views

“We speak of world movements and have a fair acquaintance with the principles and details of Western life and thought, but we do not always sufficiently realise where we actually stand today and how to apply our bookish principles to our situation in life. […]

We talk – a little too glibly perhaps – of a conflict of the ideas and ideals of the West with our traditional ideas and ideals. In many cases, it is confusion rather than a conflict, and the real problem is to clear up the confusion and to make it develop in the first instance into a definite conflict. The danger is in the complacent acquiescence in the confusion. The realisation of a conflict of ideals implies a deepening of the soul. There is conflict proper only when one is really serious about ideals, and feels each ideal to be a matter of life and death. We sometimes sentimentally indulge in the thought of a conflict before we are really serious with either ideal.”

– “Swaraj in Ideas” (1929), Krishna Chandra Bhattacharya

Nearly a hundred years ago, Acharya Krishna Chandra Bhattacharya, India’s pre-eminent modern philosopher from the early 20th century, had given a discourse named “Swaraj in Ideas” before his pupils at Hooghly College. In this discourse, he warned us of several pitfalls in the business of intellectually navigating through a modern world, where ideas and ideals of one’s own national identity are bound to interact with those from the world outside. In the process of showing where such pitfalls may lurk in, in a language and in a style that is strikingly lucid and persuasive, the Acharya especially highlighted two things: first, the danger of not sufficiently realising how and where to apply certain principles or ideas that we may have learned in our schools; and second, the folly of indulging in glib talk about a conflict between the ideas and ideals of the West and those of our own tradition, when in reality there may not be a real conflict but only confusion regarding the ideas and ideals involved. The Acharya’s warnings proved prophetic in a recent predicament involving an international film awards event and our mixed reactions to its outcomes where India was concerned.

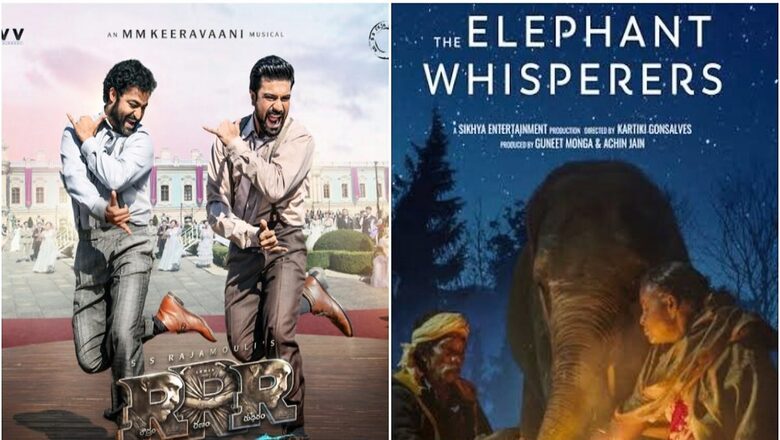

Not one, but two Indian entries clinched the winner’s title at this year’s Annual Academy Awards, which is popularly known as the Oscars. At this 95th edition of the Oscars, held in Los Angeles, USA, the Telugu song ‘Naatu Naatu’ from S.S. Rajamouli’s 2022 blockbuster nationalist drama ‘RRR’ made it to the top in the ‘Best Original Song’ category, and so did Kartiki Gonsalves’ ‘The Elephant Whisperers’ in the category of ‘Best Documentary Short’. Naturally, many Indians found themselves elated at the newsbreak of this double success.

That elation is hardly a matter of surprise. But what is indeed a little surprising is that some Indians are expressing disgruntlement over the celebratory mood displayed by their fellow countrymen. And the reason why they’re disgruntled over this turn of events is – you’re in for another surprise – not their disagreement over the award choices made by the Academy’s voting members. Instead, it is a concept that this disgruntled section has turned into a slogan by adopting a crude reductionist approach to understand and apply. It is a concept that has only recently gained traction among this unhappy section, which consists mainly of social media commentators and a few writers, who claim to be speaking/writing from a ‘Hindu standpoint’.

As is the wont of social media opinion peddling, users find slogans to be a useful tool – because they’re simplistic, they don’t invite or even require people to do much thinking (or any thinking at all); and thus, social media users, relieved of the necessity to use their mental faculties, can quickly conjure around them a virtual mob of followers who may hit ‘like’, ‘share’, and ‘subscribe’ at the drop of a hat. After all, isn’t that what commentating on social media is about, for the most part? Be that as it may, in this particular instance, the slogan being spouted by the aforementioned section of social media commentators, who are disgruntled over Indians celebrating the success of Indian entries at the Oscars, is the voguishly oversimplified term ‘decoloniality’.

Vaguely understood by the sloganeers themselves, decoloniality happens to be a theoretical concept which encapsulates a culture-specific way of being and knowing, and which provides a radical alternative to the one that is forcefully imposed upon much of the world by Euro-American colonialism throughout history. Decoloniality, thus understood and practised, can become a key instrument in dismantling the hegemony of the colonialist Euro-American way of being and knowing, which has a universalistic pretension of an almost fanatic nature, and which seeks to dominate the minds and bodies belonging to every other culture on this planet. Each erstwhile (or presently) colonised nation or culture that has somehow managed to survive the onslaughts of colonialism in one form or another, has the potential to evolve and offer its own version of decoloniality, based on its peculiar historical experience and its national character.

Like some African and Latin American nations with a really long and harrowing experience of European colonialism, present-day India, too, has evolved its own distinct form of decoloniality. But India had to withstand a double whammy of successive colonialist projects: at first, she faced a particularly traumatising Islamic rule across various large parts of the Subcontinent, followed by the British colonial rule that engulfed almost the whole country and invaded every little aspect of Indian life. Barring a few African nations, no other nation or culture had to undergo such a distressing and prolonged experience of political and cultural colonialism.

However, there’s still a silver lining to this dark period’s history. Due to the sheer historical and geographical magnitude of the twofold colonial impact, India’s resistance has accordingly evolved to be much more layered and richer than any other form of anticolonial resistance anywhere in the world. In fact, other nations have drawn inspiration from it to resist and change the dehumanising status quo that colonialists sought (and, in several instances, are still seeking) to perpetuate. Add to this India’s civilisational legacy, which itself had evolved through millennia of pre-colonial Indian history, and through multiple socio-cultural revolutions occurring at both precolonial and colonial periods, it helped India surge boldly ahead into the future, braving all sorts of odds along the way. In the process, the Indian civilisation has wrought for itself a wonderful power of assimilating differences into its mainstream, without allowing any fundamental changes to occur in its character.

These evolutions have taken a long curve through India’s vast historical timespan – emerging rather slowly through the first fifteen centuries of the common era, building its groundwork upon the shoulders of saints and warriors who defended dharma in the face of Islamic invasions and proselytising efforts – but it picked up a highly accelerated rate of growth only thereafter, reaching a climax in the 19th and 20th centuries during the British colonial period.

Moreover, this homespun Indian decoloniality has been shaped by historical circumstances and cultural currents that are not exclusive to India, a country which has constantly interacted with various nations of the world in these slow-paced intervening centuries, before reaching an apogee of cross-cultural transactions, especially with Europe and America, in the last two hundred-odd years. Several world historical events, and the influence of exemplary leadership in such events – including the French Revolution, the American Revolutionary War, the Italian Carbonari Movement, the Unification of Italy, the shaping of the modern German state under Bismarck, the Irish Revolutionary Movement, and the Russian Revolution – left a deep imprint upon the best minds of India in those two centuries of tumultuous political upheavals around the world.

Despite all these strong currents of influence rushing in from all directions, India in the 19th and 20th centuries has attempted, even more vigorously than she has done in the past, to assimilate those external elements into her time-tested civilisational character. The special contribution of the dynamic modern era consisting of the last two centuries is that it gave India’s own version of decoloniality a very definite and robust shape, as against an amorphous, disjointed decolonial narrative of the era that immediately precedes it. India in those two critical centuries was blessed with some extraordinary minds and personalities in the fields of religion, education, philosophy, politics, the arts and the sciences: viz., Raja Rammohun Roy, Pundit Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, Thakur Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, Swami Vivekananda, Rabindranath Tagore, Sri Aurobindo, Krishna Chandra Bhattacharya, Mahatma Gandhi, Jagadish Chandra Bose, Abanindranath Tagore, Ananda Coomaraswamy, Nandalal Bose, Sri Anirvan, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, Ramachandra Gandhi, and many others. It is thanks to their exemplary lives, their self-effacing, benevolent actions, the profundity of their thinking, and the clarity of their articulation, that the assimilative decoloniality of Modern India was made future-ready for India herself, and for the rest of the world, even before the twentieth century came to a close.

Thus, a careful perusal of Indian history reveals that centuries of life-threatening and all-sacrificing struggle started bearing fruit with a cultural revolution in the nineteenth century, which in turn gave rise to a bold new anticolonial political revolution at the very beginning of the twentieth. And it is mainly due to the momentum generated during that revolutionary era, that India has managed to maintain a connection, howsoever thin, with her living but endangered civilisational inheritance till this day through thick and thin, through all the deafening tumult of historical-political-social upheavals, and despite having suffered two prolonged, severe bouts of foreign colonial rule at the hands of various West Asian and European nations.

Precious little of this historical complexity is reflected in the popular discourse that reduces decoloniality to a mere slogan. Slogans as such are not necessarily bad; they help you get excited over things that are sometimes worth getting excited about, but there is a kind of unidirectional inertia of motion attached to the business of sloganeering, that ends up zombifying human beings by stripping them off their God-given power to reflect.

Having closely followed the popular discourse arising out of a supposedly nationalist coterie, it seems to me that an ill-understood, ill-digested, and childishly flawed perception of decoloniality, as well as an equally ill-conceived area of its application, is lately being used as a bundle of sticks to beat some unsuspecting and rather easy targets with. The latest of such victims is the Indian crowd celebrating the success of Indian films like ‘RRR’ at various competitive platforms overseas. Their fault? Merely that they’re elated at the success of these Indian films at some foreign awards ceremony and are celebrating the same.

Little do our decoloniality sloganeers realise that competition, of any kind and on whatever platform, does have the inherent tendency to build up a kind of intense anticipation around it, which should be dissipated, and can only be expressed, through a momentary outburst at one’s success or failure. Not everyone happens to be the stoic sthitaprajña that the Bhagavad Gita presents as an ideal – least of all our decoloniality sloganeers. And that is by no means a hopeless scenario; even competition can usher in some good if it is fairly conducted, and if it generates a healthy desire in the participants’ minds to excel at their craft. The competitive spirit that is fundamental to the concept of sporting events is a case in point. Will our decoloniality sloganeers now decry international sports as well? Will they denounce the various prestigious recognitions that Indian cricket teams, Indian hockey teams, Indian football teams, Indian athletes and sportspersons have over the years gained, and still continue to gain, through their hard work and performance in competitive events organised internationally, or by a foreign country exclusively, such as the Olympics or the US Open tennis tournament?

How I wish these deprecators of the Oscars had instead directed their ‘critical lenses’ at the very idea of introducing competition in the field of cultural content production – like the great poet Rabindranath Tagore had once done in his essay “Brahmana” to criticise competition as a fundamental driving force of the socio-political machinery in Europe. That would at least have been a much more genuine critique of the economy of such show businesses that masquerade as measures of cultural excellence – something patently foreign in the traditional cultural domain across civilisations, and especially so in terms of Indian cultural sensibilities.

I also wonder if these geniuses have ever stopped to consider the fact that these Oscar-winning Indian films are now going to attract more attention, and so will the works of those who have been involved in the making of these films. I for my part hadn’t even heard the name of The Elephant Whisperers before it won the coveted prize; and it is only after the news broke that I noticed its presence on Netflix, despite being a regular visitor to the Netflix website. When I finally did watch this short documentary film, I was struck by the affectionate depiction of what was a classic vignette of a patently Indian, Hindu way of life integrated with Nature in perfect harmony. While watching the documentary, I was reminded of Tagore’s utterance, made in deepest spiritual conviction, to the effect that God is ever-present in his life by entering his heart through his relations – father, mother, brothers, wife, his friends and children, indeed his entire family – when Bomman, one of the human protagonists of the documentary short subject, observed in all sincerity and simplicity: “I am proud of being both a priest and a mahout. Both bring me immense happiness. We pray to Lord Ganesha. Seeing an elephant, to us, is equivalent to seeing God. God and elephants are one for me. The way I serve God is the same way I serve the elephants. We take care of Raghu [an elephant calf, another protagonist from the film] every single day, which in turn, puts food on my table every day. This is God’s presence in my life. Without him, we’d have nothing.” That is the whole essence of Indian civilisation’s attitude to life, summed up in a fraction of a sequence in ‘The Elephant Whisperers’. God bless the film, its characters and its makers; and God bless the Oscars for thrusting such a film into the limelight. Indian decoloniality – the Indian way of being and knowing – will spread across the world through such films, far wider and far more effectively, than any sulky, preachy sloganeer can ever dream of doing.

And then there is ‘RRR’, that operatic celebration of the Indian nationalist freedom struggle, its revolutionary spirit, its dharma-based angle of justice and respect for every living being, as also the celebration of characteristically Indian loyalty towards family, friends, community, and homeland. Do I personally think the song ‘Naatu Naatu’, for which the film got the Academy Award, is the best thing about the film? Heck no; neither is it my favourite song from the film (and probably not of M.M. Keeravani’s either). With my sensibilities, ‘Komuram Bheemudo’ appeals to me deeply, but the international audience seems to have gone gaga over ‘Naatu Naatu.’ But that hardly matters in the larger scheme of things. Thanks to the Oscars recognition of this one element of ‘RRR’, more and more people from various countries, of different generations, and of diverse tastes are now going to sit through this modern epic, and might as well take note of several other films made by S.S. Rajamouli. And in the process, they’d perchance soak in some of the ethos of Indian civilisation that so obviously pervades his works. Is that a good thing or a bad thing for India, for Indian civilisation and Indian nationalism? The answer is, I think, obvious. I can see no downside to an increasing amount of global attention being directed to Indian cinema, and despite my best efforts at scepticism, I can think of only prosperous pictures that such attention can result in. More awareness about India, her history, and her unique way of being and knowing, is likely to build up a positive image of India and Indians around the globe.

There’s another side to the farcical pontificating done by our blessed beloved sloganeers. Apart from reducing a profoundly important concept like decoloniality to a mere slogan, the air of self-righteousness being put on by this jargon-happy coterie of superficial social media commentators is becoming totally nauseating by the hour. Their oversimplified line of ‘reasoning’ goes like this: because we are presently ‘decolonising’ ourselves, we no longer need any kind of validation from the world outside for what we do! Taking a step further into their murky discourse, not only do the decoloniality sloganeers claim that international recognition of indigenous cultural products is irrelevant because India is now ‘decolonising’ herself, they also proclaim to us poor benighted people their judgment that, since such recognition does not matter, those who attach any amount of importance to such trifles, are fundamentally lacking in respect for, or faith in, indigeneity. This sorry excuse for logic could have simply been dismissed as an object of ridicule, had the sloganeers not claimed for themselves a moral high ground right on the basis of this pitifully faulty argument. And it is precisely because of this sort of one-upmanship practised by our decoloniality sloganeers, dwelling in their respective social media echo chambers, smugly oblivious of their dopiness, that the whole thing feels utterly obnoxious.

But let us stick to discussing the quality of thought displayed by their arguments. Stumbling upon such stunning products of woolly thinking, one feels dumbstruck at first. When the benumbing effects of this gloating smugness wear out a little, one starts wondering: whence this complacency, this sense of being contemporary witnesses – even active participants – of some imaginary revolutionary present epoch of ‘decolonising’, could have crept in into the consciousness of Indians living in the 2020s, in the first place? Living in this era of abject surrender by India to neo-colonial modes of being and knowing (which, by the way, are nothing but the old wine of eurocentrism presented in a new, sturdier bottle) in every single sphere of human culture, from politics to religion to family life, it is a wonder that one could still feel so overconfidently certain and so complacent about being ‘decolonised’. Could it be true that these blessed sloganeers would like themselves and their social media followers to imagine that this ‘decolonising’ process just started the other day when one of them woke up to catch their 8 AM bus to work? Or maybe it started with the onset of the COVID pandemic in 2020, when folks took to performing Surya Namaskar regularly (only to slacken their newfound enthusiasm for yogic regularity, or drop the practice altogether, with the return of normalcy), and when they learned the trick of smattering grammatically awkward Sanskrit terms all over their usual linguistic medium of thinking, speaking, and dreaming, namely, English? Or maybe ‘decolonising’ had started f-a-a-a-r back in the Indian civilisational scale of time – for example, in 2014, perhaps?

As a matter of fact, Indian decoloniality has been formulated and articulated in precise terms during the last two centuries, its blueprint and the direction it ought to take meticulously worked out in the writings of thought leaders whose names have been already mentioned. At the risk of sounding repetitive, I must highlight the point that the project of charting out this unique modern-day version of Indian decoloniality had reached its climax in the 19th century, it had all the blessings of the centuries preceding it, and it was completed by the 20th century with a great and almost sacred sense of urgency. But like the River Saraswati of yore, a river that is central to the story of our great civilisation’s past, the Indian decoloniality project has unfortunately lost its way in the desert sand of present-day democratic electoral politics.

What remains to be done is to educate ourselves in the literature of this well-formulated, sharply-articulated Indian decoloniality, and bring back the Indian way of being and knowing to the centre stage of our public and personal consciousnesses. It has to be done, if at all, with a greater and more sincere sense of urgency than that with which the main architects of the project took it up in the early 19th century, all the while keeping in mind that it’s already been very late in the day.

What we should also keep in mind is that Indian decoloniality, this Indian way of being and knowing, does not at any point seek to cut the Indian off from the outside world. To do so is to damn ourselves to a dingy chamber of parochiality, the kind which Swami Vivekananda had warned us against in a famous 1893 speech at the Parliament of World Religions in Chicago. In that speech, the venerable Swami, who was a formidable organ voice of Indian civilisation in this Modern Era, told the story of a frog who lived in a well all his life; and by virtue of living all his life in the well, it had come to the conclusion that “nothing can be bigger than my well; there can be nothing bigger than this; this fellow [another frog that came visiting him from the seaside] is a liar, so turn him out.”

I can only hope that we, mired as we presently are in our contemporary political exigencies and our little games of self-seeking competitive pursuits, don’t end up being a Kūpa–maṇḍuka, the frog who lived in the well, in the name of a sloganized, reductionist, and stunted decoloniality.

Sreejit Datta is an educator, researcher and social commentator, writing/speaking on subjects critical to rediscovering and rekindling the Indic consciousness in a postmodern, neoliberal world. Views expressed are personal.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment