views

Paolo Sorrentino’s films can be overwrought, grotesque and uneven but they are rarely not alive.

His latest, The Hand of God, is a catalog of wonders of miracles both banal and eternal. The glittering night vista of the Naples harbor. The soft thump of a motorboat across the water. The naked body of a beautiful woman sunbathing.

Sorrentino’s Oscar-winning masterpiece, The Great Beauty, too, was crowded with awe and sensation as it rambled around Rome. In The Hand of God, which Netflix opens in theaters Wednesday and begins streaming Dec. 15, the director has turned south to his hometown for an autobiographical film based on his 1980s childhood. Still, Sorrentino, a melancholy but ecstatic filmmaker with an eager, energetic camera, is in much the same mood here, finding divine splendor in the everyday and the profane.

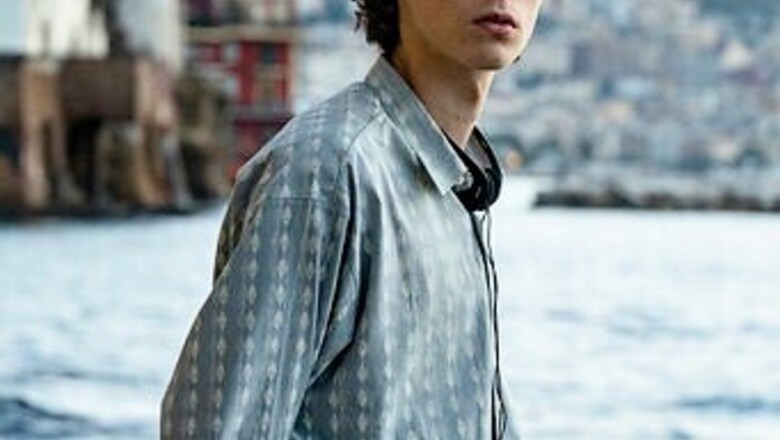

The Hand of God, winner of the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival and Italy’s Oscar submission, is a more personal detour for the 51-year-old Sorrentino. Its exaggerated cast of characters pull from his own family. Our protagonist, standing in for the director, is the teenage Fabietto Schisa (Filippo Scotti), a timid young man with a ball of curly hair and Walkman headphones draped around his neck. He’s mostly an observer to the family circus around him: his charismatic father Saverio (Toni Servillo, a Sorrentino regular), his prank-playing mother Maria (Teresa Saponangelo, terrific) and his aspiring actor brother Marchino (a tender Marlon Joubert).

There are other key figures, too, like Fabietto’s gorgeous aunt Patrizia (Luisa Ranieri), whose suspicious husband is abusive, and Diego Maradona, the soccer legend whose unlikely acquisition by Napoli is rumored at the film’s start. When he does actually arrive, it’s as if straight from heaven. (It’s a feverish time brilliantly documented in Asif Kapadia’s Diego Maradona.) Both Patrizia and Maradona are like phenomena in Fabietto’s life, which here seems like a cartoonish picaresque until a tragedy jolts him and The Hand of God into a different realm.

We’ve had of late quite a few portraits of filmmakers as young people Joanna Hogg’s ravishing two-part The Souvenir, Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast. For Sorrentino, whose surreal flourishes, particularly the La Dolce Vita-esque The Great Beauty, have drawn Fellini comparisons, this is his Amarcord. (Fellini even makes a cameo here in a casting session scene.) But autobiographical doesn’t always feel like the natural mode for Sorrentino. As a master of decay and decadence, he has largely favored older characters (the politician of the propulsive Il Divo, the aged pals of Youth), and his orientation has been to make extravagant, stylish films of the world rather than of himself. That may be why The Hand of God is most vividly drawn when it’s looking around at Naples, at the Dickensian supporting characters.

Many scenes sparkle, like his father using a long pole to change channels on the TV. A remote, to him, is a sign of unwarranted excess. We’re communists, he says. We’re honest to the core. I liked The Hand of God most when the parents are central, in part because of just how good Servillo and Saponangelo are together, and because the film grows more wayward and disconnected once they’re gone.

But what interrupts the flow of The Hand of God also propels it into Fabietto’s coming of age and leads to his new ambition: to be a filmmaker. Little about this revelation, or any other in The Hand of God,” is completely clear. Sorrentino’s film is moving, in part, because it’s not totally reconciled to its memories he seems to be still working out the past. Though Fabietto has only seen a few films, like Once Upon a Time in America, he’s driven to make movies when grief leaves him searching for a purpose. Reality is lousy,” Fabietto says, quoting Fellini. His quandary recasts The Hand of God, and Sorrentino, himself, as a filmmaker seeking and storing wonderment where he can find it. His visual feasts are meals of sustenance to him, and maybe to us.

The Hand of God, a Netflix release, is rated R by the Motion Picture Association of America for sexual content, language, some graphic nudity and brief drug us. Running time: 130 minutes. Three stars out of four.

___

Follow AP Film Writer Jake Coyle on Twitter at: http://twitter.com/jakecoyleAP

Read all the Latest Movies News here

Comments

0 comment