views

Reading the Poem

Read through the poem a few times to get your first impression of it. Don’t stop to try to figure out what the poem might mean. Just read the entire poem a few times from start to finish and consider how it makes you feel. After you finish reading, answer the following questions in the margins or your notebook: What is the subject of this poem? Who might the speaker be? What could the poem mean? How do I feel after reading the poem? When might this poem take place? Did any significant images stand out? What?

Read the poem aloud to yourself, if you can. The way a poem sounds is important because it is very much an oral art form, so it’s best to read it aloud. You’ll more easily recognize the meter, rhyme scheme, and rhythm when you read aloud. Additionally, you’ll hear the effect of the way the poet arranged the words. You’ll likely need to read the poem aloud several times, especially when you start looking for sound devices later in your annotation. Look for a quiet location where you can read the poem. You may not be able to read the poem too loudly if you're taking a test or in a place where you can't talk, such as a library. If this is the case, read the poem quietly under your breath. This isn’t exactly the same, but it can help you if you’re trying to annotate the poem during a test or a similar situation.

Scan the poem to find its meter. Recognizing the meter will help you understand the poem’s form and structure. Read the poem aloud line by line. As you read, mark each unstressed (soft) syllable with a “u” and every stressed (hard) syllable with a “/”. If you notice a pattern of unstressed and stressed syllables, draw a line between each set of syllables to mark the feet of the poem. A metrical foot of a poem is a single set of syllables within a pattern of syllables in the poem. For example, if a line of poetry has a meter of “u/u/u/u/u/,” then a foot would be “u/.” A formal poem is likely to have a meter, while an informal poem may not. After you identify the number of feet, count the syllables in each line. Three feet is trimeter, 4 is tetrameter, 5 is pentameter, and so on. If you’re having trouble identifying the meter, try tapping a hand along as you read. Tap softly for unstressed syllables and harder for stressed syllables. Notice the pattern of the tapping. Keep in mind that this can take some practice, so be patient with yourself. You will encounter the iamb most often, which is 1 stressed and 1 unstressed syllable, but you will also encounter other patterns, such as the dactyl, trochee, anapest, pyrrhic, and spondee.

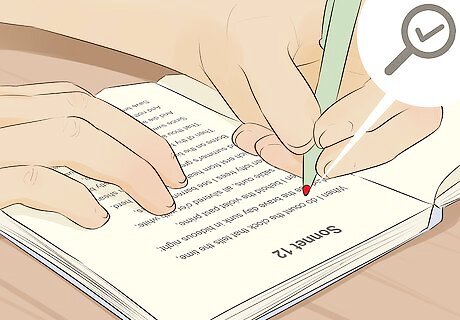

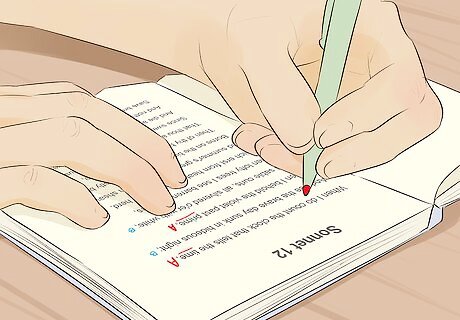

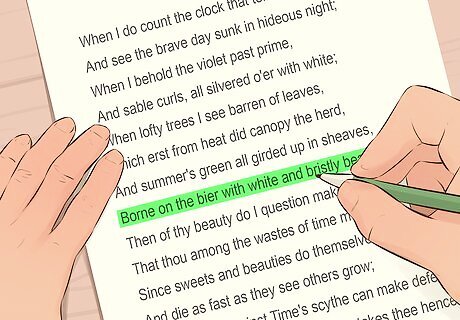

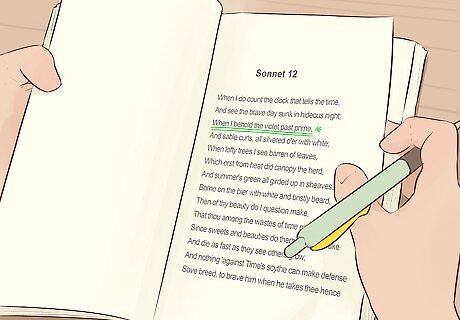

Determine the poem’s rhyme scheme, if it has one. The rhyme scheme will help you determine the poem’s form, as well as if the poem is formal or informal. To find the rhyme scheme, use letters to mark repeating rhymes. Start with an “A” on line 1, then use a new letter for a new sound or the same letter for a repeated sound. Continue until you finish marking the poem. Here's how you would label the rhyme scheme of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 12: When I do count the clock that tells the time, A And see the brave day sunk in hideous night; B When I behold the violet past prime, A And sable curls, all silvered o'er with white; B When lofty trees I see barren of leaves, C Which erst from heat did canopy the herd, D And summer's green all girded up in sheaves, C Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard, D Then of thy beauty do I question make, E That thou among the wastes of time must go, F Since sweets and beauties do themselves forsake E And die as fast as they see others grow; F And nothing 'against Time's scythe can make defense G Save breed, to brave him when he takes thee hence. G

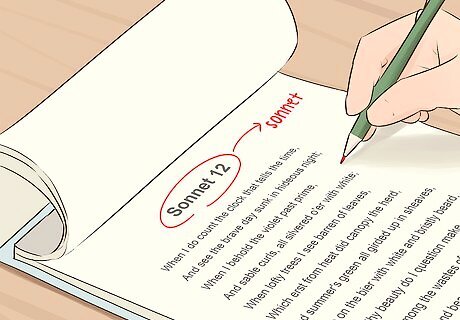

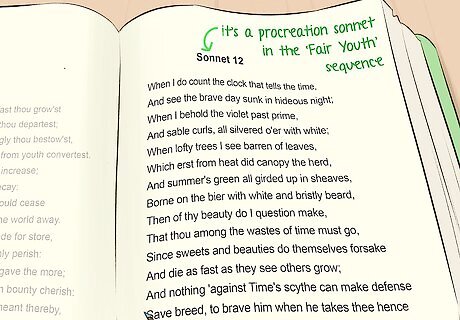

Identify the poem’s form, if it has one. A poem’s form can add to its meaning because it gives the poem structure. You can recognize form by looking at the rhyme scheme and meter of the poem and its stanza arrangement. Once you know the poem, consider why the poet may have chosen to use that structure for their poem. For example, the poem may be a sonnet, haiku, villanelle, acrostic, narrative, ballad, or blank verse poem. A poem that appears to have no form is called free verse. These are the most common forms used in poetry. A formal poem is more likely to adhere to a form, while an informal poem may not. An informal poem may loosely follow a form or may be free verse. If you’re having trouble figuring out which form the poem is, try searching the rhyme scheme on the Internet.

Highlighting Words and Phrases

Begin highlighting important or confusing lines on your second reading. Don't worry about highlighting everything important in one pass. Read the poem as many times as necessary to help you understand its meaning. Always read through the poem without stopping the first time. Then, start your annotation process on the second reading.

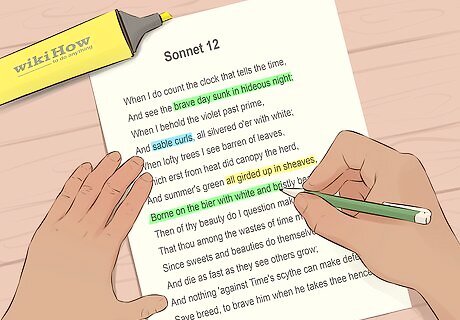

Use multiple colors of highlighters to organize your thoughts. Make each color represent a different piece of information. This will help you as you study the poem and write your notes. For example, yellow might represent passages you think are important, blue might identify words you don’t know, and pink could highlight passages you don’t understand. Use a system that works for you. If you only have one highlighter, that’s okay! Use it to identify passages you think are important or don’t understand.

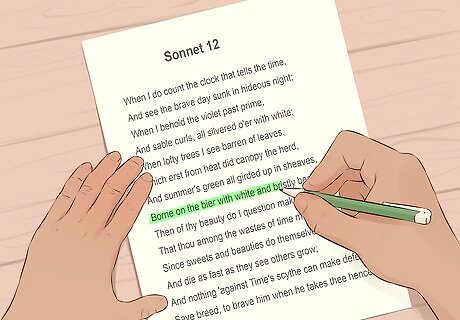

Highlight important passages so you can analyze them. Use your yellow highlighter to identify the key passages in the poem, such as repeated lines, imagery, or emphasized words and phrases. Mark any passage that seems significant to you. For example, you might highlight repeated words or lines. Also, identify what you have gleaned from the poem so far in your first readings and highlight anything that seems important or meaningful to you. Later, you can draw quotes from your highlighted passages, if you’re writing a paper on the poem.

Mark words you don’t know so you can look them up. Use a blue highlighter to indicate words that you either don’t know or don’t understand in the context of the poem. Then, look them up in your dictionary or online, depending on what’s available to you. If you know the word but aren't sure what it means in the context of the poem, analyze the sentence itself so you can use context clues to figure out what the poet means. If this doesn't help, you can use online resources to look at how people typically interpret that word in this particular poem. Keep in mind that poetry often uses words that have multiple meanings. Write out all of a word’s definitions if you are unfamiliar with them. This will aid you in your analysis. Don’t just skip over words you don’t know. The poet chose that word for a reason, so it’s important that you understand its meaning. It will help you more easily understand the poem’s overall meaning.

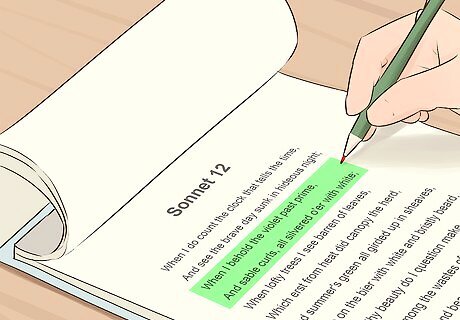

Highlight confusing lines so you can work out their meaning. Use your pink highlighter to mark lines that don’t quite make sense. For example, you might struggle to understand the line because of inverted syntax, a reference you don’t know, or a seeming contradiction. Highlight the line so you can spend more time on it. Inverted syntax means that the order of the words in a sentence is rearranged. For example, “Fruit blossomed on the tree” is normal syntax. Inverted syntax might read, “On the tree blossomed fruit.” It’s okay if you use two colors on the same line. For example, you might think a line is important but not understand it. In this case, you could mark it both yellow and pink. To keep the colors from bleeding together, highlight the top of the line in one color and the bottom of the line in another color.

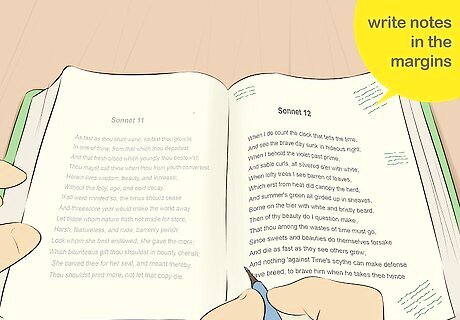

Writing Notes in the Margins

Begin writing notes on the poem on the second reading. After reading it for enjoyment the first time, start making notes on your paper. Add new notes each time you read the poem. Once you’ve highlighted your passages, go back through the poem and analyze the highlighted text in the margins.

Record your thoughts about the poem. Whenever you have a new thought or reaction, stop and write it down. At the end of each stanza, jot down a summary, your reaction, or any questions you have. As you read the poem, try to answer these questions for yourself. If you’re writing an essay about the poem, you can use these notes later to pull commentary for your analysis. If you can’t figure out the answer to one of your questions, talk to your instructor or a classmate. As another option, you might search for secondary sources online to help you better understand the poem.

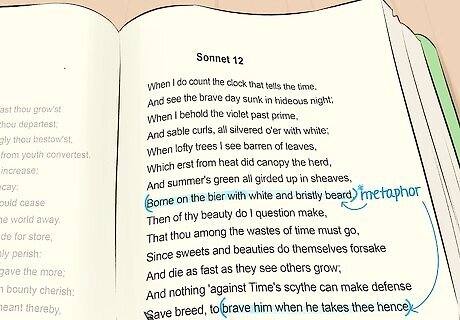

Identify literary devices used in the poem to understand the meaning. Poets use literary devices to convey meaning in poetry. Additionally, literary devices also enrich the poem, making it more interesting to the reader. Here are some common literary devices used in poetry: Figurative language includes descriptions and abstract images. For example, referring to a clock as a “pair of hands stealing hours” is figurative language. Symbols are objects, characters, situations, places, or words that have a meaning other than their literal meaning. For instance, the whale in Moby Dick is a symbol for nature, which can’t be conquered. Metaphor is the comparison between two seemingly unlike things, such as “her memory is a cup of sorrows.” Simile is the comparison of two seemingly unlike things but uses the words “like” or “as” to make the comparison. An example is “hot as the scorching sun.” Metonymy occurs when the poet refers to something using a word closely related to that thing. For example, they might refer to blood as “the lifeforce in your veins.” Synecdoche occurs when the poet uses part of something to stand for the entire person or object. They might write “The greybeards pondered,” instead of writing “The old men thought.” Hyperbole is an extreme exaggeration, such as “petals from a million roses.” Verbal irony is when someone says one thing but means another. A good example of irony is sarcasm, such as when you're having a bad day and say, "What a great day!"

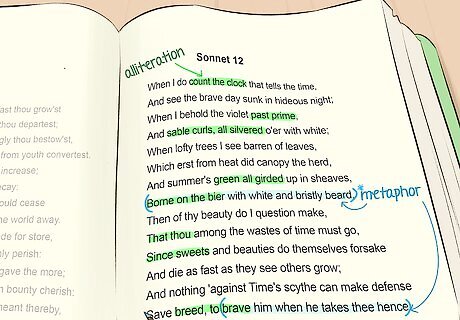

Recognize the sound devices used in the poem. Sound devices add richness and texture to the poem. Additionally, they allow the poet to more easily convey meaning. Look for these sound devices, which won’t be present in every poem: Alliteration is the repetition of the same letter sound in a line. For example, “Blackberries blooming on a prickly bush” is alliteration because of the repeating "b" sound. Assonance is the repetition of a vowel sound within a line or lines. As an example, “Sweet tea flowed free” has a repeating “e” sound. Consonance is the repetition of a consonant sound within a line or lines. For instance, “Tickets sold, I kicked the lock” has a repeating “k” sound. Rhythm is the pattern of the sound, which is created by the meter. Onomatopoeia are sound words, such as “bam” and “pow.” Off rhyme occurs when two words nearly rhyme but not quite. For instance, “off” and “loft” almost rhyme.

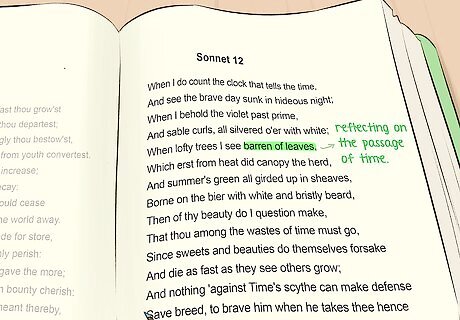

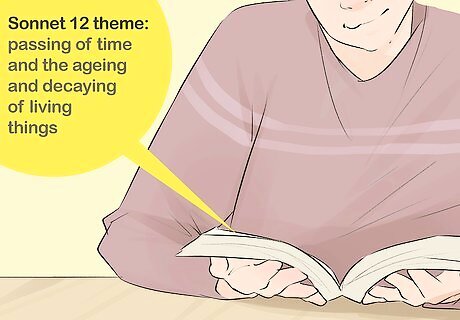

Examine the poem’s imagery to help you recognize the themes. Imagery evokes your senses so you can better enjoy the poem. It might trigger your sense of sight, sound, smell, touch, or taste. Note passages in the poem that contain words or phrases that help you experience the poem, then analyze what the poet might want you to take from them. Go through the poem and underline the descriptive words and phrases that trigger your 5 senses. For example, in Shakespeare’s Sonnet 12 above, we see barren trees that have lost their leaves and sable hair that has turned grey. This helps us understand that Shakespeare is reflecting on the passage of time.

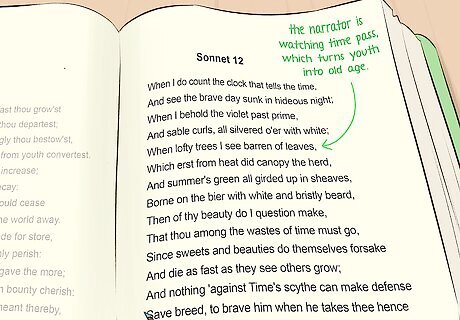

Summarize what’s happening in each stanza or section. It’s very hard to summarize a poem, but making brief summaries for yourself can help you figure out the poem’s meaning. Jot down what you think each passage is talking about, and identify any notable images in that passage. Later, this can help you analyze the poem. For example, we might summarize the first four lines of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 12 like this: “The narrator is watching time pass, which turns youth into old age.”

Analyzing the Poem

Identify the speaker of the poem. The speaker in the poem is the narrator. If you think the speaker is the poet, consider their persona. What is their perspective? What do they seem to think or feel according to their words? However, remember that the poet as the speaker isn’t always the case. It’s important to know who the speaker is to help yourself understand the poem. Here are some questions to ask yourself: Could the speaker be the poet? Does the speaker provide their name? Does the image of the speaker match your image of the poet? What does the language used in the poem tell me about the speaker? What does the speaker’s attitude suggest about the speaker? What is the setting? What is the situation in the poem? How might I describe this speaker?

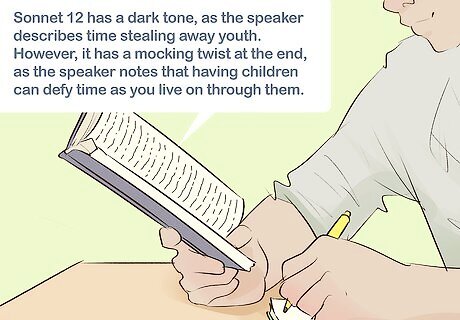

Determine the tone of the poem. The tone is the mood or attitude of the speaker toward the subject. It can help you understand the messages within the poem, as the tone shows what the poet wants you to feel about the subject. Consider how the poem made you feel, as well the language used in the poem. For example, Shakespeare’s Sonnet 12 has a dark tone, as the speaker describes time stealing away youth. However, it has a mocking twist at the end, as the speaker notes that having children can defy time as you live on through them.

Focus on the sentences in the poem rather than the line breaks. While line breaks are important to the structure of the poem, the poet still expresses their thoughts in sentences. Read through the line breaks and stop at punctuation when you’re studying the poem’s meaning. Notice if the lines use enjambment or end-stopped lines. Enjambment means that thoughts continue across multiple lines or couplets, while end-stopped lines end with punctuation. After you have gotten a sense of where the lines break, think about why the poet may have arranged their words in this way. For example, does this arrangement place more emphasis on certain words? If the poem lacks punctuation, stop at the line breaks. However, consider if the poet didn't use punctuation because they intended for you to stop at the line breaks, or if the poet didn't use punctuation because the thought continues to the next line.

Find the setting of the poem. The setting of the poem is when and where the poem takes place. This can help you understand the context of the poem. You can determine the setting using the descriptions in the poem. If it’s not clear where the poem is set, the historical and cultural context of the poem may help you understand it. You can determine the historical and cultural context of a poem by examining the language the poet uses, the situation the poem presents, and the background of the poet. It's also helpful to read about the era when the poet wrote the poem. Although historical and cultural context are important, don’t make them the focus of your interpretation of the poem.

Determine the poem’s themes to understand its meaning. The themes are the underlying messages or major ideas expressed in the poem, such as love and loss. The poem will have one or more themes that the poet is trying to get across. These themes will be the heart of the poem’s meaning. Here are some questions to help you find the themes: What is the speaker’s attitude toward the subject? What does the imagery suggest about the subject? What events happen in the poem? What does the setting look like? How does the poem make me feel? Why might the poet have written this poem? Who is the poem directed toward?

Decide what the title tells you about the meaning of the poem. Poem titles may add to the meaning of the poem. For example, some poets may choose a title to tell you what they were thinking about when they wrote the poem. However, some poems may be untitled or take their title from the poem itself. For example, Shakespeare’s Sonnet 12 takes its title from its number in the sequence of poems. The title doesn’t tell you anything new about the poem. However, if the title were “When I Look Upon My Love,” you would know the occasion of the poem, which could help you understand the meaning in more detail.

Comments

0 comment