views

Identifying Your Character's Motivation and Feelings

Put yourself in your character's shoes. This simple thought exercise is critical for identifying what your character is feeling, how those feeling might manifest themselves, and how to convey those to other characters in your work and to the reader. Empathy - the ability to understand another's feelings - is the crucial element in putting emotions into words. You need some idea of what your characters are doing, and why, in order to vividly describe them.

Decide what drives your characters. Knowing (or creating) a personality and story for your characters aids you in expressing their feelings. Do they seek revenge, or perhaps forgiveness? Are they relentlessly optimistic? This informs your word choices for the narrative of your story. To that effect, you can develop a backstory or character personality notes. Keep them handy on a separate page or a note card. The level of detail depends on how important the character is for your story. The protagonist will require more detail than a bit character. However, you should know each character's motivation and how they interact with each other, no matter how small the character. Character notes for a hard-bitten detective, for example, might include information like, “Orphaned at a young age, and has a soft spot for children.” “Resists emotional intimacy.” “Suffers, quietly, from PTSD.” “Skilled at hiding his fear while on the job.”

Outline your plot. Having at least some idea of how your story will progress and end enables you to attribute the right emotions, at the right times, to your characters. It isn't necessary to have every detail identified before you write, but plot twists and major events can have added emotional resonance if you can plan your character's emotional journey alongside their physical one.

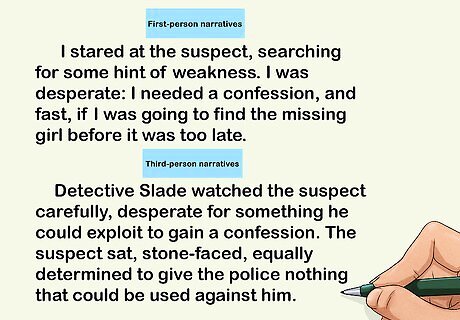

Decide on point of view. How you choose to present your story, generally in the first or third person, will dramatically affect what sort of perspective the reader has, and thereby, what emotions they can plausibly be aware of. First-person narratives, told by the main character, offer great opportunities for introspection on the narrator, but necessarily limits the reader's knowledge of other characters' thoughts and feelings to what the main character perceives. “I stared at the suspect, searching for some hint of weakness. I was desperate: I needed a confession, and fast, if I was going to find the missing girl before it was too late.” In this case, the narrator can only guess at what other characters are thinking and feeling. Third-person narratives offer more flexibility, and the reader can be made aware of as much, or as little, as you want them to know. You can choose if the reader only knows what the main character does, or you can expand it as far as you like. Just be consistent. “Detective Slade watched the suspect carefully, desperate for something he could exploit to gain a confession. The suspect sat, stone-faced, equally determined to give the police nothing that could be used against him.” In this example of third-person narration, the reader has “limited omniscience” - that is, they are aware to some extent of the thoughts and feelings of more than just the protagonist. Once you've chosen a point of view, develop the feelings and emotional state of the characters, focusing on what the reader will be aware of.

Finding the Words to Describe Feelings and Emotion

Consult a thesaurus. This helps you identify both synonyms, to avoid repetition, and antonyms, to provide contrast. Repeating the same few words can be off-putting for your readers, and more importantly, may not fully express the feelings you want to convey. Having access to a wide variety of vocabulary options gives you the flexibility to tell your story with style. Your character might be “happy,” “cheerful,” “optimistic,” “playful,” “effervescent,” or any number of synonyms. Antonyms - that is, the opposite of a word - are also useful for describing feeling. Look for ways to use indirect antonyms to expand your vocabulary. For example, the antonym of “happy” is “sad,” while an indirect antonym might be “depressed,” “blue,” or even a colloquialism like “down in the dumps.” Be sure to use a dictionary in conjunction with the thesaurus. You'll need to make sure the word fits the given meaning and context. It's usually best to avoid using the most elaborate word you can. Instead, choose one that's appropriate and matches your reader.

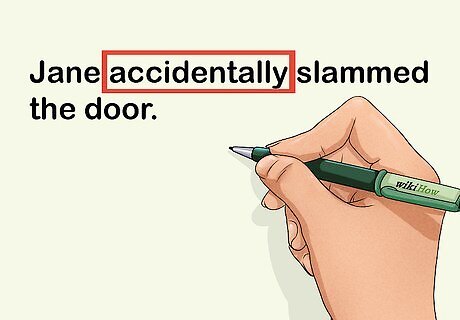

Use adverbs as well as adjectives. They provide crucial context and modification for what your character is doing, saying, or thinking. Adverbs - descriptors that modify verbs, usually ending in “-ly”, provide useful context for how your character does an action.“Jane slammed the door” leaves her motivation unclear. Adding an adverb clarifies things efficiently. “Jane accidentally slammed the door.”

Try a vocabulary list. If you're struggling with where to start, it can help you find a word that's close to what you want, and you can use a thesaurus to expand from there.

Using Action and Detail to Display Emotion

Show, don't tell. Bring your narrative to life by using action, character descriptions, and other context. Keep in mind that emotions and feelings are not the same thing. Emotions occur in the moment and are temporary, while feelings develop over time and are consistent. For example, anger is often an emotion, while hopelessness is usually a feeling. Your character's feelings and emotions will be emphasized by the context, rather than being clumsily pointed out. Don't tell the reader that “Sam was nervous.” Show them that “Sam paced back and forth in the waiting room, pausing only to wipe his brow. He looked up quickly each time the doors open, wondering each time if it would be the doctor with some news.”

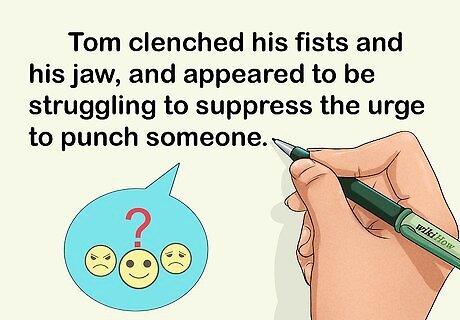

Use your characters' actions to illuminate their emotions. This can be a particularly effective way to demonstrate how a character feels, especially when writing in the first person, where the narrator is not aware of their thoughts. “Tom was angry” is far less convincing than “Tom clenched his fists and his jaw, and appeared to be struggling to suppress the urge to punch someone.”

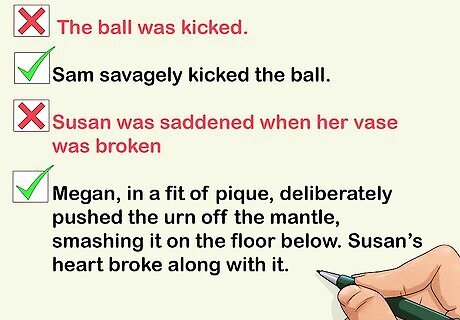

Avoid using the passive voice. Active language better expresses both actions and emotions. Passive voice constructions, built around “to be” verbs, often do not make the source of an action clear. Sometimes that can be useful, but generally active language makes for better reading. “The ball was kicked.” Who kicked the ball? Use active voice, with adverbs, to convey action and emotion. “Sam savagely kicked the ball.” “Susan was saddened when her vase was broken” leaves too much ambiguity. Instead, use active verbs. “Megan, in a fit of pique, deliberately pushed the urn off the mantle, smashing it on the floor below. Susan's heart broke along with it.”

Integrate body language. People show their emotions through expression, stance, and many other physical forms, so be sure to include that on the page. Describe things like facial expressions, perspiration, shaking or twitching, and posture. These often give physical form to emotions that are obvious in visual media, but require careful attention to convey in writing. You can make your own handy writing tool by creating a list of feelings and emotions. Then, list out the behaviors, gestures, and postures associated with those feelings and emotions. You can then use this as a cheat sheet. For example, you could show disgust with terms like “gag,” “flinched,” “grimaced,” or playfulness with terms like “nudge,” “wink,” or “waggle eyebrows.”

Comments

0 comment