material representations like trees, animals, or humans. Later, naga shrines emerged, likely out of respect or fear for snakes in agricultural fields, as many people must have been bitten while tending to crops. The guilt from killing numerous snakes while establishing villages or farming might have spurred the creation of these shrines. During this period, Agni shrines also appeared, where fires were lit under the sky for offering oblations. Subsequently, shrines dedicated to Yakshas, as mentioned in the Rig Veda 4.3.13, became common. Temples for spirits, both benevolent and malevolent, who inhabited trees, mountains, rivers, and other sacred places, also proliferated. Additionally, temples for Bhu-devi, the earth goddess, were constructed to enhance crop production as agriculture became central to human sustenance.

In the second stage, railings were constructed around the shrine’s perimeter to prevent trespassing by animals and hostile humans. Initially made of wood, these railings were later built from stone to strengthen the protective barriers. In ancient times, they enclosed a vedi, which was a raised shrine or agni-kund (fire platform). For instance, in Nagari, Rajasthan, there is a platform with railings made of massive stone blocks, standing 8 feet tall, reminiscent of Stonehenge in Britain. Some inscriptions in Brahmi refer to it as ‘Narayan Vataka.’ The design of these railings significantly influenced Buddhist monuments like Sanchi and Amravati. Even today, in new pagodas, the railings, known as vedika, remain a prominent feature.

The earliest temples before the 3rd BCE:

- A raised platform with or without a symbol

- A raised platform under an umbrella

- A raised platform under a tree

- A raised platform enclosed with a railing (Vedika)

- A raised platform inside a pillared pavilion

- Initially, wood was used, but later on, stones were used

Meanwhile, Buddhists began replacing Yaksha idols with Bodhisattvas. To protect the idol from the elements and show respect, they started placing a Chattri (parasol) over it, as seen with the Bodhisattva of Mathura, now housed in the Sarnath Museum.

Eventually, the idol was enclosed by three walls and a carved roof, known as a gandhakuti (perfumed chamber), with a lotus always present on the roof. Buddhists considered this the earliest garbhagriha. After the Vedic era, as Hindus performed their daily worship and rituals in their homes or open-air shrines, they observed the increasing number of Buddhist shrines around them. Consequently, Hindu worship began to take place in covered shrines made of more permanent materials, imitating these monuments.

Alexander’s invasion in 326 BCE marked a significant turning point in the evolution of Indian temples. His soldiers, including many sculptors and artists, stayed behind, leading to a cultural exchange that enriched the architectural concepts of Buddhist and Hindu temples. Indians, with their receptiveness and open-mindedness, adopted and adapted these new ideas, resulting in strong similarities between Greek architecture and the earliest Hindu temples.

Temples, therefore, marked the transition of Hindu dharma from the Vedic rites of ceremonial sacrifices to the faith of Bhakti and devotion to favourite gods. Temple architecture, construction and mode of reverence were administered by several ancient Sanskrit scriptures called agamas, which deal with individual gods. Over a period of time, substantial innovations crept into the architecture, traditions, rituals and customs of temples in different regions of India, giving each a distinct look and feel.

The above article is an edited extract from Amit Agarwal’s book, ‘Temple Treasures: A Journey Through Time’. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment