views

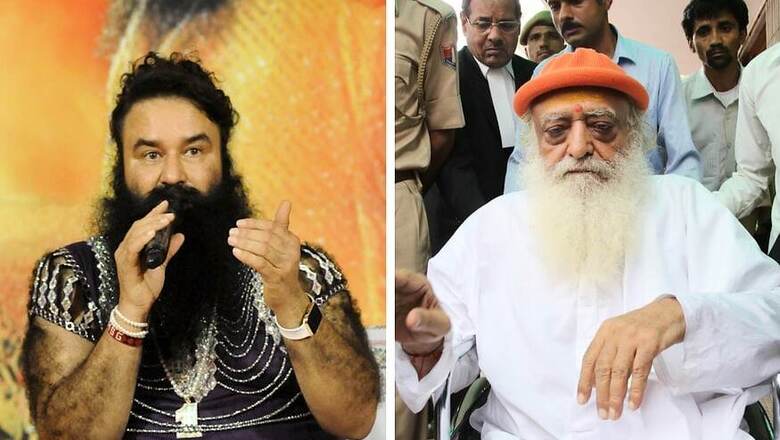

Murder, rape, castration, abduction — a rap sheet as long as his arm and yet Dera Sacha Sauda chief Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh Insan’s followers are ‘ready to die’ for him.

Many of those who sought to intimidate the state government and judiciary by converging in large numbers on Haryana’s Panchkula town in support of the ‘Love Charger’ guru, are well-educated, wealthy and socially prominent; certainly not wild-eyed fanatics.

The question of why mentally sound individuals are willing to sacrifice their health, wealth, family and friends at the behest of a godman continues to puzzle social psychologists. It is not that such people are chronically depressed or don’t value their lives; it is just that they value their guru more. In contrast with political or social activists, they are unconcerned with the social outcomes (constructive or destructive) of their actions. The guru is an end in himself.

Last year, Karnataka Congress MLC VS Ugrappa claimed he was viciously trolled by followers of Raghaveshwara Bharti, head of the Ramachandrapura Mutt, for denouncing police inaction in the sexual harassment cases against the godman.

In 2014, Jagat Guru Rampalji Maharaj’s refusal to surrender to the law led to a violent face-off between his followers and the Haryana police at his ashram in Barwala, resulting in the death of four women.

Likewise, Asaram Bapu, his son and Nithyanand Swami, jailed on charges of rape, continue to enjoy a substantial following.

Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh stands out among the herd of dubious godmen, not just because of his colourful personality, vast political network and success in evading the charges against him, but the blind dedication of his army of followers across all castes and classes.

Why would Hans Raj Chauhan submit to castration while in the prime of life, a surgery allegedly performed by doctors at the Dera? He claims (according to press reports) to have joined the cult at the age of 16, at the behest of his parents and quit only in 2009, after developing health complications following the surgery. In 2014, the Punjab and Haryana High Court handed over the probe into the alleged castration of 400 Dera Sacha Sauda followers to the CBI.

Nor did Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh’s followers suffer any diminution of faith when, in 2007, the CBI finalised three chargesheets against him, for the murders of former Dera manager Ranjit Singh and Sirsa-based journalist Ram Chander Chhatrapati and the sexual exploitation of female inmates. The latter was based on a probe ordered after an anonymous letter to then prime minister Atal Behari Vajpayee in 2002.

Yet another probe was ordered into the mysterious disappearance, in 1991, of Faqir Chand, an accountant at the Dera Sacha Sauda (the CBI tried to close the case in 2010, but it was revived by the High Court in 2016). An expose by a news magazine a decade ago alleged institutionalised sexual exploitation of ‘sadhvis’, forced castrations and a string of mysterious deaths.

Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh’s followers don’t buy it, maintaining that he is the victim of a conspiracy. But who would conspire against him? The Congress has sought his assistance in fighting Assembly elections, as have the BJP and the Akali Dal.

BJP general secretary Kailash Vijayvarghia famously called on the godman at his ‘Teravas’ in Sirsa, with an entourage of ministers and MLAs in tow, to thank him for his support in the Haryana assembly polls. State chief minister Manohar Lal Khattar returned the favour by giving the Dera a clean chit, after the High Court demanded that its premises be searched for illegal arms and ammunition.

The power of devotion is formidable: it creates suicide squads, enables a David to beat Goliath and mobilises a hundred thousand people to defy the law, bringing to a halt rail and communications networks! Ultimately, their devotion is based on a dependency syndrome. So central is the godman to the lives of his devotees, so essential to their identity and concept of self that they will ‘die’ for him. The devotee is more invested in the divinity of guru than the guru himself, because without it, his life lacks meaning.

Granted, most humans are vulnerable to the idea of a 'higher power'. Evolutionary psychologists trace this concept to the uniquely human ability for symbolic reasoning. The capacity for abstract thought enables humans to cooperate with genetic strangers in large numbers towards a cause bigger that they are, be it nation, community, religion — or a godman. (Women in particular are educated, through cultural symbols, to surrender their all to a higher cause.)

The dependency on the 'higher power' has been enhanced in the last few decades by abrupt socio-economic transformation. Community ties have weakened and society atomised, rendering the individual rootless and faceless. He or she finds a locus and an identity in the community of devotees around a godman.

The dissonance of modern life — where the individual either strives for wealth or, having found it, realizes that it does not bring happiness —drives people to seek a spiritual solution. The godman becomes their spiritual preceptor, psychologist, family confidante and business advisor. He holds out the promise of happiness, lays out a road map, takes away the burden of decision-making and invests life with purpose and meaning. And best of all, unlike an abstract deity or an idol, he is present in physical form. He can be seen, touched and heard.

The followers are thus open to brain-washing, or coercion through the threat of exclusion from the cosy community. At times, devotees may lose faith in the godman, when they perceive that he no longer has all the answers.

The Beatles abandoned Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, Mata Amritananmayee’s personal attendant fled from her, Sathya Sai Baba’s devotees accused him of sexually exploiting children. But such instances are the exception, not the norm.

Some analysts see the growing clout of spiritual entrepreneurs as a consequence of the increasing religiosity in Indian society. Meera Nanda, in The God Market, observes that “India is not free of the forces of politicised religiosity which expresses itself in a growing sense of Hindu majoritarianism”. Globalisation, she contends, has sharpened religious identities, fuelled by a state-temple-corporate nexus.

Perhaps that explains the success of Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh. The Dera Sacha Sauda was one of many cults in Punjab and Haryana when he took over in 1990. He expanded it many times over, leveraging his personal charisma and launching a variety of social welfare campaigns. His distinctly un-godmanlike behaviour – belting out rock songs and starring in home productions with sketchy social themes, high-end motorcycles and bizarre, bling costumes — is interpreted as reaching out to younger devotees. As the number of his followers has grown, so has his political clout — to the point where he now feels secure in challenging the secular power of the state.

(The writer is a senior journalist and author of Gurus: Stories of India's Leading Babas. Views are personal)

Comments

0 comment