views

X

Research source

Breeding ferrets, however, is not as simple as just pairing a male and female together. If you are thinking about your pet ferret, you will need to become very knowledgeable about the breeding process and spend the time (and money) to ensure the parents and babies are healthy.

Breeding Pet Ferrets

Select which ferrets to breed. Breeding ferrets is a serious responsibility. Breeding ferrets that are related or have behavioral and/or physical health problems could introduce undesirable traits into the ferret population. For example, breeding closely-related ferrets could result in health problems in the babies (e.g. blindness, deafness) or pregnancy-related problems for the mother (e.g., small litters, premature death of babies). If you already have a male and female ferret, you may want to have them genetically tested to make sure they are not closely related. Speak with your veterinarian about genetic testing options. Prior to breeding, take your ferrets to your veterinarian to ensure they are healthy.

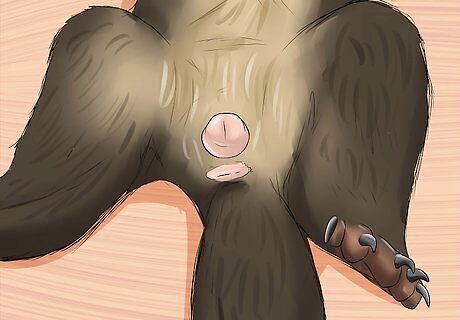

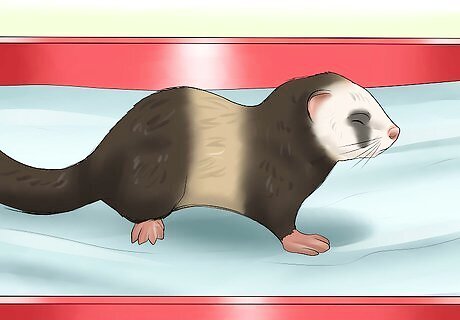

Watch for signs that the ferrets are ready to mate. Ferrets reach sexual maturity during the first spring after their birth. This will be about four months of age for females (‘jills’) and between six and eight months of age for males (‘hobs’). The spring coincides with the ferret breeding season, so start to look for signs that your ferrets are ready to breed when the days get longer and the temperature starts to warm up. A jill in heat will have a swollen and enlarged vulva, which is part of her external genitalia. You will notice a pink and watery secretion coming from her vaginal area. On your hob, you will notice that his testicles drop (hang lower from his body) and become larger. The hob equivalent of being in heat is a ‘rut.’ Your hob’s personal hygiene will take a nosedive when he’s ready to breed. He will urinate to mark his territory and even drag his stomach through the urine. He will also secrete oil to mark his territory. Male and female ferrets that are ready to breed both develop greasy skin and become quite smelly.

Place the jill in the hob’s cage. When you put the ferrets together, sit back and wait for the mating ritual to begin. Be aware that the ferret mating process is anything but romantic—the male will bite the female’s neck and even drag her around the cage. You may even hear the female scream. The biting will look disturbing, but it actually has a purpose—biting the jill’s neck releases the hormones in her body that will stimulate ovulation (egg production). Jills are known as induced ovulators, meaning that she has to be bred to start egg production. The mating process can take anywhere from several hours to several days, and occur over several sessions. The ferrets’ violent mating ritual may cause you to want to separate them. Don’t do this! The male ferret’s penis is curved such that it ‘locks’ the female in place until mating is over. Trying to separate them will do more harm than good.

Observe the jill after mating. After mating, move the jill back to her cage. If the mating was successful, she will gain weight and start nesting. She will also start pulling fur out of her tail and body. Jills also make clucking noises when they are pregnant. You can tell if the jill is pregnant starting about two weeks after a successful mating. You could also have your veterinarian perform an abdominal ultrasound on the jill, but this would be expensive. Jills can have phantom pregnancies, meaning that they act as if they are pregnant when they are not. High levels of hormones can cause your jill to become bloated and look as if she is pregnant. Keep in mind that your jill will need to eat more as she approaches the end of her pregnancy so she can handle the energy demands of giving birth and nursing. If the mating was unsuccessful, try again. Jills remain in heat unless they are bred, which can lead to serious health consequences, including pyometra (infected uterus),, bladder infections,, and anemia. Your female ferret must be bred or spayed if she is in heat.

Caring for the Pregnant Jill

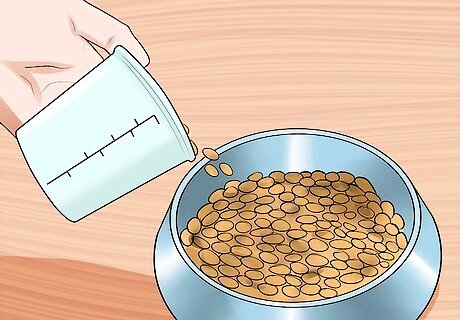

Increase your pregnant jill’s food intake. A jill’s pregnancy typically lasts about 42 days. Pregnancy and giving birth can take a toll on your pregnant jill’s health. She will need to take in more calories and protein to meet her increased energy demands. Feeding your jill more dry food will also give her the extra protein she will need during nursing. Feed her the highest quality ferret food that you can find to ensure she is in optimal health before giving birth. The diet for a pregnant jill should be at least 35% fat and 22% fat. To give her even more protein, supplement her diet with cooked meat (e.g., chicken) and liver. A pregnant jill that does not eat enough in late pregnancy can develop a very serious condition called pregnancy toxemia. This is an emergency situation—your veterinarian will need to perform a Cesarean section to save your ferret’s life.

Put more water in your pregnant jill’s cage. As with her food intake, your pregnant jill will need to drink a lot more fresh, clean water to get ready for birth and nursing. Increase her water intake to two to three times her normal intake. Put her water in a dish instead of a water bottle—she will likely drink more water from the dish. If she does not drink enough water, she will also not eat enough food. Without enough intake of food or water, your pregnant jill would not be able to produce enough milk for her babies.

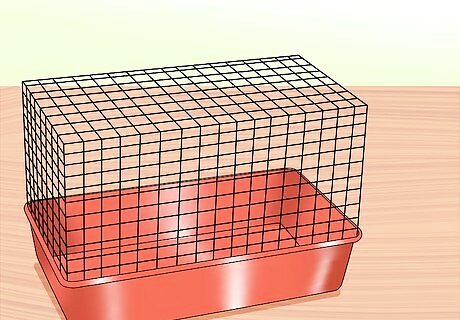

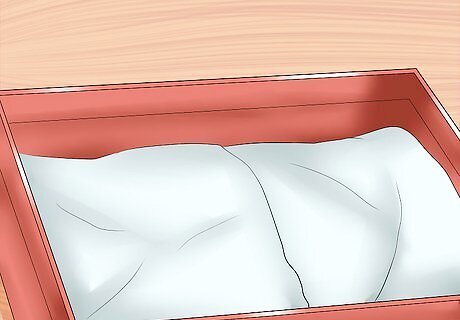

Prepare a separate cage for the pregnant jill. Your jill can stay with the hob through most of her pregnancy. About two weeks before the end of her pregnancy, you should move her to her own cage. Put fresh paper bedding or pine shavings in this cage. Your jill will use the bedding or shavings to make a nest. Place her cage in a warm, quiet part of your home so she can stay warm and prepare herself for giving birth. Ramp up her food and water intake when you move her to this separate cage.

Caring for the Jill After Birth

Give the jill her privacy. Jills are typically pregnant for about 42 days. When your jill gives birth, give her time alone with her babies (‘kits’) for at least a week. Jills may eat their kits when feeling scared or threatened—you definitely don’t want your jill to do this! You will need to feed her during this private time. Being as stealthy as you can, slip food and water in her cage when she is distracted. Jills can develop mastitis (mammary gland inflammation) and some of the kits may die after birth, so you should take a quick look at the mom and her babies when you put the food and water in the cage. Call your veterinarian if the jill doesn’t look well, or if you see dead kits that should be removed.

Feed your jill as you did when she was pregnant. Now that your jill is nursing, she will need just as much energy as when she was about to give birth. Continue to feed her two to three times her normal intake. Be mindful that if she has a large litter (more than 10 kits), she will lose weight no matter how much you feed her. With such a large litter, the caloric and energy demands will always outweigh how much she can eat.

Minimize bedding changes. Undoubtedly, your jill’s cage will become smelly after she gives birth. However, you should change the bedding only to check for neglected or abandoned kits. Just like when you put food and water in the cage, be stealthy when you change the bedding. If you have the cage in an enclosed room, the smell could become unbearable. Increase the air circulation in the room by keeping a door open.

Caring for the Kits

Handle the kits. When the kits are born, they are only two inches long and are completely dependent on their mother. Their eyes and ears are sealed shut, and they have only the slightest amount of pink fur on their bodies. You can start handling them when they are about one week old, keeping in mind their complete dependence on their mother. You may have to wait longer than a week if the jill doesn’t seem thrilled with you being near the cage as she cares for her babies. You don’t want your eagerness to handle the kits to be the reason she becomes scared and eats some of her babies. Because kits are so small when they are born, you can probably hold each one in one hand. As the kits get bigger, you would pick them up by gently grasping them between their neck and shoulders with one hand and supporting their hind legs with the other hand. Hold the kits for only a few seconds before placing them back in their cage. When the kits are about a month old, hold them for longer (a few minutes) and speak softly to them. Do not interrupt feeding time to hold the kits.

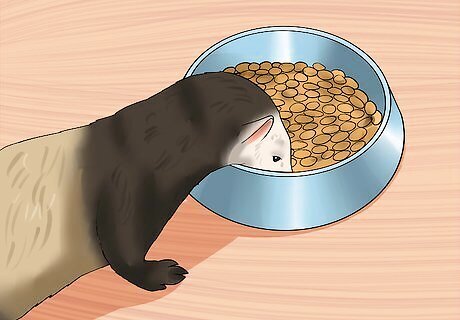

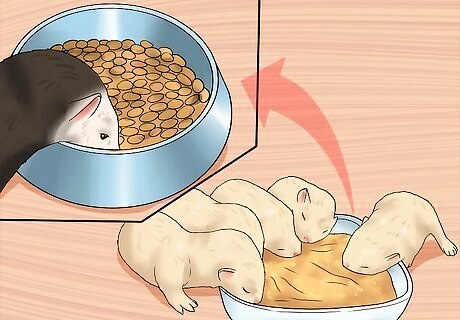

Feed the kits. Start introducing the kits to solid ferret food when they are about three weeks old. They will still be nursing at this point. They will also still have their baby teeth, so you should soak the solid food in water before feeding it to them. It may help to put the softened food in the refrigerator to let it soften a little more. You could try feeding the kits baby food as well. Ferrets can be picky eaters, so you may need to add some kitten milk replacer to the kibble to make it a little tastier. Check the label for the ferret food: it should be high in protein and low in carbohydrates. The protein source should be meat based, such as chicken. Cat foods are usually not ideal to feed ferrets, since they do not have enough fat to meet a ferret’s nutritional needs.

Wean the kits. The kits should be weaned they are about six weeks old. Their adult teeth will start growing in by this age, so you can start soaking their food in less and less water until you can feed them completely dry food. A kit will have its full set of adult teeth by about nine months of age. Keep in mind that kits should stay with their mother until 12 weeks of age. Although they will be able to eat solid food and should be more comfortable with human handling by six weeks of age, they should stay under their mother’s care for a little while longer.

Take the kits to the veterinarian. Your veterinarian should look over each kit to make sure it is healthy and growing well. The kits’ physical examinations will include checks for parasites, ear mites, fleas, and birth defects. Your veterinarian will make treatment recommendations based on the results of the physical examination. The kits will also need to receive several vaccinations: canine distemper vaccine at two and three months, and the rabies vaccine at three and four months.

Potty train the kits. Before you make the kits ready for adoption, you should train them in a few areas, such as potty training and training them not to bite. A simple way to potty train the kits is to watch first where they usually go to the bathroom. Place a litter box in that area and encourage them to use the litter box. It may help to give them a little treat each time they use it so they associate the litter box with something good. Ideal litters contain no dust. Examples include recycled paper pellets and fine softwood shavings. If the wood shavings contain cedar, the amount will likely be too small to cause toxicity in your kits. Clumping litter is not recommended because the kits can make a mess of it and possibly inhale it into their lungs.

Stop inappropriate biting behavior. Kits tend to explore their new world with their mouths, which means they will probably want to bite or nip at just about everything. The biting and nipping are also ways that kits establish hierarchy with their litter mates. To discourage inappropriate biting behavior, give the kit a firm ‘No!’ if it bites when you pick it up. It may take a long time for the kits to get the message that they’re not supposed to bite you, but they will eventually learn. Do not cuddle the kits until they learn not to bite. Discouraging a kit from biting at a young age will help them become better socialized by the time they are old enough to be adopted. Kits that are well trained and socialized will not bite and nip as much when they become adults. However, they will probably continue to nip at their toys and other cage items throughout their lives.

Comments

0 comment