views

Understanding the Types of Phonetic Sounds

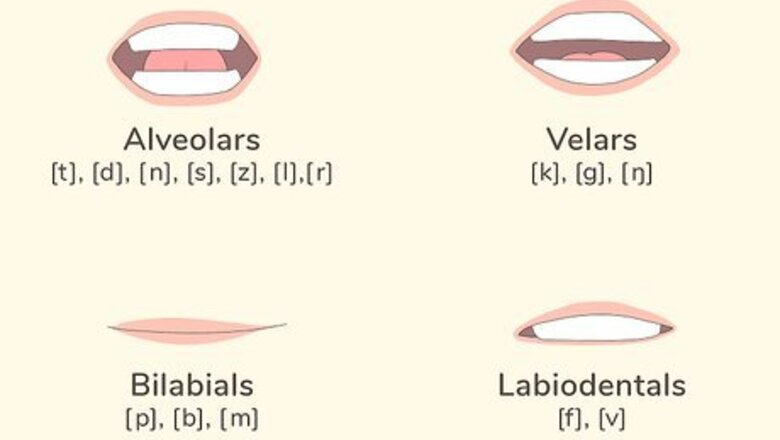

Learn how to classify consonants by place of articulation. Place of articulation refers to where in the mouth a consonant is produced. Typically, consonants are made by partially or completely blocking the flow of air at some point in the vocal tract, such as the lips, teeth, palate, or throat. Get familiar with major categories of consonants by place of articulation: Bilabials, such as [p], [b], and [m], are made by pressing the lips together. Labiodentals, like [f] and [v], are made by pressing the upper teeth to the lower lip. The interdentals, [θ] and [ð] (the unvoiced and voiced “th” sounds), are made by holding the tip of the tongue between the teeth. Alveolars are sounds made by placing the tongue on or near the roof of the mouth, just behind the teeth. These include [t], [d], [n], [s], [z], [l], and [r]. Palatals, which are not common in English, are made by raising the front part of the tongue to the palate. These include [ʃ], [ʒ], [ʧ], [ʤ], and [ʝ]. Velars are made by raising the back part of the tongue to the soft palate, toward the back of the mouth. These include [k], [g], and [ŋ] (the “ng” sound, as in “going”). Uvulars are made in the back of the throat by raising the back of the tongue to meet the uvula. These include [ʀ], [q], and [ɢ]. Glottals are made by modifying the flow of air in the glottis, inside your throat. These include [h] and the glottal stop, [Ɂ] (which you use in the middle of words like “uh-oh” or “nuh-uh”).

Familiarize yourself with the manners of articulation for consonants. The other way that consonants are categorized is by manner of articulation. This refers to the way you use the flow of air out of (or, in rare cases, into) your vocal tract to change the sound of the consonant. There are numerous manners of articulation, including: Voiced versus voiceless: This refers to whether the voice is used during the articulation of a consonant. For example, [f] is the voiceless counterpart to the voiced [v]. They are both labiodentals. Oral or nasal. This refers to the difference between consonants that are made with air moving through just the mouth (such as [p]) or also through the nose (like [n]). Stops, like [p], [b], [m], or [g], involve briefly blocking the flow of air through the vocal tract. Fricatives, like [f] and [v], require you to restrict the airflow enough to cause friction. Liquids, like [l] and [r], involve a slight obstruction of the airflow through the mouth that isn’t enough to cause any friction. Glides, like [j] (pronounced like “y” as in “yam”) and [w], involve very little restriction of air flow. Unless they’re at the end of a word, these sounds are always followed by a vowel. Some manners of articulation that are less common or nonexistent in English include trills and flaps (which are made by rapidly vibrating or tapping the tongue or lips against a point of articulation), as well as clicks (like the disapproving “tsk” sound you make with your tongue on the roof of your mouth).

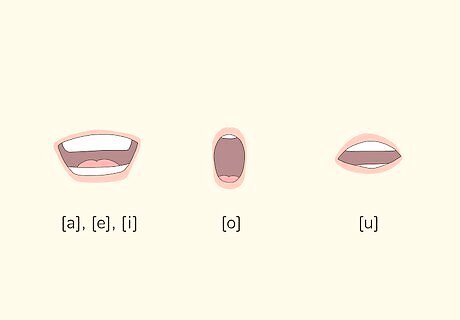

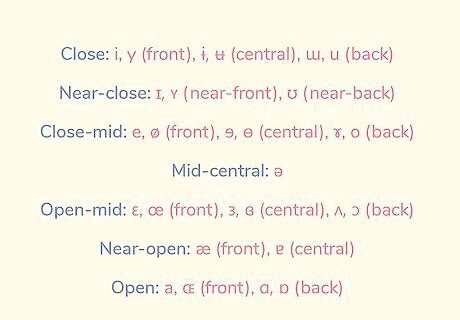

Get to know the placements of vowels in the mouth. Like consonants, vowels are also produced in various places in the mouth. Familiarize yourself with factors such as where the tongue is positioned, how open the jaw is, and how far back or forward in the mouth each vowel sound is created. For example, close vowels, like [i] and [u], are made with the jaw nearly closed and the tongue near the roof of the mouth. Open vowels, like [a] and [ɶ], are pronounced with the jaw open and the tongue lower in the mouth. There are also intermediate positions, such as close-mid, open-mid, and near-open. Vowels can also be pronounced in the front, central, or back part of the mouth. For example, [ɛ] (like the sound in “bread”) is a front vowel, while [ɑ] (as in “water”) is said in the back of the mouth. Vowels are typically described in terms of both positions—for example, “close central” or “mid back.”

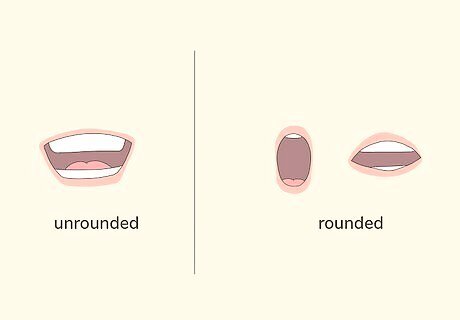

Distinguish between rounded and unrounded vowels. Rounded vowels are pronounced with the lips in a more rounded position, while unrounded vowels don’t require you to round your lips. Rounding is also used to organize vowels in phonetic writing. For example, rounded vowels are written to the right of unrounded vowels on an International Phonetic Alphabet chart, separated by a dot. Examples of rounded vowels in English include [o] (as in “boat”) and [u] (as in “boot”). While all English rounded vowels are pronounced toward the back of the mouth, other languages, such as French, have front-rounded vowels.

Study up on sounds that don’t exist in your language. Languages other than your own might have sounds that are completely unfamiliar to you, or that exist in your language only as non-speech sounds. Familiarize yourself with those sounds and their corresponding phonetic symbols so that you can recognize them and pronounce them correctly while reading phonetic writings in any language. For example, the front rounded vowel [ø] doesn’t exist in American English, but you’ll encounter it in numerous European languages.

Learning the International Phonetic Alphabet

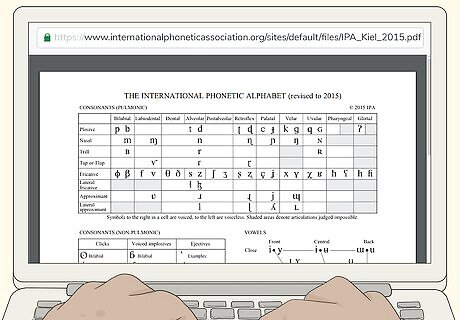

Download an IPA chart. You can find a helpful chart containing the entire International Phonetic Alphabet, along with special symbols such as diacritical marks and suprasegmentals, at the International Phonetic Association website. Download the chart and use it as a guide as you familiarize yourself with the IPA symbols.Tip: There are also a variety of helpful interactive IPA charts available, including an International Phonetic Association chart that features recordings and descriptions of each sound as well as font code information. The chart is divided up into pulmonic consonants, non-pulmonic consonants, and vowels, as well as other sounds and special symbols. The different sounds are organized according to place and manner of articulation. For example, you can find vowels by placement within the mouth (front, central, or back) as well as how closed or open the mouth is during articulation. Once you have the chart, you might find it helpful to make flashcards of the different symbols as a memorization aid. Put each symbol on the front and its name, description, and a helpful example word on the back.

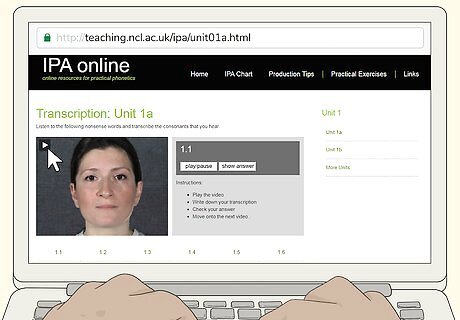

Use a pronunciation guide. As you are learning the different symbols in the International Phonetic Alphabet, listen to recordings of each sound so that you have a better idea of how they are pronounced. You can find a guide to the IPA with videos of speakers pronouncing the sounds here: https://teaching.ncl.ac.uk/ipa/index.html. This is especially helpful for learning to pronounce sounds that don’t exist in your native language. Practice saying the sounds out loud along with the guide, paying attention to the place and manner of articulation. This will help reinforce what you’re learning and make it easier for you to remember which sound each symbol represents.

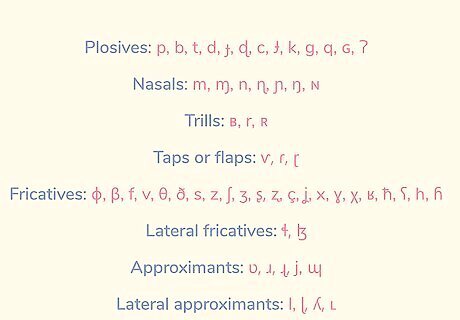

Learn the pulmonic consonants. Pulmonic consonants are the most common type of consonant sounds. In fact, English has only pulmonic consonants. These sounds are made by pushing air out from the lungs during speech. The IPA pulmonic consonants consist of: Plosives: p, b, t, d, ɟ, ɖ, c, Ɉ, k, g, q, ɢ, Ɂ Nasals: m, ɱ, n, ɳ, ɲ, ŋ, ɴ Trills: ʙ, r, ʀ Taps or flaps: ⱱ, ɾ, ɽ Fricatives: ɸ, β, f, v, θ, ð, s, z, ʃ, ʒ, ʂ, ʐ, ç, ʝ, x, ɣ, χ, ʁ, ħ, ʕ, h, ɦ Lateral fricatives: ɬ, ɮ Approximants: ʋ, ɹ, ɻ, j, ɰ Lateral approximants: l, ɭ, ʎ, ʟ

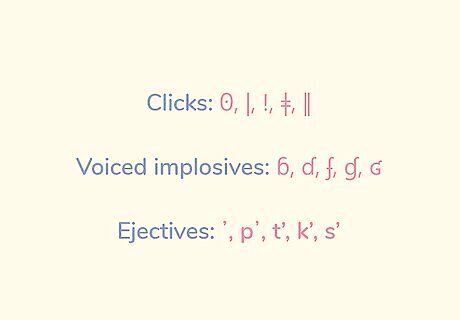

Get to know the non-pulmonic consonants. The non-pulmonic consonants are much less common than the pulmonic consonants, appearing in only a few languages. The airflow used to make non-pulmonic consonants is different from that used in pulmonic consonants—e.g., in some cases air is drawn in to make the sound, or it is pushed out through various parts of the vocal tract aside from the lungs. The non-pulmonic consonants include: Clicks: ʘ, ǀ, ǃ, ǂ, ǁ Voiced implosives: ɓ, ɗ, ʄ, ɠ, ʛ Ejectives: ʼ, pʼ, t’, k’, s’

Familiarize yourself with the vowels. The vowels in the IPA are organized by position within the mouth as well as how the mouth is shaped during pronunciation. Most of the vowels are paired into rounded and unrounded counterparts. The IPA vowels are as follows: Close: i, y (front), ɨ, ʉ (central), ɯ, u (back) Near-close: ɪ, ʏ (near-front), ʊ (near-back) Close-mid: e, ø (front), ɘ, ɵ (central), ɤ, o (back) Mid-central: ə Open-mid: ɛ, œ (front), ɜ, ɞ (central), ʌ, ɔ (back) Near-open: æ (front), ɐ (central) Open: a, ɶ (front), ɑ, ɒ (back)

Study the diacritics and other special symbols. In addition to consonants and vowels, the IPA contains a variety of symbols that do not fit neatly into those categories. These include phonetic sounds that don’t fit into any of the other categories of consonants or vowels, as well as symbols that indicate stress, tone, inflection, and variations in articulation. For example, a vowel that is nasalized would be written with the diacritical mark ̃ above it (e.g., [bĩn] for “bean”). Some modifiers help clarify other aspects of pronunciation, such as how long a syllable is held or whether it is stressed or not. For example, the symbol ˈ before a syllable indicates that it is the primary stress syllable, or the loudest syllable in the word.

Practice reading and writing words phonetically. Once you’ve spent some time getting familiar with the IPA, try putting it into practice. Make a list of vocabulary words written in IPA and try to sound out each word, paying attention to both the consonant and vowel symbols and other special symbols, like diacritics and suprasegmentals. You can also reinforce your knowledge further by writing out familiar words phonetically. For example, [ˌedʒʊ'keɪʃən] spells the word “education.” The suprasegmentals ˌ and ' show you which syllables receive the most stress (secondary and primary). The phonetic spelling also shows you the differences between the English spelling and how the word is actually pronounced (e.g., the “d” is actually a combination of 2 sounds, [d] and [ʒ]). You can also try phonetic matching games, like phonetic dominoes. Each card has a word written with its standard spelling on the top and a phonetic spelling of a different word on the bottom. Players try to match the phonetic spellings with the corresponding normal spelling of each word.

Comments

0 comment